ARCTIC TRIBES

Ethnographers commonly classify indigenous peoples in the United States and Canada into ten geographical regions with shared cultural traits (called cultural areas).

The following list groups peoples by the Arctic region.

The Arctic culture area is a cold, flat, treeless region (actually a frozen desert) near the Arctic Circle in present-day Alaska, Canada and Greenland.

It is home to the Inuit and the Aleut. The Inuit and Aleut groups speak dialects descended from what scholars call the Eskimo-Aleut language family.

Because it is such an inhospitable landscape, the Arctic’s population was and is comparatively small and scattered.

Some of its peoples, especially the Inuit in the northern part of the region, were nomads, following seals, polar bears and other game as they migrated across the tundra.

Some of its peoples, especially the Inuit in the northern part of the region, were nomads, following seals, polar bears and other game as they migrated across the tundra.

In the southern part of the region, the Aleut were a bit more settled, living in small fishing villages along the shore.

This section provides general information for collective groupings of tribes, bands, and villages who share cultural traits and live in the Arctic geographical region.

See Alaskan Natives A to Z for information specific to individual federally recognized tribes or villages in Alaska, which may not apply to all tribes who share their culture group.

Location:Alaska, parts of Canada, eastern Siberia (Russia), and Greenland

Also see: Villages by Region

The Arctic Region

The Arctic Culture Area spreads across northern North America and is an area which can be described as a cold desert.

It is a region which lies above the northernmost limit of tree growth. The area has long, cold winters and short summers. Everything freezes for 9 to 10 months of the year.

Cold, icy winters have below freezing temperatures and small amounts of daylight.

During the summer, the tundra becomes boggy and difficult to cross, and has long periods of daylight, up to 20 hours a day.

The Arctic Region runs across modern northern Canada and the two oceans from modern Siberia to Greenland (5000 miles long). It includes 3 oceans and the Arctic circle.

Paleo-Eskimo, prehistoric cultures, Russia, Alaska, Canada, Greenland, 2500 BCE–1500 CE

Arctic small tool tradition, prehistoric culture, 2500 BCE, Bering Strait

Pre-Dorset, eastern Arctic, 2500–500 BCE

Saqqaq culture, Greenland, 2500–800 BCE)

Independence I, northeastern Canada and Greenland, 2400–1800 BCE

Independence II culture, northeastern Canada and Greenland, 800–1 BCE)

Groswater, Labrador and Nunavik, Canada

Dorset culture, 500 BCE–1500 CE, Alaska, Canada

Aleut (Unangan), Aleutian Islands of Alaska, and Kamchatka Krai, Russia

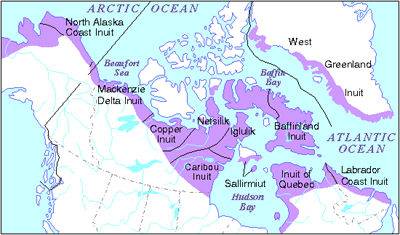

Inuit (Eskimo), Eastern Siberia (Russia), Alaska (United States), Canada, Greenland (Denmark)

- Thule, proto-Inuit, Alaska, Canada, Greenland, 900–1500 CE

- Birnirk culture, prehistoric Inuit culture, Alaska, 500 CE–900 CE

-

- Greenlandic Inuit people, Greenland

- Kalaallit, west Greenland

- Avanersuarmiut (Inughuit), north Greenland

- Tunumiit, east Greenland

- Inuvialuit, western Canadian Arctic

- Iñupiat, north and northwest Alaska

- Greenlandic Inuit people, Greenland

Yupik (Yup’ik and Cup’ik), Alaska and Russia

-

- Alutiiq people (Sugpiaq, Pacific Yupik), Alaska Peninsula, coastal and island areas of south central Alaska

- Central Alaskan Yup’ik people, west central Alaska

- Cup’ik, Hooper Bay and Chevak, Alaska

- Nunivak Cup’ig people (Cup’ig), Nunivak Island, Alaska

-

-

- Siberian Yupik people, Russian Far East and St. Lawrence Island, Alaska

- Chaplino

- Naukan

- Sirenik, Siberia

- Siberian Yupik people, Russian Far East and St. Lawrence Island, Alaska

-

Arctic | California | Northeast | Great Basin | Great Plains

NW Coast | Plateau | Southeast | Southwest | Sub Arctic

Subcategories

Article Index:

There are eleven linguistic groups of Athabascan Indians in Alaska. Athabascan people have traditionally lived along five major river ways: the Yukon, the Tanana, the Susitna, the Kuskokwim, and the Copper river drainages.

Athabascans migrated seasonally, traveling in small groups to fish, hunt and trap.

Today, Athabascans live throughout Alaska and the Lower 48, returning to their home territories to harvest traditional resources. The Athabascan people call themselves ‘Dena,’ or ‘the people.’

In traditional and contemporary practices Athabascans are taught respect for all living things. The most important part of Athabascan subsistence living is sharing.

All hunters are part of a kin-based network in which they are expected to follow traditional customs for sharing in the community.

The Athabascan Indians traditionally live in Interior Alaska, an expansive region that begins south of the Brooks Mountain Range and continues down to the Kenai Peninsula.

The area occupied by northern Athapaskan Indians lies directly south of the true arctic regions in a belt of coniferous forests broken in places by high mountains and stretches of treeless tundra.

Except in the far western portion where the Rocky Mountains occur, much of this area is of relatively slight elevation, and there are numerous low, rolling glaciated hills.

Climate of the Athapaskan Region

The climate of the region is is characterized by long, cold winters and short, warm summers. Snowfall is heavier than along the arctic coast, and in general the climate is quite different from the desert-like coastal areas inhabited by the Inuit and Inupiat.

House Types and Settlements

The Athabascans traditionally lived in small groups of 20 to 40 people that moved systematically through the resource territories. Annual summer fish camps for the entire family and winter villages served as base camps.

Depending on the season and regional resources, several traditional house types were used.

Athabascan Tools and Technology

Traditional tools and technology reflect the resources of the regions. Traditional tools were made of stone, antlers, wood, and bone.

Such tools were used to build houses, boats, snowshoes, clothing, and cooking utensils. Birch trees were used wherever they were found.

Athabascan Culture and Social Organization

The Athabascan culture is a matrilineal system in which children belong to the mother’s clan, rather than to the father’s clan, with the exception of the Holikachuk and the Deg Hit’an.

Clan elders made decisions concerning marriage, leadership, and trading customs. Often the core of the traditional culture was a woman and her brother, and their two families.

In such a combination the brother and his sister’s husband often became hunting partners for life. Sometimes these hunting partnerships started when a couple married.

Traditional Athabascan husbands were expected to live with the wife’s family during the first year, when the new husband would work for the family and go hunting with his brothers-in-law.

A central feature of traditional Athabascan life was (and still is for some) a system whereby the mother’s brother takes social responsibility for training and socializing his sister’s children so that the children grow up knowing their clan history and customs.

Athabascan Clothing

Traditional clothing reflects the local resources. For the most part, clothing was made of caribou and moose hide. Moose and caribou hide moccasins and boots were important parts of the wardrobe.

Styles of moccasins vary depending on conditions. Both men and women are adept at sewing, although women traditionally did most of skin sewing.

Athabaskan Transportation

Canoes were made of birch bark, moose hide, and cottonwood. All Athabascans used sleds –with and without dogs to pull them – snowshoes and dogs as pack animals.

Athabascan Regalia

Traditional regalia varies from region to region. Regalia may include men’s beaded jackets, dentalium shell necklaces (traditionally worn by chiefs), men and women’s beaded tunics and women’s beaded dancing boots.

Athabascan Traditions

Activities were marked by the passing moons, each named according to the changing conditions: “when the first king salmon comes,” “when the moose loose their antlers,” “little crust comes on snow,” and so on.

The winter was “the time we gathered together.” when scattered families returned to thier winter villages, hunted smaller animals close by and gathered for potlaches and other community celebrations.

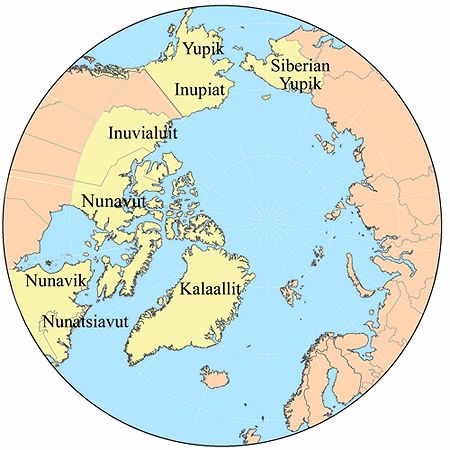

Eskimos are indigenous peoples who have traditionally inhabited the circumpolar region from eastern Siberia (Russia), across Alaska (United States), Canada, and Greenland. There are two main groups that are referred to as Eskimo: Yupik and Inuit. A third group, the Aleut, is related.

The Yupik language dialects and cultures in Alaska and eastern Siberia have evolved in place beginning with the original (pre-Dorset) Eskimo culture that developed in Alaska. Approximately 4,000 years ago the Unangam (also known as Aleut) culture became distinctly separate, and evolved into a non-Eskimo culture.

Approximately 1,500-2,000 years ago, apparently in Northwestern Alaska, two other distinct variations appeared. The Inuit language branch became distinct and in only several hundred years spread across northern Alaska, Canada and into Greenland. At about the same time, the technology of the Thule people developed in northwestern Alaska and very quickly spread over the entire area occupied by Eskimo people, though it was not necessarily adopted by all of them.

The earliest known Eskimo cultures (pre-Dorset) date to 5,000 years ago. They appear to have evolved in Alaska from people using the Arctic small tool tradition who probably had migrated to Alaska from Siberia at least 2,000 to 3,000 years earlier, though they might have been in Alaska as far back as 10,000 to 12,000 years or more. There are similar artifacts found in Siberia going back perhaps 18,000 years.

Today, the two main groups of Eskimos are the Inuit of northern Alaska, Canada and Greenland, and the Yupik of Central Alaska.

The Yupik comprises speakers of four distinct Yupik languages originated from the western Alaska, in South Central Alaska along the Gulf of Alaska coast, and the Russian Far East.

In Alaska, the term Eskimo is commonly used, because it includes both Yupik and Inupiat, while Inuit is not accepted as a collective term or even specifically used for Inupiat. No universal term other than Eskimo, inclusive of all Inuit and Yupik people, exists for the Inuit and Yupik peoples.

In Canada and Greenland, the term Eskimo has fallen out of favor, as it is sometimes considered pejorative and has been replaced by the term Inuit.

The Canadian Constitution Act of 1982, sections 25 and 35, recognized the Inuit as a distinctive group of aboriginal peoples in Canada.

Two principal competing etymologies have been proposed for the name “Eskimo”, both from the Innu-aimun (Montagnais) language. The most commonly accepted today appears to be the proposal of Ives Goddard at the Smithsonian Institution, who derives it from the Montagnais word meaning “snowshoe-netter”.

Jose Mailhot, a Quebec anthropologist who speaks Montagnais, however, published a paper in 1978 which suggested that the meaning is “people who speak a different language”.

The primary reason that Eskimo is considered derogatory is the arguable but widespread perception that in Algonkian languages it means “eaters of raw meat.” One Cree speaker suggested the original word that became corrupted to Eskimo might indeed have been askamiciw (which means “he eats it raw”), and the Inuit are referred to in some Cree texts as askipiw (which means “eats something raw”). The majority of academic linguists do not agree. Nevertheless, it is commonly felt in Canada and Greenland that the term Eskimo is pejorative.

The Inuit Circumpolar Conference meeting in Barrow, Alaska, officially adopted “Inuit” as a designation for all Eskimos, regardless of their local usages, in 1977. However, the Inuit Circumpolar Council, as it is known today, uses both “Inuit” and “Eskimo” in its official documents.

In Canada and Greenland the term Eskimo is widely held to be pejorative and has fallen out of favor, largely supplanted by the term Inuit.

However, while Inuit describes all of the Eskimo peoples in Canada and Greenland, that is not true in Alaska and Siberia. In Alaska the term Eskimo is commonly used, because it includes both Yupik and Inupiat, while Inuit is not accepted as a collective term or even specifically used for Inupiat (who technically are Inuit). No universal term other than Eskimo, inclusive of all Inuit and Yupik people, exists for the Inuit and Yupik peoples.

In 1977, the Inuit Circumpolar Conference meeting in Barrow, Alaska, officially adopted Inuit as a designation for all circumpolar native peoples, regardless of their local view on an appropriate term. As a result the Canadian government usage has replaced the (locally) defunct term Eskimo with Inuit (Inuk in singular). The preferred term in Canada’s Central Arctic is Inuinnaq, and in the eastern Canadian Arctic Inuit. The language is often called Inuktitut, though other local designations are also used.

The Inuit of Greenland refer to themselves as Greenlanders or, in their own language, Kalaallit, and to their language as Greenlandic or Kalaallisut.

Because of the linguistic, ethnic, and cultural differences between Yupik and Inuit peoples there is uncertainty as to the acceptance of any term encompassing all Yupik and Inuit people. There has been some movement to use Inuit, and the Inuit Circumpolar Council, representing a circumpolar population of 150,000 Inuit and Yupik people of Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and Siberia, in its charter defines Inuit for use within the ICC as including “the Inupiat, Yupik (Alaska), Inuit, Inuvialuit (Canada), Kalaallit (Greenland) and Yupik (Russia).” However, even the Inuit people in Alaska refer to themselves as Inupiat (the language is Inupiaq) and do not typically use the term Inuit. Thus, in Alaska, Eskimo is in common usage, and is the preferred term when speaking collectively of all Inupiat and Yupik people, or of all Inuit and Yupik people throughout the world.

Alaskans also use the term Alaska Native, which is inclusive of all Eskimo, Aleut and Indian people of Alaska, and is exclusive of Inuit or Yupik people originating outside the state.

The term Alaska Native has important legal usage in Alaska and the rest of the United States as a result of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971.

The term “Eskimo” is also used worldwide in linguistic or ethnographic works to denote the larger branch of Eskimo-Aleut languages, the smaller branch being Aleut.

Related Articles:

Eskimo / Esquimaux F.A.Q.

Are Eskimo and Inuit the same people?

Alaskan Native Cultures