Native Authors->A-L

Native Authors->A-L

Article Index:

Anne Hillerman is Tony’s daughter and is an outstanding author in her own right, and the research she did shows in this police procedural featuring Chee, his wife, Bernadette Manuelito, Leaphorn and their fascinating family and friends.

Navajo Tribal cops Jim Chee and Bernadette Manuelito, and their mentor, the legendary Lieutenant Joe Leaphorn, investigate two perplexing cases.

The new book

The publication of Anne Hillerman’s “Rock with Wings” (Leaphorn and Chee Mysteries) is wonderful news for fans of Tony Hillerman’s (1925-2008) Navajo Police series featuring Jim Chee and Joe Leaphorn.

Doing a good deed for a relative who’s starting a tour bus service in Monument Valley offers the perfect opportunity for Sergeant Jim Chee and his wife, Officer Bernie Manuelito, to get away from the daily grind of police work. But two cases will call them back from their short vacation and separate them—one near Shiprock, and the other at iconic Monument Valley.

I was reminded of the 1988 Dirty Harry movie “The Dead Pool”, the last of the series featuring Clint Eastwood as SFPD Inspector Harry Callahan, which dealt with a movie production plagued by mysterious deaths, in the scenes in Monument Valley, where a motion picture is being filmed. Both movies are horror films.

Chee follows a series of seemingly random and cryptic clues that lead to a missing woman, a coldblooded thug, and a mysterious mound of dirt and rocks that could be a gravesite. Bernie has her hands full managing the fallout from a drug bust gone wrong, uncovering the origins of a fire in the middle of nowhere, and looking into an ambitious solar energy development with long-ranging consequences for Navajo land.

There’s more than enough action for a fan of the late, great Tony Hillerman in “Rock With Wings.” Leaphorn doesn’t play a major role in the novel, since he’s recovering from line-of-duty gunshot wounds, but his presence is felt by Bernie and Jim. Thanks, Anne, for continuing the outstanding series created by your dad, a decorated World War II veteran and a member of the Greatest Generation!

About the author

Anne Hillerman, daughter of best-selling mystery writer Tony Hillerman, continued her father’s Navajo detective series with “Spider Woman’s Daughter,” published Oct. 1, 2013 (HarperCollins.) The book follows the adventures of Joe Leaphorn, Jim Chee and Bernadette Manuelito as they track a would-be cop killer, travel to Chaco Canyon on the trail of a murderer, and discover intrigue in the world of ancient Indian art and artifacts.

She is the author eight non-fiction books including “Tony Hillerman’s Landscape: On the Road with Chee and Leaphorn.” She and photographer Don Strel made numerous road trips to photograph and write about the landscapes beloved by New Mexico’s best known mystery writer. Working on that book inspired her novel.

“In the process of researching Tony Hillerman’s Landscape, I re-read all of the Chee/Leaphorn mysteries, paying close attention to the settings. I ran into mud, dust storms, rez dogs, snow and those pricelessly beautiful days Tony Hillerman wrote about for more than 35 years,” Anne said. “I loved nearly every minute of it. My personal highlights included New Mexico’s Bisti badlands, the mysterious landscape near Ship Rock and vast, empty Chaco Canyon.”

Anne, the eldest of Tony and Marie Hillerman’s six children, came to New Mexico as a child and enjoys living in the Southwest. Her other major non-fiction projects include “Gardens of Santa Fe,” with features photos of Santa Fe’s finest gardens and interviews with their creators, and “Santa Fe Flavors: Best Restaurants and Recipes.”

Both received top honors at the New Mexico Book Awards. She worked for many years as a journalist, receiving awards for her writing from the New Mexico Press Association and the National Federation of Press Women. When she isn’t working, Anne likes to ski, garden and experiment with new recipes in the kitchen. She is a founder of the Tony Hillerman Writers Conference held annually in Santa Fe, N.M.

Ella Deloria, also known as Anpetu Wastewin, from anpetu “day,” waste “good,” win “woman,” was a Yankton Sioux scholar, interpreter, and lecturer who became a nationally famous linguist and ethnologist. She was born January 3, 1888 at Wakpala, South Dakota, the daughter of Reverend and Mrs. Philip Deloria (Tipi Sapa).

Zitkala-Ša, (“Red Bird”) 1876–1938 – Also known by the missionary-given name Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, was a Yankton Dakota Sioux writer, editor, musician, teacher and political activist.

Zitkala-Ša (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin) Biography

Zitkala-Ša was born to a Yankton Sioux mother and white father at the Yankton Sioux Agency in South Dakota on February 22, 1876. Missionaries later gave her the English name of Gertrude Simmons.

Her mother, Taté Iyòhiwin (Every Wind or Reaches for the Wind) was known by the English name Ellen Simmons. Her father was a European-American man named Felker, who abandoned the family while Zitkala-Ša was very young. Red Bird lived on the Yankton Reservation until she was 8 years old.

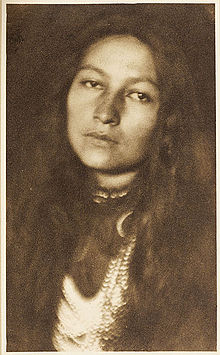

Photographed in1898 by Gertrude Kasebier.

In 1884, she attended White’s Manual Labor Institute school, a boarding school in Wabash, Indiana which was run by Quakers, for 3 years. She learned to read and write and play the violin during those years, which she later wrote about in her book, “The School Days of an Indian Girl.” Then she returned to the reservation to live with her mother for another three years. At that time, not wanting to become a housewife or housekeeper for a white family, the most common employment for Indian girls, ,she decided to return to the White’s Manual Labor Institute for more education.

In 1884, she attended White’s Manual Labor Institute school, a boarding school in Wabash, Indiana which was run by Quakers, for 3 years. She learned to read and write and play the violin during those years, which she later wrote about in her book, “The School Days of an Indian Girl.” Then she returned to the reservation to live with her mother for another three years. At that time, not wanting to become a housewife or housekeeper for a white family, the most common employment for Indian girls, ,she decided to return to the White’s Manual Labor Institute for more education.

This time she continued to study piano and violin, and started to teach music at White’s when the teacher resigned. In 1895 Zitkala-Sa was awarded her first diploma. She then decided to attend Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, where she had received a scholarship. Higher education for women was quite limited at the time. She also studied music at the Boston Conservatory.

During this time, she began gathering Native American legends, translating them first to Latin and then to English for children to read. In 1897, six weeks before graduation, she was forced to leave Earlham College due to ill health. She then found employment playing the violin with the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston from 1897 to 1899.

In 1899 she took a position at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where she taught music to the children and conducted debates on the treatment of Native Americans. In 1900 she played violin at the Paris Exposition with the school’s Carlisle Indian Band. In the same year she began writing articles on Native American life, which were published in such national periodicals as Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s Monthly.

In 1900, Carlisle’s founder, Colonel Richard Henry Pratt, sent her to the Yankton Reservation for the first time in several years to recruit students. She found her mother’s home in disrepair, her brother’s family had fallen into poverty, and white settlers were beginning to occupy lands allotted to the Yankton Dakota under the Dawes Act of 1877.

Upon returning to the Carlisle School, she came into conflict with its founder when she let him know that she resented his rigid program of assimilation into dominant white culture and the limitations of the curriculum, which prepared the children only for low-level work. That year she published an article in Harper’s Monthly describing the profound loss of identity felt by a Native American boy after undergoing the assimilationist education at the school and was fired.

Concerned with her mother’s advanced age and her family’s struggles with poverty, she returned to the Yankton Reservation, and soon got a job as a clerk for the Bureau of Indian Affiairs on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. While there, she began collecting more stories from Native Americans on the reservation to publish in Old Indian Legends.

In 1902 while working for the B.I.A., she met and married Captain Raymond Talefase Bonnin, who was 1/4 Yankton Sioux, and was raised in the Yankton culture. They had one son, Raymond Ohiya Bonnin.

Buy it at Amazon.com

After their marriage, Captain Bonnin was assigned to the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in Utah, where they lived for 14 years. She worked as a teacher for the Indian Service while they were there. This is where Zitkala-Ša met American professor and composer William F. Hanson. In 1910, they started their collaboration on the music for The Sun Dance Opera, for which Zitkala-Sa wrote the libretto and songs.

She based it on sacred Sioux ritual, which the federal government prohibited the Ute from performing on the reservation. She also played Sioux melodies on the violin, and Hanson used this as the basis of his music composition.

First Native American Opera

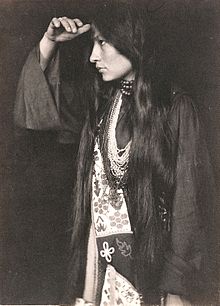

Zitkala-Sa, as photographed by

Joseph Keiley in 1901.

The opera premiered in Utah in 1913, with dancing and some parts performed by the Ute, while lead singing roles were filled by non-natives. It was the first opera ever to be co-authored by a Native American.

The opera premiered in Utah in 1913, with dancing and some parts performed by the Ute, while lead singing roles were filled by non-natives. It was the first opera ever to be co-authored by a Native American.

In 1938 the New York Light Opera Guild premiered The Sun Dance Opera at The Broadway Theatre as its opera of the year. It publicity credited only William F. Hanson as the composer.

Political Activism

Zitkala-Ša was highly politically active throughout most of her adult life.

In 1911 Red Bird became active in the Society of American Indians, an organization of educated Native Americans dedicated to the improvement of the conditions of their people. The group was basically interested in the integration and assimilation of the Indian, favoring equal rights for all people, and strongly opposed to the continuance of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

They were active in lobbying for the right to full American citizenship. Zitkala-Ša served as the SAI’s secretary beginning in 1916. She edited its journal American Indian Magazine from 1918 to 1919. Since the late 20th century, activists have criticized the SAI and Zitkala-Ša as misguided in their strong advocacy of citizenship and employment rights for Native Americans. Such critics believe that Native Americans have lost cultural identity as they have become more part of mainstream American society.

As the secretary for the SAI, Zitkala-Ša corresponded on its behalf with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She began to criticize the practices of the BIA, such as their attempt to prohibit Native American children from using their native languages and cultural practices at the national boarding schools. She reported incidents of abuse resulting from children’s refusal to pray in the Christian manner.

Her husband was dismissed from his BIA office at the Ute reservation in 1916. The couple and their son relocated to Washington D.C, where they thought to find allies. Zitkala-sa was the society’s secretary when the Bonnins moved to Washington, D.C. She lobbied for her people among the various officials in the Capitol, and also helped persuade the General Federation of Women’s Clubs to take an active interest in Indian welfare. Roberta Campbell Lawson, a part-Delaware woman from Oklahoma was also prominent in the club’s hierarchy at this time, and the two women worked together closely.

From Washington, Zitkala-Ša began lecturing nation-wide on behalf of the SAI to promote the cultural and tribal identity of Native Americans. During the 1920s she promoted a pan-Indian movement to unite all of America’s tribes in the cause of lobbying for citizenship rights. In 1924 the Indian Citizenship Act was passed, granting US citizenship rights to many though not all indigenous peoples.

Under pressure from the Women’s Clubs and others, the federal government agreed to the appointment of a commission to investigate the Indian situation. In 1928, this group, of which Gertrude Bonnin was an advisor, turned in its noted Report, under the supervision of Lewis Meriam. The following year President Hoover appointed two Indian Rights Association leaders to head the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal Administration took even more significant steps to reform United States Indian policy.

In 1926 she and her husband founded the National Council of American Indians, dedicated to the cause of uniting the tribes throughout the U.S. in the cause of gaining full citizenship rights through suffrage. From 1926 until her death in 1938, Zitkala-Ša would serve as president, major fundraiser, and speaker for the NCAI. She was the major figure in those years. Her early work was largely disregarded when the organization was revived in 1944 under male leadership.

Zitkala-Ša was also active in the 1920s in the movement for women’s rights, joining the General Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1921. It was a grassroots organization dedicated to diversity in its membership and to maintaining a public voice for women’s concerns. Through the GFWC she created the Indian Welfare Committee in 1924. She catalyzed a government investigation into the exploitation of Native Americans in Oklahoma and the attempts being made to defraud them of drilling rights to their oil-rich lands. Zitkala-Ša was co-author of “Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribe-Legalized Robbery.” The article exposed several corporations that had robbed and even murdered Native Americans in Oklahoma to gain access to their lands.

In her work for the NCAI in 1924, Zitkala-Ša ran a voter-registration drive among Native Americans. She encouraged them to support the Curtis Bill, which she believed would be favorable for Indians. Though the bill granted Native Americans US citizenship, it did not grant those living on reservations with the right to vote in local and state elections.

Its influence contributed to Congressional passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 under the President Franklin D. Roosevelt administration. He had high-level aides also working on American Indian issues to improve their lives. This legislation was sometimes described as the ‘Indian New Deal,’ and it encouraged tribes to restore and adopt self-government, along a model of elected representative government. which returned the management of their lands to Native Americans.

Zitkala-Ša continued to work for civil rights, and better access to health care and education for Native Americans up until her death in 1938.

Writings of Gertrude Simmons Bonnin

Photo by Gertrude Käsebier, 1898

Gertrude Simmons Bonnin had two prolific writing periods during her lifetime. The first period was from 1900 to 1904, when she published legends collected from Native American culture, as well as autobiographical narratives. She continued to write during the following years, but she did not publish. These unpublished writings, along with others including the libretto of the Sun Dance Opera, were collected and published as Dreams and Thunder: Stories, Poems, and The Sun Dance Opera by P. Jane Hafen in 2001.

Her articles in the Atlantic Monthly were published from 1900 to 1902. They included, “An Indian Teacher Among Indians” published in Volume 85 in 1900. Included in the same issue were “Impressions of an Indian Childhood” and “School Days of an Indian Girl”. All of these works were autobiographical in nature, describing in great detail her early experiences both on the reservation and her later conflict with struggling with assimilation with the dominant American culture.

Zitkala-Sa’s other articles ran in Harper’s Monthly. “Soft-Hearted Sioux” appeared in the March 1901 issue, Volume 102 and “The Trial Path” in the October 1901 issue, Volume 103. She also wrote “A Warrior’s Daughter”, published in 1902 in Volume 4 of Everybody’s Magazine. These works also were largely autobiographical in nature, though there were some that told the stories of those she knew or taught in addition to her own personal story.

In 1902 she published another article in Atlantic Monthly, volume 90, entitled, “Why I Am a Pagan”. It was a treatise on her personal spiritual beliefs, in which she countered the trend of the time that suggested Native Americans readily adopted and conformed to the Christianity forced on them in schools and public life.

The second period was from 1916 to 1924. During this period, Zitkala-Ša concentrated on writing and publishing political works. She and her husband had moved to Washington, D.C., where she became politically active. She published some of her most influential writings, including American Indian Stories (1921) with the Hayworth Publishing House.[28] She co-authored Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes, Legalized Robbery (1923), an influential pamphlet, with Charles H. Fabens of the American Indian Defense Association and Matthew K. Sniffen of the Indian Rights Association. She also created the Indian Welfare Committee of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, working as a researcher for it through much of the 1920s.

American Indian Stories is a collection of childhood stories, allegorical fiction, and an essay, including several of Zitkala-Ša’s articles that were originally published in Harper’s Monthly and Atlantic Monthly. It was first published in 1921 and served as an account of the hardships which she and other Native Americans encountered when they were brought to missionary and manual labor schools designed to “civilize” them. The autobiographical writings described her early life on the Yankton Reservation, her years as a student at White’s Manual Labor Institute and Earlham College, and the time she spent teaching at Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Commissioned by the Boston publisher Ginn and Company, Old Indian Legends (1901) was a collection of stories which she had gathered from various tribes. Directed primarily at children, the collection was an attempt both to preserve Native American traditions and stories in print and to garner respect and recognition for those traditions from the dominant white culture.

One of Zitkala-Ša’s most influential pieces of political writing, Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians was published in 1923 by the Indian Rights Association. The article exposed several American corporations that had been working systematically through such extra-legal means as robbery and even murder to defraud Native American tribes, particularly the Osage, to their rights to a plot of oil-rich land in Oklahoma. The work influenced Congress to pass the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which encouraged tribes to re-establish self-government, including management of their lands, and returned some surplus lands to them as communal property.

Zitkala-Ša was an active member of the Society of American Indians, which published the American Indian Magazine. From 1918 to 1919 she served as editor for the magazine, as well as contributing numerous articles. These were her most explicitly political writings, covering topics such as the contribution of Native Americans to WWI, land allotment, and corruption within the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the agency within the Department of Interior that oversaw American Indians. Many of her political writings have since been criticized for favoring assimilation. She called for recognition of Native American culture and traditions, while also advocating US citizenship rights to bring Native Americans into mainstream America. She believed this was how they could gain political power

For a more comprehensive listing of all her writings see the American Native Press Archives maintained by the Sequoyah Research Center at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock.

Zitkala-Ša died on January 26, 1938 in Washington, DC at the age of sixty-one. She is buried under the name of Gertrude Simmons Bonnin in Arlington National Cemetery. Since her death the University of Nebraska has reissued many of her writings on Native American culture.

In 1997 she was designated a Women’s History Month Honoree by the National Women’s History Project.

Biography of her life: Red Bird, Red Power: The Life and Legacy of Zitkala-a