Blackfeet Indians

The Blackfeet Indians are a plains tribe who were traditional enemies of just about everyone, including the Crow, Shoshone and Nez Perce, with whom they shared buffalo hunting grounds.

They are one of the few tribes whose reservations and reserves were actually carved out of a portion of their traditional homelands and are located on the land they requested.

Tribal Origin: Algonquian

Native Name: Niitsítapi (meaning the Blackfoot Confederacy)

Siksikaikwan, meaning “a Blackfoot person.”

Siksika is a derivative of Siksikaikwan meaning “black foot,” which is what the Blackfoot tribes called themselves collectively, and is also the name of the northernmost division of the Blackfoot Tribe. It refers to the dark color moccasins worn by the people.

The Blackfeet Indians also referred to themselves as Sawketakix, meaning “men of the plains.”

The Blackfoot Confederacy also called themselves collectively the Netsepoyè, meaning “people who speak our language.”

Alternate Names: Northern Blackfoot, Southern Blackfoot, Far Southern Blackfoot, Siksika, Bloods (Ah-hi’-ta-pe, Kainai or Akainawa), and the Peigan (variously spelled Piikani, Pikani, Pikuni, Piegan, or Pikanii).

Although “Blackfeet” is the official name of this tribe in the United States, the word wasn’t plural in their language. This was changed by the US government to the Blackfeet Nation of Montana, located in Browning, Montana. They especially, resent this label and still prefer to be called Blackfoot.

However, most people today use the terms Blackfoot and Blackfeet Indians interchangably to mean the same group of people.

The Blackfeet Nation is divided into three divisions which make up four modern day tribes, one in the United States in northern Montana and three in Canada in southern Alberta.

The Blackfeet Indians share a historical and cultural background but have separate leadership. All the different names used to refer to these tribes can be confusing.

They are the Siksika (which means “Black Foot”), the Bloods (also called Kainai or Akainawa), the Peigan (variously spelled Piikani, Pikani, Pikuni, Piegan, or Pikanii) in Canada, and the Blackfeet Nation in the US living on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Montana.

Siksika (black foot) was the term they called themselves to mean all the Blackfoot peoples collectively, but today is the name used by the Northern Blackfoot in Canada.

The Ah-hi’-ta-pe (blood people), commonly called Bloods today, are the same people as the Kainai (many chiefs), and were the Southern Blackfoot, now primarily in Canada.

The term “Blood” was used by English speakers to refer to the people of the Kainai First Nation. The term originally derives from the Cree reference to the Kainai as “red people” because of the ochre they spread on their clothes. This was later translated as “blood people” or “blood.”

According to legend, the name for the Kainai First Nation came from a traveler visiting the Kainai wishing to meet with the chief, but everyone he spoke to claimed to have Chief rank. The traveller referred to them as Akainai, which means “many chiefs.” Kainai is a derivative of Akainai, and is the name by which the members of the Kainai First Nation know themselves.

Peigan is a corrupted version of the word Apikuni, meaning “scabby hides”, and this term became commonly used to refer to the Piikani people, and refers to the poorly tanned hides used to make women’s clothing.

Spellings of this term vary depending on whether one is north or south of the Canada / United States border. The Canadian group is known simply as the “Peigans” while their relatives south of the border are the “Piegans”

Pikuni (scabby robes) and Piegan are used interchangeably to mean the Blackfoot people who lived even farther south than the Bloods.

The Piikani are the southernmost nation of the Blackfoot, and the most populous. Due to contradictory traditions, it is difficult to know for sure where the term Piikani comes from.

However, the word Apikuni which means “scabby hides” seems to make way for the history of the term.

Most Pikuni or Piegans are known as the Blackfeet Tribe of Montana today, although there are some Peigans in Canada. There are also some Siksika people who belong to the Blackfeet Tribe of Montana.

The Blackfoot and Blackfeet were once one nation, which has been divided by modern day international borders.

Canadian Peigans have treaty rights to freely cross the US – Canadian border and retain dual citizenship in both countries, while the Piegans on the US side of the border do not.

The border between the US and Canada was called the “medicine line” by the Blackfeet Indians, because for some reason unknown and magical to them, the Canadian Mounties would stop chasing them when they crossed the line heading south with contraband whiskey. Likewise, the Americans would stop the chase at this line when they ran to the north.

The Northern Peigans or Aapátohsipikáni are a First Nation, part of the Niitsítapi (Blackfoot Confederacy). Known as Piikáni, “Pekuni” or Aapátohsipikáni (Northern Piikáni/Peigan), they are very closely related to the other members of the Blackfoot Confederacy: Aamsskáápipikani (the Blackfeet of Montana or Southern Piikáni/Peigan), Káínaa or Blood and the Siksiká or Blackfoot.

At the time treaties were signed, the Northern Peigan were situated on the Oldman River, west of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada, to the west of the Kainah tribe. The modern reserve (which includes the town of Brocket) is located near Pincher Creek.

Home Territories: North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana in the United States, and Alberta, Canada

Traditional Territory:

The relations of the Blackfoot language to others in the Algonquian language family indicate that the Blackfoot once lived in an area west of the Great Lakes.

Though they practiced some agriculture, they were partly nomadic. They moved westward partially because of the introduction of horses and guns and became a part of the Plains Indians culture in the early 1800s.

However, there is evidence that they were near the rocky mountain front for thousands of years before European contact.

The Siksika Blackfoot, fiercely independent and very successful warriors, controlled a vast region stretching from the North Saskatchewan River in Alberta to Yellowstone River of Montana, and from the Rocky Mountains to the Cypress Hills on the Alberta-Saskatchewan border.

It was not until the coming of the North West Mounted Police in 1874, over 110 years ago, that Euro-Canadian settlement in the region began.

Until the near extinction of the buffalo in 1881, the Blackfoot pursued their traditional lifeways. Only with the loss of their food supply were they obliged to adapt to the new era.

Geograpical Location Today:

With the signing of Treaty No. Seven in Canada in 1877 and the demise of the buffalo shortly thereafter, most of the Siksika Blackfoot settled on reserves in southern Alberta. Nineteen hundred of them are now gathered on the Blackfeet reservation in Montana, the rest being in the adjacent Canadian province of Alberta. Associated with them are two smaller tribes, the Atsína (Gros Ventres) and the Sarsi.

Reserve:

Siksika Nation is located one hour’s drive east of the city of Calgary, and three kilometres south of the Trans Canada Highway #1. The Administrative and Business district are located adjacent to the Town of Gleichen, Alberta, Canada.

Reservation:

Blackfeet Reservation of Browning,Montana

Enrolled Population:

Siksika Nation has a total population of approximately 4,200 members. Approximately 1,900 Siksika are enrolled in the Blackfeet Nation located at Browning, Montana.

Language: Algonquian – Niitsipussin (meaning the Real Language in Blackfoot, or Blackfoot in English).

All of these nations share a common language and heritage. They speak an Algonquian dialect of the Algic language family. Some differences in phraseology occurs among the Niitsitapi divisons, but essentially, the language is the same.

Many Blackfeet Indeians still speak their traditional language, and it is one of the few indigenous languages in Canada and the United States which has a good chance for survival.

About half of all Blackfeet people are bilingual and speak both English and their traditional language.

The public school on the Blackfeet Reservation at Browning, Montana has a total emersion language program where elementary students are taught in the Blackfoot language.

Blackfoot Enemies: Crow, Shoshone, Nez Perce, Dakota, Lakota and Nakota

The Blackfeet Indians were the most feared Indian nation on the Northern Plains in the nineteenth century. A fiercely aggressive people, they drove weaker groups from their lands and fought with their neighbours, taking scalps, raiding camps and running off with their horses

The Blackfeet Indians were constantly at war with all their neighbors except the Atsina and Sarci, who lived under their protection.

The Atsína (Gros Ventre) had been allies of the Blackfoot for generations, but a dispute with the Piegans over stolen horses in 1863 turned them into bitter enemies.

The Cree, Assiniboin, Sioux, Flatheads, and Kutenai were often under attack by the Blackfeet Indians. but their main rivals were the Crow Indians.

Points of Interest:

Blackfoot artists are known primarily for their fine quill embroidery and beadwork.

The big pow wow on the Browning reservation is called North American Indian Days and is held the weekend following the 4th of July each year.

There is also a nice museum showcasing the Blackfeet Indian culture in Browning, which lies on the eastern edge of Glacier National Park.

Blackfoot Confederacy:

The Blackfoot Confederacy is formed from four closely related First Nations: Siksika (also called Northern Blackfoot), Kainah (also called Blood), South Pikuni (Piegan, located in Montana – now known as the Blackfeet in the United States), and North Pikuni (Peigan, located in Alberta).

A fifth Blackfoot group, the Small Robes, was nearly wiped out by a smallpox epidemic in the 1830s, and the remaining remnant were massacred by the Crows.

Later, in the early 1800s, the Tsuu T’ina or Sarcee First Nation would join this alliance.

A Sarcee, Pat Grasshopper, claimed his tribe was originally named Saxsiiwak, meaning “hard or strong people.” In their own language, they call themselves tsotli’na meaning “Earth people.”

They are also called the Tsuu T’ina, which translates as “a great number of people.”

Is it Blackfoot or Blackfeet Indians?

“Blackfoot” is the English translation of the word siksika, which means “black foot.” It refers to the dark colored moccasins the people wore. Some Blackfoot people are annoyed by the plural “Blackfeet Indians” which is obviously an anglicization. But most Blackfoot people accept both terms.

“Blackfoot” is the more common spelling used in Canada, and “Blackfeet” is the official U.S. Government spelling used in the United States, due to the US Government’s naming of the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana with the plural form.

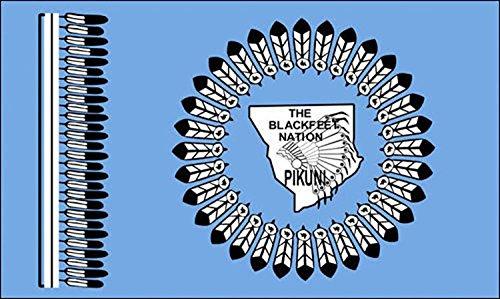

Blackfeet Flags

The Blackfeet Flag

The Blackfeed Nation flag, which is not used extensively, is a medium blue and bears at the hoist a ceremonial lance or coup stick, having 29 eagle feathers attached.

In the center is a ring of 32 white and black eagle feathers surrounding a map of the reservation. On this appears a warbonnet and the name of the tribe in English and in the Algonquin based native tongue of the Blackfeet. All items appearing in the center are white with black edging and black lettering.

Flag of the Siksika Nation

The Siksika flag of Alberta, Canada incorporates the tribal emblem, along with the Union Jack flag on a white background. An alternate version of the flag has a red background with the tribal emblem and the Union Jack is cropped into a tipi shape.

In the Siksika flag, the buffalo in the Coat was chosen as the symbolic animal of the Siksika because it provided their ancestors with food, clothing and shelter; the arrow in seven pieces represents the seven sacred religious societies in the tribe.

The medicine pipe symbolizes peace and crosses the tomahawk, the weapon of war which was put to rest forever; the circles represent the duration of the treaty signed by Chief Crowfoot on September 22, 1877; as long as the sun shines, the grass grows and the water flows.

Blackfoot History

Niitsítapi, the Blackfoot people, have a long and rich history on the Northern Plains. According to tribal elders, the people have always lived on the Plains, since the time when muskrat brought up the mud from under the waters.

Archaeologists can trace the Blackfoot through their artifacts and sites for at least a thousand years. Beyond that, archaeologists are reluctant to put a tribal name on the earlier tools and sites.

The archaeologists say the Blackfoot were members of an American Indian people who migrated from the Great Lakes north and west into the Saskatchewan River valley, Canada, and Montana, in the early 1700s.

Aboriginal people have lived on the Plains of southern Alberta for at least 11,000 years.

The Blackfeet first aquired horses in 1730, which they called “elk dogs” because of their large size. Prior to this time, they used dogs as a pack animal to pull their travois. The Blackfoot were first introduced to horses when the Shoshoni attacked them on horseback.

The Blackfeet were renowned for their horse riding skills, and maintained large herds of horses. Stealing enemy horses gave a warrior prestige.

They also developed their own breed of sturdy Blackfeet Buffalo Horse.

In 1895 the Blackfeet tribe sold what is now Glacier National Park to the U.S. government for mineral exploration.

Blackfeet Subsistance

Traditionally, the Blackfoot had a way of life centered around buffalo hunting. They were skilled buffalo hunters even before they acquired horses and guns in the 18th century, and had a warrior culture.

Buffalo and other big game provided nearly all their basic needs, including food, clothing, and tepee covers. The Sitsika wore leather clothing made primarily from the skins of deer, elk and buffalo. A buffalo robe or trade blanket was added in winter.

The Sitsika were a nomadic people who followed a seasonal round. For almost half the year, these Blackfoot bands lived in winter camps.

The bands were strung out along a wooded river valley, perhaps a day’s march apart; in areas with adequate wood and game resources. Some bands might camp together all winter.

From about November to March, the people would not move camp unless food supplies, firewood or pasture for the horses became depleted.

In spring the bison moved out onto the Plains where the new spring grasses provided forage. The people might not follow immediately for fear of spring snowstorms.

During this time they might have to live on dry food or game animals such as deer. Soon, however, the bands would leave to hunt the buffalo. During this time each band traveled separately.

After the Sun Dance, the bands again separated to pursue the buffalo.

Other important rituals included the sweat lodge and buffalo tongue ceremonies. All major ceremonies were presided over by an elderly medicine woman.

In the fall, the bands would gradually shift to their wintering areas and prepare the bison jumps and pounds. Several bands might join together at particularly good sites, such as Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump.

As the bison moved into the area, drawn by water and richer forage than the burned-dry summer grasses, communal kills would again occur, and the people would prepare dry meat and pemmican for winter.

Such dry food stores were used as emergency supplies for those times when the bison were not near. At the end of the fall, the Blackfoot would again move to their winter camp locales.

The Blackfeet had a cohesive political structure, and consultations between the chiefs took place on any matters affecting the Blackfeet as a whole.

The Blackfeet originally hunted buffalo on foot, using bows and arrows, but were introduced to horses by the Shoshone, who attacked them on horseback in 1730.

They soon obtained their own horses through trade with the Salish and Nez Percé, and acquired guns in 1780.

Blackfoot tipis used a four pole frame, while many other Plains tribes used a three pole frame.

Prior to the acquisition of the horse in 1730, the only domesticated animal used by the Blackfoot was the dog.

Dogs were used to pull a travois carrying some of their belongings, which is a platform lashed to two poles, which would be strapped to the sides of the animal and dragged behind it.

By the time the Blackfeet established their extensive territory in the northwest region, they were organized as a loose confederacy of three politically independent tribes, comprising a southern division called the PEIGAN (Pikuni or Scabby Robes) now living in Montana, a central division called the Bloods (Kainai, or Many Chiefs) and the North Blackfeet (Siksika or Blackfoot). Each band was led by a Blackfeet Chief. The two latter tribes now reside on reserves in the province of Alberta Canada. These three tribes shared a common culture, spoke the same language, held a common territory and made war on each other’s enemies.

Blackfoot Catastrophes

Smallpox epidemic of 1760.

In 1781 the Blackfeet suffered severely from smallpox, and their numbers dwindled from an estimated 15,000 to about 6,000.

Smallpox epidemic of 1794.

The Blackfeet Indians continued to control the northern Great Plains and prevented white settlement in their territory until their hold was loosened by another devastating smallpox epidemic in 1837 that killed two thirds of the population. Approximately another 6,000 Blackfeet died in this epidemic.

Smallpox epidemic of 1839.

In 1855 their territory was defined by treaty with the US government.

Smallpox epidemic of 1869.

Starvation year of 1882 when the last buffalo hunt failed. Thousands more starved to death after the buffalo herds were wiped out by the Europeans.

White settlement in Blackfoot Country

White settlement and the near extinction of the buffalo in the 1880s ended their nomadic lifestyle.

White settlement began in Blackfoot country in 1860, and in 1865 fighting broke out with the settlers.

In 1870, 200 Piegan Blackfoot, including women and children, were killed in the Marias Massacre, an unprovoked attack on a friendly camp by the US army who were hunting a hostile party.

By the 1870s commercial buffalo hunting had drastically reduced the Blackfeet’s staple food. Although the 1882 winter buffalo hunt was successful, as prairie fires had driven northern herds into Montana, in the winter of 1883–84 the buffalo suddenly disappeared and over 600 Blackfeet died of starvation.

Survivors were forced to give up their hunting lifestyle and take up farming. Between 1907 and 1912 their US reservation lands were divided into allotments, with individuals receiving 140 ha/350 acres.

Most now farm their respective reservation allotments.

Most Blackfeet now live on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana and Blackfeet reservations in Alberta, Canada. They number about 27,100 (as of 2000) in the USA, and 15,000 in Alberta, Canada.

Blackfoot Culture

The basic social unit of the Blackfoot, above the family, was the band. Bands among the Peigan varied from about 10 to 30 lodges, or about 80 to 240 persons.

Such bands were large enough to defend themselves against attack and to undertake small communal hunts.

The band was a residential group rather than a kin group; it consisted of a respected leader, possibly his brothers and parents, and others who need not be related.

A person could leave a band and freely join another. Thus, disputes could be settled easily by simply moving to another band. As well, should a band fall upon hard times due to the loss of its leader or a failure in hunting, its members could split-up and join other bands.

The system maximized flexibility and was an ideal organization for a hunting people on the Northwestern Plains.

Leadership of a band was based on consensus; that is, the leader was chosen because all people recognized his qualities. Such a leader lacked coercive authority over his followers; he led only so long as his followers were willing to be led by him.

A leader needed to be a good warrior, but, most importantly, he had to be generous. The Blackfoot despised a miser!

Upon the death of a leader, if there was no one to replace him, the band might break up. Bands were constantly forming and breaking-up.

Blackfoot Religion and Ceremonies

Spiritual beliefs and ceremonies were an important part of the Blackfoot culture. Plains Indian culture was steeped in religion and ceremony. The world was an uncertain place, and people needed the help of supernatural powers.

The principle deity is most often referred to as “Old Man.”

Help was obtained from the spirit world in the form of visions and dreams. In these dreams people were instructed in the use of sacred objects, songs and rituals.

It was the adolescent warrior who attempted the vision quest by going to a remote area and fasting until he had a vision.

He would be given a war song or dance by a guardian spirit and be told of the magical amulets (such as feathers, birds’ beaks, or stones) that should be worn to give him power.

Most failed and did not have a vision, in which case they would buy a bundle and its ritual.

Individual bundles acquired much respect and gave its owner prestige, especially those associated with war such as headdresses and shields.

These objects and rituals became part of their sacred Medicine Bundles.

Medicine Bundles were the most powerful religious possession in Plains Indian culture. They were owned by individuals but could bring power, luck or health to anyone who honoured them.

Ownership of a bundle brought long life, success and social prestige.There were different kinds of medicine bundles, each symbolizing different kinds of power.

The Medicine Pipe was given to the people by Thunder. A Medicine Bundle would contain a sacred pipe, the skins of muskrat, mink, otter, squirrel, owl and other birds, a rattle, a wooden bowl, and several small rawhide bags containing red earth paint, pine needle incense for smudges, and tobacco.

The bundle would be opened at least once a year, shortly after the first thunder in the spring.The hollow bones from large birds, such as geese and eagles, were sometimes made into whistles used in sacred and healing ceremonies.

In mid-summer, when the Saskatoon (Service) berries were ripe, the bands came together for the Sun Dance. The Sun Dance was the major tribal ceremony in historic times. Such tribal ceremonies are described as Rites of Intensification because they serve the social purpose of binding the loosely organized tribal bands together.

Communal hunts of bison provided food for the gathering and the bulls’ tongues were necessary as offerings at the ceremony. This was the only time of year when all the people of the tribe assembled at the same place.

Another important ceremony was the Medicine Lodge Ceremony.

Napi is a Blackfoot Culture Hero who transformed the world for the people.Traditionally, the Indian nations of the Northern Plains, such as the Blackfoot, were egalitarian societies.

The Blackfoot creation story takes place directly below Glacier National Park in an area that is referred to as the ‘Badger-Two Medicine.’

Chief Mountain above Browning, Montana is a Blackfeet sacred mountain.

Within Blackfoot society, there were no individuals, no groups of people, who were endowed by a god, creator, or other entity with any more rights than anyone else.

As animists, they also viewed all other living things as people, as having souls.

Within their egalitarian world-view, all people (human people, animal people, bird people, plant people, and stone people) were seen as equals.

Humans did not have superior rights, they did not have dominion over the rest of creation. Humans tried to live in harmony with nature.

Societies:

During the summer when the bands assembled for tribal ceremonies and hunting, the warrior societies would become active. These societies, known as Pan-tribal Sodalities, are a very interesting social institution. Membership was not based on kinship ties. Membership crosscut the bands and was purchased.

A number of young men would purchase membership in the lowest society. Throughout their lives, they would continue to purchase membership in higher societies while selling their old positions to the new generation. These warrior societies acted as a police force, regulating camp moves and the communal hunt.

Religious Societies:

-

- Black Soldier

- Brave Dog

- Crow

- Horn

- Ma’tsiyiiks

- Motoki

- Prairie Chicken

Blackfeet Culture and Trade

Blackfoot culture centered around hunting the buffalo. Every part of this animal was put to use in their daily life, and was their main protein source for food.

One way they hunted the buffalo, more correctly called prairie bison, was to drive them off a cliff at a place known as the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, located in what is now Alberta, Canada.

Today, there is a unique 7 story interpretive center concealed in the face of the cliff, which tells the story of the Blackfoot, the buffalo, and the buffalo jump. It is well worth a visit if you are in the area.

In the late 1700s, Europeans began to arrive on the Northern Plains in Alberta, Canada and their arrival brought a century of great cultural change to the First Nations of the region.

During this century, the buffalo, which had provided the Indians with food and shelter, came close to extinction.The coming of the fur trade also had a far reaching impact on the people.

One of the first traders to reach the Blackfoot was Peter Fidler who came among them in 1792. While he may have been the first European trader to reach the Blackfoot, European trade goods such as metal items, beads, cloth, and guns, had reached them several decades earlier.

The traders not only brought in European trade goods, but more importantly they involved the Indians in a globalized economic system.

The most famous trade good developed by Hudson’s Bay Company was the blanket. By 1740, the Hudson’s Bay Company was making a specially designed trade blanket. These blankets were heavier than other trade blankets and were made of pure wool.

Each blanket was assigned a certain number of “points” based on its weight, and a series of stripes indicating the “points” were woven into the blankets.

In this way the trade value of the blanket was easily seen by both trader and the Indian fur trappers.

Blackfeet Indian Crafts:

Best known for basket making, quillwork, and later beadwork, the shaping of wooden utensils and bowls and an all but forgotten tradition of pottery making ties their origin with Eastern Woodland Indians.

Article Index:

A debate over whether to expand the eligibility requirements to enroll as a Blackfeet tribal member is dividing the Blackfeet Nation.

The Blackfeet tribe in 2011 had 16,924 enrolled members, according to tribal enrollment office statistics. But there are about 105,000 people who identified themselves as `Blackfeet Indian’ on the 2010 U.S. Census.

The Blackfeet’s original constitution, written in 1935, included a requirement that tribal members be at least 1/16th Blackfeet. The constitution was amended in 1962 to raise that requirement to a quarter.

The Blackfeet’s original constitution, written in 1935, included a requirement that tribal members be at least 1/16th Blackfeet. The constitution was amended in 1962 to raise that requirement to a quarter.

All Blackfeet children living on the reservation prior to Aug, 30, 1962, were also included as tribal members. But in some cases their children do not meet the blood quantum requirement and are excluded from tribal rolls.

For the past 50 years, Blackfeet tribal eligibility has been determined by whether a person is at least one-quarter Blackfeet, meaning that at least one grandparent must be a full-blooded Blackfeet. A majority of federally recognized tribes use that measure, known as blood quantum, to determine eligibility, according to the Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission.

But an organization called Blackfeet Enrollment Amendment Reform is collecting signatures for a petition seeking to change that standard. Its members want enrollment eligibility to include anyone who has proof of being the child, grandchild or great-grandchild of an enrolled tribal member.

Supporters say the change would lead to more tribal inclusion and unity.

Those opposed to the proposed lineal descent eligibility include members of the Blackfeet Against Open Enrollment movement, who say blood quantum separates those with a close affiliation to Native American life and cultural values from others with little or no personal connection to their ancestral heritage.

Robert Hall’s parents are enrolled members but with a 15/64 blood quantum, he is not. He grew up on the reservation, speaks the Blackfeet language and identifies with Blackfeet cultural values.

Hall told the Great Falls Tribune that he believes blood quantum system is racist.

“We are literally living in a caste system – people with certain genetic qualities who are denied access to resources because of their racial makeup. If any other group in America was advocating this type of racial purity, they would be condemned as racists,” Hall said.

Opponents of the proposed change are angered by racism allegations, saying those advocates are in effect campaigning to assimilate the Blackfeet people into white culture. Within a few generations, the cultural and ethnic characteristics that make the Blackfeet people unique would be lost by expanding enrollment, they said.

“When we go back and we look through history, Indians have fought assimilation and we have won – and we’re still winning today,” said Nathan DeRoche, an enrolled tribal member and an opponent of expanded enrollment. “But if we open that enrollment, they have won. Then we are a defeated people.”

Enrollment in the Blackfeet Tribe is governed by Ordinance 14. (This link is a PDF file. You will need the Adobe Acrobat Reader to print and view this file. If you do not have the Adobe Acrobat Reader, you can download it for free here.)

Each Indian tribe had their own word to mean the Blackfoot Tribe. Here is a list of a few of the names given the Blackfoot by other Indian tribes: