Famous Nez Perce

Famous Nez Perce chiefs, leaders, and mediicine men

Hal-hal-hoot-soot, a.k.a. Chief Lawyer to the whites – He was the son of Twisted Hair. He was designated as Head Chief of the Nez Perce for the signing of the 1855 and controversial 1863 Treaty.

He was called the Lawyer by fur trappers because of his oratory and ability to speak several languages. His father’s positive experiences with the whites greatly influenced him, and he was the leader of the treaty faction of the Nez Percé, who signed the Walla Walla Treaty of 1855.

He defended the actions of the 1863 Treaty which cost the Nez Perce nearly 90% of their lands after gold was discovered because he knew it was futile to resist the US Government and its military power. He tried to negotiate the best outcome which still allowed the majority of Nez Perce to live in their usual village locations.

He died, frustrated that the US Government failed to follow through on the promises made in both Treaties even making a trip to Washington, DC to express his frustration.

Old Chief Joseph (Tuekakas), (also: tiwíiteq’is) a.k.a. Joseph the Elder, was leader of the Wallowa Band of Nez Perce. He was one of the first Nez Percé converts to Christianity and a vigorous advocate of the tribe’s early peace with the whites. He was the father of Chief Joseph (also known as Young Joseph).

Chief Joseph (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904) (Hinmatóoyalahtq’it or Hinmuuttu-yalatlat or Hinmaton-Yalaktit – “Thunder traveling to higher areas” or In-mut-too-yah-lat-lat – “Thunder coming up over the land from the water” or Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekht – “Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain” – Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekht is what is engraved on his grave.), also known as Young Joseph or Joseph the Younger, nicknamed the Red Napoleon by the American press after his surrender, in the mistaken belief that he planned the brilliant war strategies used in the Nez Perce War.

Chief Joseph’s role in this war was that of camp supervisor and guardian. He was entrusted with handling the logistics of camp and travel, and taking care of the women, children, and old people.

Chief Joseph was probably the best-known leader of the Nez Perce, who led his people in their struggle to retain their identity. With about 60 warriors left when he surrendered on behalf of the Non-Treaty Nez Perce, he commanded the greatest following of the non-treaty chiefs.

However, he was not the only chief whose people took flight on an epic attempt to escape white control that lasted three months and covered 1,170-miles (1,883 km) across four states and multiple mountain ranges.

Eighteen battles, skirmishes, and engagements were fought along the way, and became known as the Nez Perce War. His brother Ollokot, Looking Glass, Peo Peo Tholekt, Toohoolhoolzote, Yellow Wolf, Yellow Bull, White Bird, Red Owl, and Rainbow were among the war chiefs. Chief Joseph was a hereditary peace chief who was responsible for political negotiations and decisions affecting daily life in his Wallowa Band.

Once the peace was broken, war chiefs took over during battles.In the beginning of the flight, the combined Nez Perce bands, along with a band of Palouse Indians, numbered about 2900. Of this number about 750 were warriors. They were pursued by 2,000 US Calvary soldiers. Initially they had hoped to take refuge with the Crow nation in the Montana Territory, but when the Crow refused to grant them aid, the Nez Perce went north in an attempt to reach asylum with Sioux Chief Sitting Bull and his followers, who had fled to Canada in 1876.

Chief Joseph finally surrendered with most of his remaining tribe on October 5, 1877, just 40 miles shy of the Canadian Border in a blizzard because they were outnumbered, starving, and freezing to death because they didn’t have enough blankets, and General Howard promised to return them to the Wallowa Valley. Some Nez Perce did escape into Canada, and remain there today.

In the children’s fiction book, Thunder Rolling in the Mountains, by Newbery medalist Scott O’Dell and Elizabeth Hall, the story of Chief Joseph is told by Joseph’s daughter, Sound of Running Feet.

Kamiakin – Nez Perce leader who opposed the treaty of 1863.

Kipkip Pahlekin –

Ollokot, (’álok’at, also known as Ollikut) – He was the younger brother of Chief Joseph, and war chief of the Wallowa band. Many historians believe it was Ollokot who planned the brilliant strategy of the retreat and battles fought by the Nez Perce in their famous retreat to the Canadian border.

He was killed while fighting at the final battle on Snake Creek, near the Bear Paw Mountains on October 4, 1877.

Looking Glass, the Elder (Allalimya Takanin) leader of the non-treaty Alpowai band and war leader, was killed during the tribe’s final battle with the US Army. His following was reduced to a third and did not exceed 40 fighting men.

Looking Glass, the Younger –

Eagle from the Light, (Tipiyelehne Ka Awpo) chief of the non-treaty Lam’tama band, that traveled east over the Bitterroot Mountains along with Looking Glass’ band to hunt buffalo. He was present at the Walla Walla Council in 1855 and supported the non-treaty faction at the Lapwai Council, refused to sign the Treaty of 1855 and Treaty of 1866.

He left his territory on the Salmon River (two miles south of Corvallis) in 1875 with part of his band, and tried to settle down in Weiser County (Montana), and was joined with Shoshone Chief Eagle’s Eye. The leadership of the other Lam’tama that rested on the Salmon River was taken by old chief White Bird. Eagle From the Light didn’t participate in the War of 1877 because he was too far away.

Owhi – Nez Perce leader who opposed the treaty of 1863.

Peo Peo Tholekt (piyopyóot’alikt – “Bird Alighting”), a Nez Perce warrior who fought with distinction in every battle of the Nez Perce War, wounded in the Battle of Camas Creek.

Chief Red Heart – Nez Perce chief, who along with 33 members of his family and band, who were captured on July 1, 1877 and taken by steamship to Fort Vancouver where they were imprisioned from August 1877 to April 22, 1878 before being relocated to the Nez Perce Reservation.

Red Thunder – Nephew of Chief Joseph

Smohalla, Shaman who founded the Dreamer cult.

Toohoolhoolzote, was leader and tooat (meaning “medicine man or shaman or prophet”) of the non-treaty Pikunan band. He fought in the Nez Perce War after first advocating peace, and died at the Battle of Bear Paw.

Yellow Wolf or He–Mene Mox Mox or Hemeneme Moxmox or He-men Moxmox (a nickname given him by the whites. It refers to a Yellow Wolf he saw in a vision on his vision quest- his weyekin.) (born c. 1855, died August 1935) , a.k.a. Heinmot Hihhih or In-mat-hia-hia – “White Lightning” (his preferred name), c. 1855, died August 1935) was a Nez Perce warrior of the non-treaty Wallowa band who fought in the Nez Perce War of 1877.

He received a gunshot wound in his left arm near the wrist; and under his left eye in the Battle of the Clearwater, but survived his wounds.

Yellow Bull (Chuslum Moxmox, Cúuɫim maqsmáqs), war leader of a non-treaty Nez Perce band.

White Bird (Peo-peo-hix-hiix, piyóopiyo x̣ayx̣áyx̣ or more correctly

Peopeo Kiskiok Hihih – “White Goose”), also referred to as White Pelican was war leader and tooat (Medicine man or Shaman or Prophet) of the non-treaty Lamátta or Lamtáama band, belonging to Lahmatta (“area with little snow”), by which White Bird Canyon was known to the Nez Perce. His following was second in size to Joseph’s, and did not exceed 50 men. On the night Chief Joseph surrendered, he slipped away and led his people into Canada.

Walammottinin (Hair Bunched and Tied, but more commonly known as Twisted Hair )- In 1805, Lewis and Clark entrusted him and two others to keep their horses while they continued to the Pacific Ocean in boats. Father of Timothy, a prominent member of the pro treaty faction in 1877.

Wrapped in the Wind (’elelímyeté’qenin’/ háatyata’qanin’) –

Rainbow (Wahchumyus), war leader of a non-treaty band, ), who became the father of Timothy, a prominent member of the “Treaty” faction in 1877. killed in the Battle of the Big Hole.

Five Wounds (Pahkatos Owyeen), He was wounded in right hand at the Battle of the Clearwater and killed in the Battle of the Big Hole.

Red Owl (Koolkool Snehee), He was a war leader of a non-treaty band.

Poker Joe, a.k.a. Lean Elk – He was half French Canadian and Nez Perce. He was a warrior and subchief. He was chosen trail boss and guide of the Nez Percé people following the Battle of the Big Hole. He was killed in the Battle of Bear Paw.

Timothy (Tamootsin, 1808–1891), leader of the treaty faction of the Alpowai (or Alpowa) band of the Nez Percé. He was the first Christian convert among the Nez Percé, was married to Tamer, a sister of Old Chief Joseph, who was baptized on the same day as Timothy.

Archie Phinney (1904–1949), He was a scholar and administrator who studied under Franz Boas at Columbia University and produced Nez Perce Texts , a published collection of Nez Perce myths and legends from the oral tradition.

Elaine Miles, Actress best known from her role in television’s Northern Exposure.

Jack and Al Hoxie, Silent film actors. Their mother was Nez Perce, father unknown heritage.

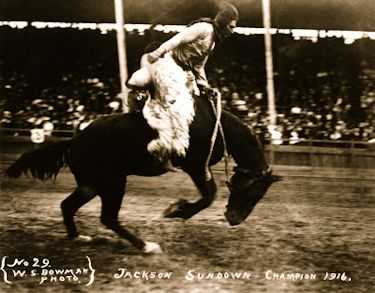

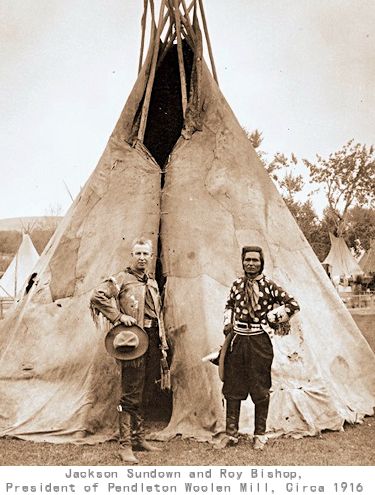

Jackson Sundown (Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, meaning “Blanket of the Sun” or “Earth Left by the Setting Sun.” ) a.k.a. , (1863-December 18, 1923) Nez Perce war veteran and rodeo champion. He was the first native American to win the World Saddle Bronc Championship at the 1916 Pendleton Round-Up. He was a nephew of Chief Joseph.

Claudia Kauffman, a former state senator in Washington state.

Fool Soldiers – A drum group that includes members of several nations, including Sans Ark Lakota, Nez Perce, Colville, Tshimsin, Turtle Mountain Chippewa, Crow, Assiniboine-Sioux, Yakama, and Umitilla.

Red Tail Singers – A drum group of Yakama & Nez Perce from Lapwai, ID

Nez Perce Tribes:

Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation (Chief Joseph’s Band) (F) (Washington)

Coeur d’ Alene Tribe (A small remnant of Nez Perce live on this reservation.)

Nez Perce Tribe of Idaho (F) (Idaho)

Article Index:

Jackson Sundown, a nephew of Chief Joseph, was with him on the flight of the Nez Perce in 1877. He was the first native American to win a World Championship Bronc Rider title in 1916, at the age of 53, more than twice the age of the other competitors who made it to the final round. He is also the oldest person to ever win a rodeo world championship title. He was posthumously inducted into the Pendleton Round-Up Hall of Fame in 1972, into the National Cowboys of Color Museum and Hall of Fame in 1983, and the American Indian Athletes Hall of Fame in 1994.

Jackson Sundown, a nephew of Chief Joseph, was with him on the flight of the Nez Perce in 1877. He was the first native American to win a World Championship Bronc Rider title in 1916, at the age of 53, more than twice the age of the other competitors who made it to the final round. He is also the oldest person to ever win a rodeo world championship title. He was posthumously inducted into the Pendleton Round-Up Hall of Fame in 1972, into the National Cowboys of Color Museum and Hall of Fame in 1983, and the American Indian Athletes Hall of Fame in 1994.

Jackson Sundown (Born 1863-Died December 18, 1923)

a.k.a. George Jackson and Buffalo Sundown,

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn (meaning “Earth Left by the Setting Sun”), also spelled We-ah-te-nato-ots-ha (meaning “Blanket of the Sun”)

Tribal Affiliation: Nez Perce

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn (Jackson Sundown) from an early age worked with and cared for horses. At the age of 14, he was appointed, along with Sam Tilden (Suhm-Keen), to care for and watch over the horses at night on the Nez Perce flight which is called the Nez Perce War of 1877. At the Battle of the Big Hole, he was sleeping in his mother’s tipi when the battle broke out and when soldiers began gathering up prisioners, he hid under a buffalo robe. He was severely burned when a soldier set the tipi on fire.

When Joseph surrendered to General Miles in the Bear Paws of Montana, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn escaped with rifle wounds and made his way to Sitting Bull’s Sioux camp in Canada with White Bird’s group. It is said he escaped by hanging off the side of his horse, making it appear the horse was unmounted.

When he reached Canada, he was given asylum by Sitting Bull and the other Sioux warriors who defeated Custer in 1876. No one seems to know for sure, but it is reported by most historians that he stayed in Canada for two years and was considered a war criminal by the US.

After two or three years in Canada, he crossed back into the United States and made his way to the Flathead Reservation in Montana.

After two or three years in Canada, he crossed back into the United States and made his way to the Flathead Reservation in Montana.

Olive C. Wehr in “To Live On A Reservation ,” writes: “After two years, he stealthily rode to Nespelem, Wash., where Joseph and his surviving followers were confined to a small reservation away from their beloved hills of Wallowa. Joseph warned him not to go there, so Sundown went instead to the Flathead Reservation.”

This story can’t be right, because after Chief Joseph surrendered in 1877 he was first sent to prison at Fort Leavensworth, Kansas for eight months, and then exiled to Indian Territory in Oklahoma for a number of years. Chief Joseph wasn’t moved to Nespelem, Washington on the Colville Reservation until 1885. So either this part of his story isn’t true or the dates are mixed up.

Anyway, when he got to the Flathead Reservation, a Salish woman named Pewlosap (Annie to the whites) took him into her lodge and they lived together without a formal marriage. He had two daughters with his common law wife, Adaline and Josephine.

Adaline Redsky Sundown was born May 26, 1896 near Ronan, in what was then Missoula County and died in August of 1977 at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Polson, MT. She had been married four times to: Louie Hammer, Michel Parker (they had a son Joseph Larry “Itsteenicnukt” Parker, who could speak Salish; Nez Perce, German, Spanish, Russian, and Kootenai.), Pierre Isadore “Peter” Woodcock and finally Pierre Adams (they had a son Patrick Adams, who was a hoop dancer on the Bicentennial Train trip to Washington, D.C.).

Adaline Redsky Sundown was born May 26, 1896 near Ronan, in what was then Missoula County and died in August of 1977 at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Polson, MT. She had been married four times to: Louie Hammer, Michel Parker (they had a son Joseph Larry “Itsteenicnukt” Parker, who could speak Salish; Nez Perce, German, Spanish, Russian, and Kootenai.), Pierre Isadore “Peter” Woodcock and finally Pierre Adams (they had a son Patrick Adams, who was a hoop dancer on the Bicentennial Train trip to Washington, D.C.).

A note in a journal kept by the St. Ignatius Mission House dated Jan. 6, 1909 noted, “Some Nez Perces who are living like beasts have been ordered out of the Reservation, or to get married.”

On February 12, 1909, their records also recorded that a Flathead Indian named Baptist Kakaeshin or Baptiste Ka Kaeshin or Kakashe made an unauthorized trip to Washington to make known some crooked dealings occurring on the Flathead Reservation he did not agree with. He wanted to take Jackson with him as an interpreter. The Agent forbade this, “because he is a stranger and living in adultery.”

On February 12, 1909, their records also recorded that a Flathead Indian named Baptist Kakaeshin or Baptiste Ka Kaeshin or Kakashe made an unauthorized trip to Washington to make known some crooked dealings occurring on the Flathead Reservation he did not agree with. He wanted to take Jackson with him as an interpreter. The Agent forbade this, “because he is a stranger and living in adultery.”

Kakaeshin then agreed to have Joe Pierre interpret but when they got to Missoula, Pierre returned to the reservation and Sundown went with Kakaeshin, deliberately disobeying the Agent’s orders.

Their complaints were that the land north of the Flathead Reservation was not ceded to the U.S. government; the tribe had not consented to the allotment and opening of the reservation; [and that]William Q. Ranft was charging to get people enrolled; that Joe Dixon has forged the consent of tribal leaders on a petition to open the reservation to settlement.

Their complaints were that the land north of the Flathead Reservation was not ceded to the U.S. government; the tribe had not consented to the allotment and opening of the reservation; [and that]William Q. Ranft was charging to get people enrolled; that Joe Dixon has forged the consent of tribal leaders on a petition to open the reservation to settlement.

The BIA Agent’s report on the matters brought up states, “The treaty provides to cession of all land claims except reservation; …that the matter of making allotments and providing for the future support of the Indians has been frequently investigated by officials of the Department, and that it was thought to be best for the welfare of the Indians. BIA has no information on charges for enrollment, and will continue to protect the Indians.”

In regard to the Dixon Allotment Law, he says, “The law was not passed on the petition of the Indians. Congress had the power to make the law and did not ask the consent of the Indians. [The trip to Washington,] D.C. was not needed and normally the BIA does not recognize unauthorized delegations but …I have made an exception in your case out of respect to the advanced age of Baptiste, who has traveled this long distance at much discomfort to himself, no doubt.”

In regard to the Dixon Allotment Law, he says, “The law was not passed on the petition of the Indians. Congress had the power to make the law and did not ask the consent of the Indians. [The trip to Washington,] D.C. was not needed and normally the BIA does not recognize unauthorized delegations but …I have made an exception in your case out of respect to the advanced age of Baptiste, who has traveled this long distance at much discomfort to himself, no doubt.”

Shortly after that, according to the the St. Ignatius Mission House records, the new Indian Agent Fred Morgan announced to Father Taelman that Baptist KaKaeshe is no longer a judge, in punishment for having gone to Washington against the will of the former Agent, and he asks for a recommendation for his replacement. No mention is made about any punishment for Jackson Sundown.

In 1910, Sundown rejoined his tribe on the Nez Perce Indian Reservation in Lapwai, Idaho, where he took an allotment of land and built a cabin. He later married Cecelia Wapshela in 1912, and they built a home at Jacques Spur, Idaho.

In 1910, Sundown rejoined his tribe on the Nez Perce Indian Reservation in Lapwai, Idaho, where he took an allotment of land and built a cabin. He later married Cecelia Wapshela in 1912, and they built a home at Jacques Spur, Idaho.

That first summer at Lapwai, when he was 47, at the age most rodeo cowboys are retiring from the circuit, Jackson took his first competition ride. At a rodeo in Culdesac, Idaho, on a dare he rode a notorious bronc, did a standing dismount and them calmly dusted off his blue serge suit. The croud went wild.

That’s where he got the idea to enter rodeo competitions as a way of earning some extra money.

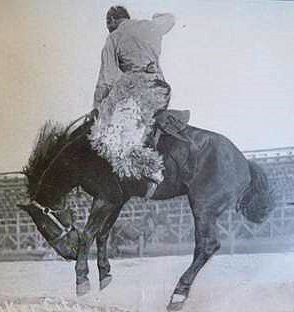

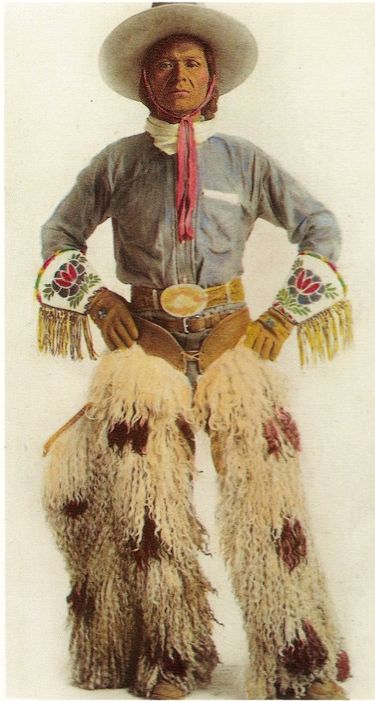

The six foot tall, lean and handsome cowboy didn’t look much like the other cowboys of his era. Aside from the fact that there weren’t many “men of color” competing in rodeos in that era, he didn’t dress like the other cowboys. He wore his long hair in the traditional Nez Perce pompadour, with braids that were tied together and held under his chin with a colorful bandana. He was partial to brightly colored shirts, wore huge angora wool chaps with spots on them, and his favorite shirt was also covered in spots. His gloves were colorfully beaded with a flower pattern. Instead of the usual western cowboy hat, he wore a high, wide brimmed “Indian Hat.” He was quickly a favorite of the rodeo fans.

He wore his long hair in the traditional Nez Perce pompadour, with braids that were tied together and held under his chin with a colorful bandana. He was partial to brightly colored shirts, wore huge angora wool chaps with spots on them, and his favorite shirt was also covered in spots. His gloves were colorfully beaded with a flower pattern. Instead of the usual western cowboy hat, he wore a high, wide brimmed “Indian Hat.” He was quickly a favorite of the rodeo fans.

Roy Bishop, the president of the world famous Pendleton Woolen Mills, was so impressed with some of his clothing that he wove some of the patterns into his famous Pendleton blankets. The two men became lifelong friends.

Jackson won many all-around cash pots, which takes the highest average scores from all events, and was also a pretty good bull rider, though he was best known for bareback and saddle bronc horse riding.

By the next year, he had earned enough points to qualify for the Saddle Bronc Finals for the 1911 World Championship at the Pendleton Round-Up, which ended in controversy and protest.

He competed with George Fletcher, an African American, and John Spain, a European American.”

The Moscow Pullman Daily News reported that Sundown took third after falling from his horse which had slammed into one of the judges’ horses, but was not given a re-ride, which is usually given when there is interference with the ride.

Fletcher, who “thrilled the crowd with his first ride,” was ordered a re-ride by the judges, which “was as wild as the first,” and would be awarded second place.

Fletcher, who “thrilled the crowd with his first ride,” was ordered a re-ride by the judges, which “was as wild as the first,” and would be awarded second place.

Spain would be awarded the grand prize amid protests from the crowd claiming he had touched the horse with his free hand, which is an automatic disqualification in bronc riding events.

The town Sheriff Till Taylor is said to have taken Fletchers hat, torn it up and sold the pieces to the thousands of protestors. They handed Fletcher the proceeds and declared him “The Peoples Champion.”

Award-winning Western novelist Rick Steber chronicled the story in his book titled “Red White Black,” that forever changed the sport of rodeo, and the way the emerging West was to look at itself.

Ken Kesey, author of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” also wrote a book titled “Last Go Round,” that tells the story of the hustle and bustle around the 2nd annual Pendleton Round-Up rodeo in 1911.

In 1912 it is recorded that Jackson Sundown (at the age of 49) entered rodeo events in Canada and Idaho (Culdesac, Orofino, Kamiah and Grangeville). He continued to be a favorite with the crowds and more often than not, he was “in the money.”

In 1912 it is recorded that Jackson Sundown (at the age of 49) entered rodeo events in Canada and Idaho (Culdesac, Orofino, Kamiah and Grangeville). He continued to be a favorite with the crowds and more often than not, he was “in the money.”

By 1914 Sundown was having so much success as an all-around rodeo rider that other contestants pulled out of rodeos when they found out he was riding because they knew he would beat them. As a result the rodeo managers decided to hire Sundown to exhibition ride for $50.00 a day to entertain the crowds. He accepted this offer, which kept him in guaranteed money which was still a lot at the turn of the century, but cut him out of the chance to win the really big pots such as those at the Calgary Stampede, Pendleton, and other big rodeos.

In 1914 his regal bearing and presence attracted America’s most famous sculptor of that era, Alexander Phimster Proctor, who hired him to pose for many statues including one for Stanford University, the RCA Building in New York, as well as the heroic piece that now stands in front of the Colorado Capital building.

In 1915 at age 52, he again qualified for the World Championship competiton at the Pendleton Roundup. He placed third again that year, and decided to retire from rodeo, which had wrecked his body. Most rodeo cowboys had already retired by age 40, younger than he was when he first started competing. A discouraged Jackson said he was through with competitive riding where he felt he was not judged fairly, but Proctor talked him into “one more” and paid his entry fees for the 1916 Pendleton Roundup. His rides there are still called the most exciting and unbelievable in rodeo history.

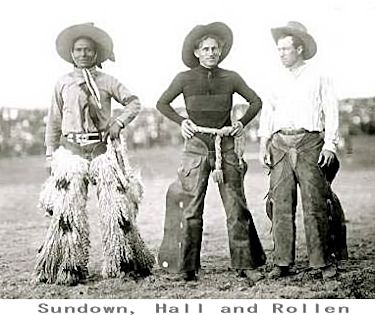

Pitted against him in the finals were two great bronc riders of the day, Rufus Rollen of Oklahoma and Bob Hall of Pocatello. Both men made epic rides, but the ride of Sundown eclipsed them both.

Pitted against him in the finals were two great bronc riders of the day, Rufus Rollen of Oklahoma and Bob Hall of Pocatello. Both men made epic rides, but the ride of Sundown eclipsed them both.

Sundown was twice the age of the other semi-finalists, but advanced after high scores in the saddle bronc and bareback horse riding competitions. His final ride is an event of great mythology to this day among American Indians and rodeo aficionados.

It is told that Sundown drew a very fierce horse named Angel that he had rode before. Angel twisted in circles before exploding into the air several times.

From the moment they left the gate, he spurred the horse from neck to flank continuously. Not for a moment did the punishment abate. They say the horse bucked so furiously that Sundown removed his hat and fanned the horse to get it to cool off, at which time he and the horse merged into one being.

A noisy crowd watched as the only full-blooded Indian ever to compete in the Pendleton Round-up Championship rode to victory. The very ground of the arena seemed to rock with the earth shaking leaps of the outlaw bronc. Sundown rode gloriously into the championship amid an ovation never before equaled. The throngs – White and Indians – cheered themselves hoarse. Sundown won the all-around event and became immortalized as both a cowboy and Indian hero.

When the 1916 World Champion Bronc Rider was awarded his handsome leather tool prize saddle and asked what he would like engraved on the silver plate, he replied Cecelia Wapshela, his wife’s name.

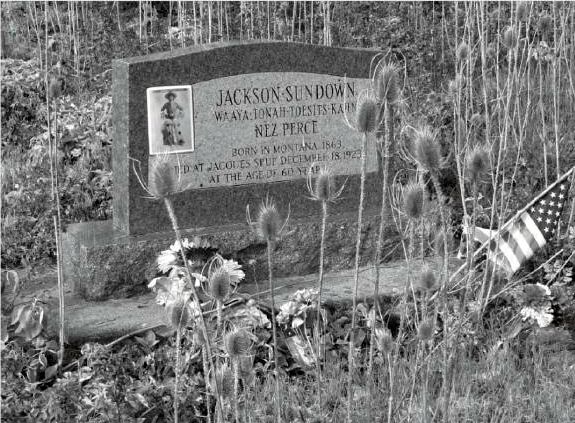

In 1923, Jackson Sundown died of pneumonia. He was buried at Slickpoo Mission Cemetery near Jacques Spur, Idaho. Sundown wasn’t even an American citizen when he died. Congress voted in 1924 to make American Indians citizens of the United States.

A stone monument placed on the grave of the Nez Perce warrior and legendary horseman reads: Jackson Sundown, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, Nez Perce, Born in Montana 1863, Died at Jacques Spur, December 18, 1923 at the age of 60 years, and has a picture of him in his wooly chaps.

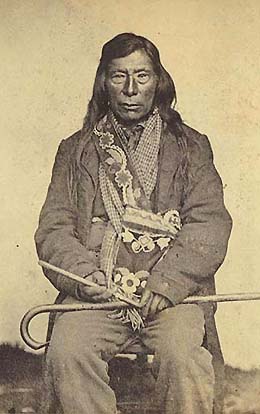

Chief Lawyer “Hal-hal-hoot-soot” was the son of a Salish speaking Flathead woman and Twisted Hair, the Nez Perce man who welcomed and befriended Lewis and Clark in the fall of 1805. He was designated as Head Chief of the Nez Perce for the signing of the 1855 and controversial 1863 Treaty.

Hallalhotsoot’s father had positive experiences with the white explorers, which greatly influenced Lawyer. He firmly believed that the best prospect for the future of the Nez Perce was through friendship with non-native peoples.

“Lawyer” was a nickname given to Hallalhotsoot by the mountain men of the early 1830s. He was known as “the talker,” and his speaking abilities and wisdom enabled him to influence both native and non-native peoples.

“Lawyer” was a nickname given to Hallalhotsoot by the mountain men of the early 1830s. He was known as “the talker,” and his speaking abilities and wisdom enabled him to influence both native and non-native peoples.

The Nez Perce and Christianity

In 1831, six Nez Perce embarked on a journey through the Rocky Mountains to invite Christian teachers to come to the tribes. Two of the party turned back at the mountains, but four proceeded on to St. Louis. The story was reprinted widely in American newspapers, and set off a frenetic missionary movement to the West, one that changed the course not only of the Nez Perce people, but of the entire Northwest.

One of these missionaries, Marcus Whitman, hired Lawyer to live at his mission and teach him the Salish and Nez Perce languages. Whitman provided food and clothing to Lawyer’s family in return. It was here that Lawyer, once a buffalo hunter, began to adapt to the culture and religion of the white man.

Lawyer emerged as a leader of the Nez Perce following the Whitman tragedy on November 29, 1847. He traveled to Salem to meet Joseph Lane, Governor of the Oregon Territory, and requested aid in the capture of the Whitmans’ murderers.

The Walla Walla Treaty Council of 1855

Lawyer’s friendly attitude toward white culture led Isaac Stevens to select him as the designated leader of the Nez Perce at the Walla Walla Treaty Council of 1855. Lawyer was one of the first chiefs to be sketched by the artist Gustav Sohon at that council, an indication of his importance among non-Native observers.

Sohon’s inscription describes Lawyer as Head Chief of the Nez Perce Tribe, but some observers believe he only became the main spokesman after being selected by Isaac Stevens.

After the Council In the years that followed the Walla Walla Council, Lawyer was widely ridiculed by anti-treaty groups within the Nez Perce tribe after the terms of the treaties failed to be honored by the U.S. government. When the promised payments began arriving in the early 1860s, cynical observers would note that they seemed timed to coincide with the government’s desire for more land from the Nez Perce.

The second treaty, signed by Lawyer in 1863, reduced the area of the tribe’s reservation by 90 percent, transferring away the homelands of many Nez Perce bands. This was done without their Lawyer defended his actions by arguing that resisting white encroachment was useless and that the wise and practical course was to simply adapt to changing circumstances.

Despite his trust that Governor Stevens and the American government had good intentions, Lawyer experienced great disappointment when promises made in the treaties were not honored.

In a speech delivered in the goldrush boomtown of Lewiston, Idaho, in 1864, Lawyer spoke eloquently to the failure of the government to live up to its promises:

If [Stevens] had told us that the reservation was to be flooded with white settlers, or that the saw mill was to be used for the exclusive benefit of the Whites, we would never have consented to the treaty. That flour mill and saw mill were pledged to me and my people. All the stipulations of that treaty were pledged to us for our benefit.>br?>br> Nine years have passed and those stipulations are unfulfilled.

[W]e have no church as promised; no schoolhouse as promised; no doctor as promised; no gunsmith as promised; no blacksmith as promised.

Lawyer devoted his life to making peace with the white population and following the terms of the treaties he signed. Nevertheless, in 1870—after holding his post for twenty-five years—he voluntarily stepped down from the leadership of the Nez Perce.

His descendants tell the tale of his death on January 3, 1876, in this manner:

It was Lawyer’s custom to fly his American flag from a pole in front of his lodge or house. On the day that he died, knowing that his end was near, he instructed some member to gradually pull down the flag.

The flag would be lowered a bit and then Lawyer, after a time would say: “Pull it down a little more.” So the flag was lowered a little more. This was repeated several times and when the flag touched the ground, Lawyer died.

Today many Nez Perce people continue to live in their homeland- some on and some off the reservation. Others have moved to cities around the country.

Sources:

Drury, Clifford M. Chief Lawyer of the Nez Perce Indians, 1796-1876 . Glendale, CA: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1979.

Josephy, Alvin M. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest (American Heritage Library).New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997.

Nicandri, David L. Northwest Chiefs: Gustave Sohon’s Views of the 1855 Stevens Treaty Councils .

Old Chief Joseph (Tuekakas), was leader of the Wallowa Band and one of the first Nez Percé converts to Christianity and a vigorous advocate of the tribe’s early peace with whites, and father of Chief Joseph (also known as In-mut-too-yah-lat-lat or Young Joseph). He was chief of the Nez Perce from 1785—1871.

Modern history first records Joseph, principal chief of the Wallowa band of Nez Perce, in 1834, when he welcomed Captain Benjamin Bonneville as he led the first white men into the Wallowa Valley. Joseph, father to the now more widely known Chief Joseph, was in his late forties at that time.

The Nez Perce treated the Bonneville party to a feast of deer, elk, and buffalo meat, served along with fish and roots, before they settled in for a long talk. Joseph was eager for news of the United States, and Bonneville did his best to sell him on the merits of the American nation.

Missionaries Come to Lapwai

When the missionaries Marcus Whitman and Henry Spalding arrived in Lapwai in 1836, they were intent on converting the Indians to Christianity. Joseph was drawn to the new religion, and moved to distant Lapwai for long periods of time for instruction.

In 1839 Joseph and Timothy were the first Nez Perce to be baptized into the Christian faith. Following his conversion, Joseph and his wife, Khapkhaponimi, who later came to be called Asenoth, married again in their new faith in Spalding’s church. Their children were also baptized, and given Christian names, including a boy, Ephraim, who was likely the future Chief Joseph of Nez Perce War fame.

Following the Whitman tragedy of 1847, the influence of the missions was broken, and Joseph returned to Wallowa Valley. By some accounts he then reverted to his native beliefs, but others describe him as a practicing Christian and friend of the whites for at least another fifteen years.

Treaty Councils

At the Walla Walla Council of 1855, Joseph remained largely quiet, saying only, “I have a good heart, what the Lawyer says, let it be.” When the call for signatures came, Joseph signed along with the other chiefs. But in the years that followed he refused to accept treaty payments, insisting that he had given nothing at Walla Walla and expected nothing in return.

Joseph refused to sign the treaty drawn up at the Lapwai Council in 1863, and by that time the reservation had been so reduced in size that his homelands were now outside its borders. From that point on, Joseph became a leader of the “non-treaty” Nez Perce. He erected boundary monuments to mark his land, and destroyed the Bible given to him by Spalding many years earlier. With this symbolic gesture, Joseph turned his back on the American government.

By 1869, Joseph had gone blind, although he continued to instruct his sons with regard to his perceptions of white men, treaties, and Mother Earth. He told them, “when you go into council with a white man, always remember your country. Do not give it away. The white man will cheat you out of your home.”

Gravesite of Old Chief Joseph in Wallowa Valley, Oregon – See Genealogy Chart

Upon his deathbed, old Joseph told his son:

When I am gone, think of your country. You are the chief of these people. They look to you to guide them. Always remember that your father never sold the country. You must stop your ears whenever you are asked to sign a treaty selling your home. A few years more, and the white man will be all around you. They have their eyes on this land. My son, never forget my dying words. This country holds your father’s body. Never sell the bones of your father and your mother.

Nez Perce War

By 1877, the federal government had tried to force the “non-treaty” bands, including the Wallowa Nez Perce, now led by Young Chief Joseph (Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekht), out of their homelands and onto the more restricted reservation. The Indians’ response was the Nez Perce War.

“For decades,” wrote Robert Ignatius Burns, “the Nez Perce were considered as tame Indians, underrated and even mistreated despite their unswerving friendship for the Whites. They won fame and respect only when they went to war.”

Although young Chief Joseph’s brilliance as a war chief won sympathy from the American public, when defeat came to the defiant Nez Perce, they were nevertheless sent into exile at the Colville and Lapwai agencies.

Old Chief Joseph is buried at the fork of the Lostine and Wallowa Rivers on the Nez Perce homelands in what is now Oregon.

Sources:

Drury, Clifford M. Chief Lawyer of the Nez Perce Indians, 1796-1876. Glendale, CA: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1979.

Nicandri, David L. River of Promise: Lewis and Clark on the Columbia Tacoma: Washington State Historical Society, 1986.

Josephy, Alvin The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997.

Josephy, Alvin M. The Patriot Chiefs: A Chronicle of American Indian Resistance. New York: Penguin Books, 1976.

Burns, Robert Ignatius. The Jesuits and the Indian Wars of the Northwest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1966.