Washington Indian Tribes

Many Native Americans lived in the Washington region when European explorers first visited the area. Some of these groups lived west of the Cascades.

The Chinook, Nisqually, Quinault, and Puyallup hunted deer and fished for salmon and clams. Others, the Cayuse, Colville, Spokane, and Nez Percé, lived east of the Cascades on the plains and valleys.

One of the best known of the Native Americans in this area was Chief Sealth, also known as Chief Seattle, who is believed to have born in central Puget Sound.

He is better known by the English pronunciation of his name, after which the largest city in Washington state was named. He was a chief of both the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes.

Chief Seattle was a member of the Suquamish people and welcomed the first European traders and settlers, eager to trade with them.

Unfortunately, Seattle’s efforts to work with Europeans made some of his own people suspicious, who plotted against him. Eventually, his people were defeated and Seattle died on a reservation.

WASHINGTON INDIAN TRIBES

FEDERALLY RECOGNIZED TRIBES

Federal list last updated 5/16

Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation

Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation (Colville, Chelan, Entiat, Methow, Okanogan, San Poil, Lake Nespelem, Nez Perce, Palouse, Moses, Sinkiuse, Wenatchee)

Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation

Hoh Indian Tribe of the Hoh Indian Reservation

Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe of Washington

Kalispel Indian Community of the Kalispel Reservation

Lower Elwha Tribal Community of the Lower Elwha Reservation

Lummi Tribe of the Lummi Reservation

Makah Indian Tribe of the Makah Indian Reservation

Muckleshoot Indian Tribe of the Muckleshoot Reservation

Nisqually Indian Tribe of the Nisqually Reservation

Nooksack Indian Tribe of Washington

Port Gamble Indian Community of the Port Gamble Reservation

Puyallup Tribe of the Puyallup Reservation

Quileute Tribe of the Quileute Reservation

Quinault Tribe of the Quinault Reservation

Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe of Washington

Shoalwater Bay Tribe of the Shoalwater Bay Indian Reservation(Chehalis, Chinook, Quinault)

Skokomish Indian Tribe of the Skokomish Reservation

Spokane Tribe of the Spokane Reservation

Squaxin Island Tribe of the Squaxin Island Reservation

Stillaguamish Tribe of Washington

Suquamish Indian Tribe of the Port Madison Reservation

Swinomish Indians of the Swinomish Reservation (Swinomish, Kikiallus, Lower Skagit, Samish)

Tulalip Tribes of the Tulalip Reservation(Snohomish, Snowqualmie, Skyhomish)

Upper Skagit Indian Tribe of Washington

STATE RECOGNIZED TRIBES

None – Washington State does not have state-recognized tribes, as some states do.

UNRECOGNIZED / PETITIONING TRIBES

The following tribes are landless, non-federally recognized. Some are categorized as non-profit corporations; some are pending federal recognition.

Chinook Indian Tribe of Oregon & Washington, Inc. (a.k.a. Chinook Nation)is located on Quinault reservation; the one petitioning is in Oregon. Letter of Intent to Petition 07/23/1979; Declined to acknowledge 7/12/2003, 67 FR 46204.(Washington and Oregon)

Duwamish Indian Tribe. Merged with Suquamish. Letter of Intent to Petition 06/07/1977; Declined to Acknowledge 5/8/2002, 66 FR 49966.

Kikiallus Indian Nation

Marietta Band of Nooksacks

Mitchell Bay Band

Noo-Wha-Ha Band

Snoqualamie Indian Tribe, part of Tualip reservation

Snohomish Tribe of Indians. Located in Washington, Snowhomish bands on Tualip reservation. Letter of Intent to Petition 03/13/1975; Declined to Acknowledge 03/05/2004.

Snoqualmoo Tribe of Whidbey Island. Letter of Intent to Petition 06/14/1988.

Steilacoom Tribe. Descendants of this tribe live on the Skokomish reservation. Letter of Intent to Petition 08/28/1974; Proposed Finding 2/7/2000

FIRST CONTACT TO PRESENT

The earliest European to meet any of the peoples of Washington was probably Juan de Fuca, a Greek navigator sailing under the Spanish flag, who, in 1592, visited the straits which now bear his name.

The names of the first European explorers to what is now the state of Washington are found in the names of many physical places in the Pacific Northwest. Inlets and bays bear the names Juan de Fuca (1592), Cook (1778), Puget (1791) and Gray (1792).

Two islands are named after Vancouver and Whidby (1791) while the largest rivers are named after Gray’s ship Columbia, and Lewis and Clark’s expedition of 1805.

The State of Washington was occupied by a great number of Indian tribes formerly very populous, particularly those along the coast. There are few traditions regarding migrations and those which we have apply almost entirely to the interior people.

After the Whites came it was unlikely that the Indians would move eastward in the face of the invasion and impossible for them to move westward.

The Makah way of life changed amost immediately upon European contact in 1788. Before non-Indian people came to Makah territory, Makahs lived in five villages that were occupied all year long (Neah Bay, Ozette, Biheda, Tsoo-yess, and Why-atch).

Temporary residences were at locations that attracted people seasonally. These places allowed Makahs to harvest and process special food resources, like spring halibut or summer salmon.

The Makah belonged to the Nootka branch of the Wakashan linguistic family.The Makah people now live on a reservation that sits on the most northwestern tip of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State.

The Cathlamet belonged to the Chinookan stock. The dialect to which they have given their name was spoken as far up the Columbia River as Ranier.

The Cathlapotle belonged to the Chinookan linguistic stock and were located on the lower part of Lewis River and the southeast side of the Columbia River, in what is now Clarke County.

The Cayuse were located about the heads of Wallawalla, Umatilla, and Grande Ronde Rivers, extending from the Blue Mountains to Deschutes River in Washington and Oregon.

The Chehalis belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family, being most intimately related to the Humptulips, Wynoochee, and Quinault.

The Chelan Indians were an interior Salish tribe speaking the Wenachee dialect.

The Chilluckittequaw lay along the north side of Columbia River, in the present Klickitat and Skamania Counties, from about 10 miles below the Dalles to the neighborhood of the Cascades. They may have been identical with the White Salmon or Hood River group of Indians and perhaps both. In the latter case we must suppose that they extended to the south side of the Columbia.

The Chimakum, the Quileute, and the Hoh together constituted the Chimakuan linguistic stock, which in turn was probably connected with the Salishan stock. They were located on the peninsula between Hood’s Canal and Port Townsend.

The Clallam (also spelled Nu-sklaim, S’Klallam, Tla’lem) were on the south side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, between Port Discovery and Hoko River. Later the Clallam occupied the Chimakum territory also and a small number lived on the lower end of Vancouver Island.

The Columbia or Sinkiuse-Columbia got their name because of their former prominent association with the Columbia River, where some of the most important bands had their homes. The Sinkiuse-Columbia belonged to the inland division of the Salishan linguistic stock, with their nearest relatives being the Wenatchee and Methow.

The Colville belonged to the inland division of the Salishan linguistic stock which included the Okanagon, Sanpoil, and Senijextee. They got their name from Fort Collville,a post of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Kettle Falls. They lived on the Colville River and that part of the Columbia between Kettle Falls and Hunters. See Colville Confederated Tribes.

The Copalis belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family located on the Copalis River and the Pacific Coast between the mouth of Joe Creek and Grays Harbor.

The Cowlitz belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family, yet shared some peculiarities with the inland tribes. Originally living along most of the lower and all the middle course of Cowlitz River, they were later divided between the Chehalis and Puyallup Reservations.

The Duwamish belonged to the Nisqually dialectic group of the coast division of the Salishan linguistic stock. They were closely related to the Suwamish tribe, and Chief Seattle was chief of both tribes in the mid 1800s.

The Hoh spoke the Quileute language and were often considered part of the same tribe, constituting one division of the Chimakuan linguistic stock and more remotely connected with the Salishan family. They lived on the Hoh River on the west coast of Washington.

The Humptulips belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic stock, being connected most closely with the Chehalis. They lived on the Humptulips River, and part of Grays Harbor, including also Hoquiam Creek and Whiskam River.

The Kalispel extended over into the eastern edge of the State from Idaho. (Washington, Idaho and Montana).

Klickitat is a Chinook term meaning “beyond” and having reference to the Cascade Mountains. The Klickitat belonged to the Shahaptian division of the Shapwailutan linguistic family.

The Chinook belonged to the Lower Chinook division of the Chinookan family. They were located on the north side of the Columbia River from its mouth to Grays Bay (not Grays Harbor), a distance of about 15 miles, and north along the seacoast to include Willapa or Shoalwater Bay.

The Kwaiailk belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family but a part of them were associated with the inland tribes by certain peculiarities of speech. Their nearest relatives seem to have been the Cowlitz and Chehalis.

The Kwalhioqua belonged to the Athapascan linguistic stock on the upper course of Willopah River, and the southern and western headwaters of the Chehalis.

The Methow located on the Methow River spoke a dialect belonging to the interior division of the Salishan linguistic stock. A detached band called Chilowhist wintered on the Okanogan River between Sand Point and Malott.

The Mical were a branch of the Shahaptian tribe called Pshwanwapam who lived on the upper course of Nisqually River.

The Nez Perce lived primarily in Oregon and Idaho, but occupied territory in the extreme southeastern part of Washington state. In later years, Chief Joseph, who was from the Wallowa Valley in Oregon, was sent to spend his final years on the Colville Reservation in Washington. His grave is alongside the highway that runs through Nespelem. (Washington, Idaho and Oregon).

The Nisqually gave their name to one dialectic division of the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic stock. They lived on the Nisqually River above its mouth and on the middle and upper courses of Puyallup River.

The Nooksack belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family. They separated from the Squawmish of British Columbia and speak the same dialect. (Washington and British Columbia, Canada).

The Palouse belonged to the Shahaptian division of the Shapwailutan linguistic stock, and were most closely connected with the Nez Perce. They lived in the valley of Palouse River in Washington and Idaho and on a small section of the Snake River, extending eastward to the camas grounds near Moscow, Idaho.

The Palouse are said to have separated from the Yakima. The Palouse were included in the Yakima treaty of 1855 but have never recognized the treaty obligations and have declined to lead a reservation life.

The Pshwanwapam belonged to the Shahaptian division of the Shapwailutan linguistic family, and probably were most closely connected with the Yakima.

The Puyallup tribe lived at the mouth of Puyallup River and the neighboring coast, including Carr Inlet and the southern part of Vashon Island. The Puyallup belonged to the Nisqually dialectic group of the Coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family.

The Queets (also known as the Quaitso) belonged to the Coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family and were most intimately related to their neighbors to the south, the Quinault.

Together with the Hoh and Chimakum, the Quileute constituted the Chimakuan linguistic family which is possibly more remotely related to Wakashan and Salishan. They are now on the Quileutc and Makah Reservations.

The Quinault belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family in the valley of the Quinault River and the Pacific coast between Raft River and Joe Creek. They were associated with a band called Calasthocle.

The Sahehwamish belonged to the Nisqually dialectic group of the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic stock. They have several sub-divisions.

The Samish on Samish Bay and Samish Island, Guemes Island, and the northwest portion of Fidalgo Island, belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family. The Samish were later placed on Lummi Reservation.

The Sanpoil belonged to the inland division of the Salishan linguistic stock, and were related most closely to its eastern section. Originally located on the Sanpoil River and Nespelem Creek and on the Columbia below Big Bend, they were later placed on the Sanpoil and Colville Reservations.

The Satsop belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family, and have usually been classed with the Lower Chehalis.

The Senijextee (also known as Lake Indians because they lived on Arrow Lake) belonged to the inland division of the Salishan linguistic stock, and were most closely connected with the Sanpoil.

The Senijextee lived on both sides of the Columbia River from Kettle Falls to the Canadian boundary, the valley of Kettle River, Kootenay River from its mouth to the first falls, and in the region of the Arrow Lakes, B. C. The Lake Indians on the American side were placed on Colville Reservation.

The Sinkaietk are sometimes classed with the Okanagon, and called Lower Okanagon, both constituting a dialectic group of interior Salishan Indians. They lived on the Okanagan River from its mouth nearly to the mouth of the Similkameen.

Subdivisions included the Kartar, from the foot of Lake Omak to the Columbia River; the Konkonelp, who had winter sites from about 3 miles above Malott to the turn of the Okanagan River at Omak; the Tonasket, from Riverside upstream to Tonasket; and the Tukoratum, who had winter sites from Condon’s Ferry on the Columbia to the mouth of the Okanagan River and up to about 4 miles above Monse, Washington.

The Sinkakaius belonged to the interior division of the Salishan linguistic stock and were composed largely of people from the Tukoratum Band of Sinkaietk and the Moses Columbia people.

They lived between the Columbia River and the Grand Coulee extending up to Waterville.

The Skagit lived on the Skagit and Stillaguamish Rivers (except about their mouths), and belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic stock. There are numerous sub-divisions.

The Skilloot lived on both sides of Columbia River above and below the mouth of Cowlitz River, and belonged to the Clackamas dialectic division of the Chinookan linguistic family. (Washington and Oregon).

The Snohomish on the lower course of Snohomish River and on the southern end of Whidbey Island belonged to the Nisqually dialectic group of the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic stock. Subdivisions included the Sdugwadskabsh, Skwilsi’diabsh, Snohomish, and Tukwetlbabsh.

The Snoqualmie on the Snoqualmie and Skykomish Rivers belonged to the Nisqually branch of the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family.

Subdivisions include the Snoqualmie, Skykomish, and Stakta’ledjabsh.

The Spokan (now spelled Spokane), belonged to the inland division of the Salishan linguistic stock, and were most closely connected with the Kalispel, Pend d’Oreilles, Sematuse, and Salish. They lived near the falls on the the Spokane and Little Spokane Rivers, southward to, and perhaps including, Cow Creek, and northward to include all of the northern feeders of the Spokane. They were given a reservation at Ford, Washington.

The famous contemporary poet, Sherman Alexie, is from this tribe. Subdivisions of the Spokan include the Lower Spokan (about the mouth and on the lower part of Spokane River, including the present Spokane Indian Reservation), the Upper Spokan or Little Spokan (occupying the valley of the Little Spokane River and all the country east of the lower Spokane to within the borders of Idaho), the South or Middle Spokan (occupying at least the lower part of Hangmans Creek, extending south along the borders of the Skitswish).

The Lower and most of the Middle Spokan, and part of the Upper Spokan, were finally placed under the Colville Agency; the rest are on the Flathead Reservation in Montana and the Spokane Indian Reservation in Washington.(Washington, Idaho and Montana)

The Squaxon on North Bay, Puget Sound, belonged to the Nisqually branch of the coast division of the Salishan linguistic family.

The Suquamish belonged to the Nisqually branch of the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic stock, their closest connections being with the Duwamish. The famous Chief Seattle (Sealth or Ts’ial-la-kum) was chief of both tribes.

The Swallah belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family on Waldron Island, Orcas Island, and San Juan Island.

The Swinomish belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic family, and are sometimes called a subdivision of the Skagit. They lived on the northern part of Whidbey Island and about the mouth of Skagit River. There were a number of sub-divisions or villages.

The Taidnapam on the headwaters of Cowlitz River, and perhaps extending over into the headwaters of the Lewis River, belonged to the Shahaptian division of the Shapwailutan linguistic family.

The Twana constituted one dialectic group of the coastal division of the Salishan stock on both sides of Hood Canal. There were a number of sub-divisions and villages. Later they were placed on Skokomish Reservation.

The Wanapam belonged to the Shahaptian division of the Shapwailutan linguistic stock and were connected closely with the Palouse. They lived in the bend of Columbia River between Priest Rapids and a point some distance below the mouth of Umatilla River, and extending east of the Columbia north of Pasco. There were two branches, the Chamnapum and Wanapam proper.

The Watlala occupied the north side of Columbia River from the Cascades to Skamania and perhaps to Cape Horn, and also a larger territory on the south side in Oregon.

The Wauyukma on the Snake River below the mouth of the Palouse belonged to the Shahaptian division of the Shapwailutan linguistic family and were very closely related to the Palouse.

The Wenatchee belonged to the inland division of the Salishan linguistic family, their nearest relations being the Sinkiuse-Columbia Indians. Subdivisions included:

- Sinia’lkumuk, on the Columbia between Entiat Creek and Wenatchee River.

- Sinkumchi’muk, at the mouth of the Wenatchee.

- Sinpusko’isok, at the forks of the Wenatchee, where the town of Leavenworth now stands.

- Sintia’tkumuk, along Entiat Creek.

- Stske’tamihu, 6 miles down river from the present town of Wenatchee.

- Camiltpaw, on the east side of Columbia River.

- Shanwappom, on the headwaters of Cataract (Klickitat) and Tapteel Rivers.

- Siapkat, at a place of this name on the east bank of Columbia River, about Bishop Rock and Milk Creek, below Wenatchee River.

- Skaddal, originally on Cataract (Klickitat) River, on the west bank of Yakima River and later opposite the entrance to Selah Creek.

The Wenatchee are now under the Colville Agency.

The Wishram (also known as Wu’cxam, E-che-loot, and Ila’xluit) on the north side of Columbia River in Klickitat County belonged to the Chinookan stock, and spoke the same dialect as the Wasco. They had a number of villages.

The Wynoochee were closely connected with the Chehalis Indians and belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic stock.

The Yakama (also known as Cuts-sah-nem, Shanwappoms, Pa’ kiut`1ema, and Waptai’lmln) lived along the river of the same name and belonged to the Shahaptian division of the Shapwailutan linguistic family. Pa’ kiut`1ema (meaning “people of the gap”) and Waptai’lmln (meaning “people of the narrows”) are their own names for themselves.

Both of their names for themselves refer to the narrows in Yakima River at Union Gap where their chief village was formerly situated.

There are a number of sub-divisions and it is quite possible that under the term Yakama several distinct tribes were included.

The Yakama are mentioned by Lewis and Clark under the name of Cutsahnim, but it is not known how many and what bands were included under that term.

In 1855 the United States made a treaty with the Yakima and 13 other tribes of Shapwailutan, Salishan, and Chinookan stocks, by which these Indians ceded the territory from the Cascade Mountains to Palouse and Snake Rivers and from Lake Chelan to the Columbia.

The Yakima Reservation was established at the same time and upon it all the participating tribes and bands were to be confederated as the Yakama Nation under the leadership of Kamaiakan, a distinguished Yakama chief.

Before this treaty could be ratified, however, the Yakima War broke out, and it was not until 1859 that its provisions were carried into effect.

The Palouse and certain other tribes have never recognized the treaty or come on the reservation. Since the establishment of the reservation, the term Yakama has been generally used in a comprehensive sense to include all the tribes within its limits, so that it is now impossible to estimate the number of true Yakama.

PRE-CONTACT WASHINGTON TRIBES

The Clatskanie belonged to the Athapascan linguistic stock. The Clatskanie at one time owned the prairies bordering Chehalis River, Washington, at the mouth of Skookumchuck River, but on the failure of game, crossed the Columbia and occupied the mountains about Clatskanie River on the Oregon side of the river. For a long time they exacted toll of all who passed going up or down the Columbia.

The Neketemeuk were a Salishan tribe that lived above and near The Dalles in very early periods of contact.

The southern bands of the Ntlakyapamuk hunted in territory that is now in Washington.

The Semiahmoo belonged to the coastal division of the Salishan linguistic stock around Semiahmoo Bay in northwest Washington and southwest British Columbia. They have been absent from the Washington side since 1843. Only 38 remained on the Canada side in 1909.

The Wallawalla language belongs to the Shahaptian division of the Shapwailutan linguistic stock and is very closely related to the Nez Perce. They lived on the lower Wallawalla River, except perhaps for an area around Whitman occupied by Cayuse, and a short span along the Columbia and Snake Rivers near their junction, in Washington and Oregon. They are now on Umatilla Reservation, Oregon. (Washington and Oregon).

PRE-HISTORIC CULTURES IN WASHINGTON

40-17 million years ago – The Cascade Mountains are formed. The Olympic Mountains appear as islands in the Pacific.

17-6 million years ago – Floods of lava cover the Columbia Basin and destroy the Columbia River waterway.

6 million – 10,000 years ago – Washington’s Ice Age. Volcanos form in the Cascades and huge glaciers cover the mountains and Puget Sound. Floods shape the southern part of the state.

11,000 BP – People of the Clovis Culture inhabit the Northwest.

6,700 BP – Mount Mazama erupts

Between 12,000 and 16,000 years ago, scientists say a group of nomadic hunters crossed the frozen Bering Strait from Siberia into present-day Alaska and eventually moved further south into the Pacific Northwest.

Native american oral history says they were always there and the migration moved in the opposite direction, from the Pacific Northwest up into Alaska.

Although distinct communities developed over time, all of these native groups were dependent upon the land and the water for their livelihood. Most of their lives revolved around fishing, the smoking and drying of fish, and moving across the land in search of fish.

They lived in waterside villages of cedar plank houses. Another distinctive feature of these groups was their building of totem poles, which tell the stories of families, clans and individuals.

A 9,300 years old nearly complete skeleton found on the banks of the Columbia River on the Washington-Oregon border in 1996 was dubbed the Kennewick Man and battles between Indian tribes and scientists who want to study the skeleton have spawned lengthly court battles.

RESOURCES

Genealogy:Sources of records on US Indian tribes Washington Tribal Colleges

Article Index:

Ten years isn’t long. Not in a history that began 9,000 years ago. But the discovery of Kennewick Man on July 28, 1996, is dramatically reshaping beliefs about how humans populated the Americas. And his skeleton may continue to raise more questions about the past than it answers.

One of the most complete ancient skeletons ever found, Kennewick Man triggered a nine-year legal clash between scientists, the federal government and Native American tribes who claim Kennewick Man as their ancestor. And the long dispute has made him an international celebrity. Authors have pondered his mysteries in books, he’s been the subject of documentary films, his story is taught in classrooms across the globe, dozens of Web sites track his tale and his likeness recently appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ultimately ruled in the scientists’ favor, allowing the first studies of the bones last summer.

Some of the nation’s leading scientists began studying Kennewick Man about a year ago. They’ve released some of their findings but say future generations of scientists will be able to learn more from the ancient bones as technology advances.

The pioneer

When C. Loring Brace, 75, saw a picture of Kennewick Man’s skull accompanying a New York Times article in 1996, he instantly knew where his ancestors came from. “One look at that thing, and I knew it was going to relate to the Ainu of Japan,” he said. Brace, a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan, had to wait nearly nine years to study Kennewick Man.

He visited the bones for the first time last summer. He knew where Kennewick Man’s ancestors fit on the world map because he has carefully measured about 10,000 skeletons over nearly 30 years. He puts his complex measurements into a computer database, which allows him to study and track incremental change in human populations over time. Kennewick Man, and the handful of other ancient skeletons that have been found, are reshaping the way scientists view North American history. And the Bering Land Bridge theory now appears a little simplistic, they say.

It’s likely that waves of migrations came to North America, perhaps starting thousands of years before people first crossed the Bering Land Bridge.

“The Kennewick Man skeleton is a piece of all our histories,” said Thomas Stafford Jr., a Lafayette, Colo., geochemist. “Who’s the pioneer – the guy who came in a covered wagon, the American Indians that came 8,000 years ago or the people before them?” Brace said Kennewick Man supports the theory that ancient people traveled from Asia to North America by boat or on foot along coastlines and over ice sheets.

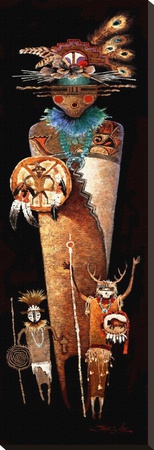

Buy Indian Story II See More Art by James Lee |

About 12,000 years ago, prehistoric hunters, called the Clovis people, followed big game animals across the land bridge between Siberia and Alaska. Modern Native Americans are likely their descendants. Brace said Kennewick Man is likely related to the ancient Jomon, who also were the ancestors of the Ainu people of Japan. The new theory is a radical shift in the long-accepted ancient history book. Brace said when he was finally able to measure Kennewick Man’s skull, his hunch proved right.

“I got my calipers on him, and it says what I expected it to,” he said. “Tying that across to Central Japan, that’s not something that most people in the business expected.” Kennewick Man might have been compared to a European when he was first discovered, because the Jomon people share similar characteristics, Brace explained. The Ainu don’t look like other Japanese, he said. They have light skin, wavy hair and body hair.

“Their eyes don’t look Asian at all,” Brace said. Not everyone agrees with this theory, Brace concedes, but then they don’t have his data. He said since populations were so much smaller 9,000 years ago, it’s very difficult to find skeletons because there weren’t established burial grounds or cemeteries.

And bones deteriorate over time with exposure to elements, so finding a complete skeleton from 9,000 years ago is even more rare. Stafford said Kennewick Man’s importance in reshaping theories about the past is “extraordinary.” “There are so few of these skeletons that every single one of them is priceless,” he said. “To lose one out of six is just inconceivable.”

The ancestor

That view clashes with Mid-Columbia tribes, which haven’t given up hope of reburying the skeleton they call Ancient One. Only last month, tribal leaders prayed over Kennewick Man’s bones at the Burke Museum in Seattle. Last month, Audie Huber watched as the remains of 143 Native Americans were returned to the ground near Lyons Ferry State Park north of Washtucna.

They were dug up in the 1960s to make way for Ice Harbor Dam and had been stored in the anthropology departments of the University of Idaho in Moscow and Washington State University in Pullman. Huber, who works for the Umatilla Indian Reservation’s department of natural resources, helped orchestrate the return of the bones to the tribes under the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act or NAGPRA.

“The sense of relief was really palatable,” Huber said. “I lack the words to describe it.” Huber, a Native American from the Northwest coastal Quinault tribe, has been monitoring the Kennewick Man court case since the first hearing in 1996. The legal battle has been “exhausting,” he said. “But we are here to protect the resources and we will continue to do so.”

He said having remains sitting in boxes or on display in museums marginalizes living tribal members. Although the tribes have faced international criticism, their beliefs shouldn’t be hard to understand, Huber said. “Many cultures believe that once remains are in the ground, they should stay there,” he said.

Huber said the tribes are fighting for the right to be consulted on any studies of the bones through the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979, which protects archaeological sites and artifacts. The scientists say the tribes have no claim on the bones because the courts decided the tribes aren’t related to the ancient skeleton.

A bill introduced last year by Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., could expand the authority of NAGPRA and give tribes more control. “This amendment would bring all historical human remains under NAGPRA,” Huber said. Rob Roy Smith, the Seattle lawyer who represented the tribes in the Kennewick Man case, said if the new bill passed, it likely would not change anything in the Kennewick Man case.

The bill hasn’t gained much traction because the Iraq war and other concerns are taking precedent, Smith said. Huber said the tribes dedicated time and resources to the Kennewick Man case because they knew it would set a precedent for the federal government in future cases.

Smith hopes the tribes and scientists will have open discussions instead of long court cases if another set of remains is found on federal land. “There hasn’t been that next discovery to test what will happen under that statute,” Smith said. “But it’s just a matter of time. Hopefully we’ve learned our lessons.” Like the Mid-Columbia tribes, the Asatru Folk Assembly claimed Kennewick Man as an ancestor in late 1996.

Stephen McNallen, the religious leader of the Asatru, said he fought for about three years in court to have the skeleton studied because it might be linked to ancient Europeans. And he’s interested to see what studies of Kennewick Man’s DNA will reveal. The Asatru follow a pre-Christian European theology, with Viking gods such as Odin and Thor.

The group, founded in 1972, believes there were migrations of early Europeans to North America thousands of years before Columbus. “No matter who Kennewick Man turns out to be, it will be of great interest to everyone,” McNallen said. The Asatru gave up their fight in 2000 because the lengthy legal battle was requiring too much time and money, McNallen said.

And he said he wouldn’t have taken up the Kennewick Man issue so publicly if he’d known how much criticism the Asatru would face after performing religious ceremonies in the Tri-Cities. Minority religions are often misunderstood, he said. “I think it’s better to be more reserved than we were at that time,” he said. “We don’t invite outsiders and we don’t allow ourselves to be photographed (during religious ceremonies).”

If Kennewick Man proves to be related to another ethnic group, such as the Southeast Asians, the Asatru will readily accept the scientific evidence, McNallen said. “All we’ve wanted all along is just the facts,” he said.

The ‘window into the past’

The scientists who fought to study Kennewick Man for nine years said the wait was frustrating but allowed scientific methods and technology to improve. They say the bones are revealing stories of the past and raising even more questions.

“I’m kind of glad that some of the people in the government were so cautious,” said Stafford, the Colorado geochemist. “If we had studied it for a month and then reburied it, the things I’m telling you now wouldn’t exist.”

The experts who recently studied Kennewick Man say they are finishing their reports and will write a book or journal together. And they think their team effort will serve as an example of how to study future discoveries.

“To my knowledge, this is the first time (in North America) a study has been done with this many people,” Stafford said. In the past 10 years, Stafford has developed a more precise radiocarbon dating test that is accurate within 20 years. Previously, the best dating technology had a 500-year margin of error. He hopes to use his improved test on Kennewick Man’s bones. Several labs tested pieces of the bones for the government to determine the skeleton’s age, but the results varied by more than 2,600 years, Stafford said.

He is using leftover bone fragments and powders from those tests to determine what part of the bone might yield the most accurate radiocarbon date. The problem is finding the best protein for the test. As bone ages, bacteria, water and other elements break down the protein inside. Kennewick Man’s bones contain less than 1 percent to 5 percent of their original protein, Stafford said.

After thousands of years, the protein becomes harder to find and less consistent, like a badly mixed cake batter, he said. Stafford also wants to use chemistry to find out what Kennewick Man ate and where he might have traveled. The scientist plans to find out if Kennewick Man preferred vegetables, meat or fish.

“I am just amazed at all the new things I see in this skeleton,” he said.

“It gives me other ideas for other tests.” He hopes to complete his tests by September.

The scientists also want to try extracting DNA from Kennewick Man’s bones or teeth, although Stafford isn’t sure the technology is advanced enough to try yet. “We ought to let DNA technology catch up with our ideas,” he said. “We should do these experiments on bison bone and not on Kennewick.”

If successful, DNA testing could allow scientists to compare Kennewick Man’s genes with other populations around the world or tell scientists something about his physical traits. Hugh Berryman, research professor at Middle Tennessee State University, said Kennewick Man has just begun to tell his story.

Berryman, an anthropologist, does much of his work in forensics studying the recently dead. He’s an expert at interpreting skeletal injuries and figuring out how and why bones break. And after studying the ancient skeleton, he believes Kennewick Man was well loved.

Kennewick Man had healed from the spear wound in his hip, so he must have had close friends or family, Berryman said. “There were others that helped him survive,” he said.

“He wasn’t in good shape then.”

It’s unclear if Kennewick Man was injured while hunting, in battle or in a family dispute, Berryman said.

“Nine thousand years doesn’t make him any less a person,” he said.

“He had the same thoughts and feelings as we do. But I can safely say it was wasn’t a dispute over a parking space.”

Scientists plan to scan the spear point encased in hip bone to determine the stone’s origin. It may give some clue of how far Kennewick Man traveled or what peoples he may have encountered. Berryman said he and the other scientists have been able to understand much about Kennewick Man’s life, but future studies will undoubtedly find more answers and raise more questions.

“He is a window into the past,” Berryman said. “When you look at a skeleton like this, you are kind of communicating with him through technology. Fifty years from now, there may be some great technology and questions we can ask him.”

Here is a list of places to visit in Washington State USA to learn about Native American culture. Art centers, museums, Interpretive Centers, parks, and more.

Adam East Museum Art Center

122 W. Third

Moses Lake, WA 98837

mailing address:

PO Drawer 1579

Moses Lake, WA 98837

tel (509) 766-9395

fax (509) 766-9392

Alpowai Interpretive Center, Chief Timothy State Park

13766 Hwy. 12

Clarkstown, WA 99403

tel (509) 758-9580

Anacortes Museum

1305 8th St.

Anacortes, WA 98221

tel (360) 293-1915

fax (360) 293-1928