Famous Kiowa

Famous Kiowa Chiefs and Leaders

Adoeette (ado ‘tree,’ e-et ‘great,’ te personal suffix: ‘Big Tree’) – A Kiowa chief, born about 1845.

Ahpeahtone (1856–1931) – chief

Tristan Ahtone (b. 1981) – Award winning journalist.

Richard Aitson (b. 1953) – bead artist and poet.

Spencer Asah – Painter, one of the Kiowa Six.

James Auchiah – Painter, one of the Kiowa Six.

Big Bow, (1833–ca. 1900) – War chief.

Michael C. Satoe Brown (b. 1961) – Contemporary painter.

T. C. Cannon – Painter and printmaker.

Jesse Ed Davis (1944–1988), Kiowa–Muscogee Creek–Seminole guitarist.

Dohasan (Dohásän, ‘little bluff’; also Dohá, Doháte, ‘bluff’) – The hereditary name of a line of chiefs of the Kiowa for nearly a century. It has been borne by at least four members of the family:

The first of whom there is remembrance was originally called Pá-do‛gâ′-i or Padó‛gå, ‘White-faced-buffalo-bull’, and this name was afterward changed to Dohá, or Doháte. He was a prominent chief.

His son was originally called Ä′anoñ′te (a word of doubtful etymology), and afterward took his father’s name of Doháte, which was changed to Dohasan, Little Doháte, or Little-bluff, for distinction.

He became a great chief, ruling over the whole tribe from 1833 until his death on Cimarron River in 1866, since which time no one has had unquestioned allegiance in the tribe. His portrait was painted in 1834 by Catlin, who calls him Teh-toot-sah, and his name appears in the treaty of 1837 as ”To-ho-sa, the Top of the Mountain.”

His son, whose widow is Ankímä, inherited his father’s name, Dohásän. He was also a distinguished warrior, and died about 1894. His scalp shirt and war-bonnet case are in the National Museum. Dohasan II, the greatest chief in the history of the Kiowa tribe, in 1833 succeeded A‛dáte, who had been deposed for having allowed his people to be surprised and massacred by the Osage in that year.

It was chiefly through his influence that peace was made between the Kiowa and Osage after the massacre referred to, which has never been broken.

In 1862, when the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, and Kiowa Apache were assembled on Arkansas River to receive annuities, the agent threatened them with punishment if they did not cease their raids.

Dohasan listened in perfect silence to the end, when he sprang to his feet, and calling the attention of the agent to the hundreds of tipis in the valley below, gave a famous speech.

In addition to the treaty of 1837 Dohasan was also a signer of the treaty of Ft Atkinson, Ind. T., July 27, 1853, and treaty of October 18, 1865, on Little Arkansas River, Kansas.

The nephew of the great Dohásän II and cousin of the last mentioned was also called Dohásän, and always wore a silver cross with the name “Tohasan” engraved upon it. He was the author of the Scott calendar and died in 1892.

Shortly before his death he changed his name to Dánpä′ , shoulder-blade, from dán, shoulder (?), leaving only Ankímä’s husband to bear the hereditary name, which is now extinct.

Drum Groups: Prominent contemporary powwow drums led by Kiowa singers include: Cozad Singers, (NAMMY winners), Bad Medicine Singers , Zotigh Singers , and Thunder Hill Singers. All four drum groups have won the prestigious Gathering of Nations Southern Challenge.

Teri Greeves (b. 1970) – Bead artist.

Sharron Ahtone Harjo (b. 1945) – Painter, ledger artist.

Jack Hokeah – Painter, one of the Kiowa Six.

Vanessa Paukeigope Jennings (b. 1952) – Bead artist, clothing and regalia maker.

Kicking Bird (1835–1875) – War chief.

Kiowa Six – A group of six famous Kiowa artists from Oklahoma in the 20th century.

Lone Wolf (Gui-pah-gho), The Elder – A Kiowa Principal Chief, one of the 9 signers of the treaty of Medicine Lodge, Kansas in 1867, by which the Kiowa first agreed to be placed on a reservation. In 1872 he headed a delegation to Washington.

The killing of his son by the Texans in 1873 embittered him against the whites, and in the outbreak of the following year he was the recognized leader of the hostile part of the tribe. On the surrender in the spring of 1875 he and a number of others was sent to military confinement at Ft. Marion, Florida, where they remained 3 years.

He died in 1879, shortly after his return, and was succeeded by his adopted son, of the same name.

Tom Mauchahty-Ware – Kiowa-Comanche flutist and dancer.

Parker McKenzie (1897–1999) – Traditionalist and linguist.

Arvo Quoetone Mikkanen (born April 1961) – An Assistant United States Attorney in the Office of the United States Attorney for the Western District of Oklahoma and a former federal judicial nominee for the United States District Court for the Northern District of Oklahoma.

N. Scott Momaday – Poet and novelist. In 1969, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his first novel, The Way to Rainy Mountain (1968). Momaday’s writing is filled with stories about himself and his people, the Kiowa, especially his first book, and in his works called The Gourd Dancer (1976), The Names (Sun Tracks) (1976), The Ancient Child (1989), and In the Presence of the Sun: A Gathering of Shields (1992).

Stephen Mopope – Painter, one of the Kiowa Six.

Betty Nixon – Co-founder of the Mid-America All-Indian Center.

Cornel Pewewardy (flutist Comanche/Kiowa) is a leading performer of Kiowa/Southern Plains music, including Kiowa Christian hymns which include prominent glissandos.

Horace Poolaw (1906–1984) – Photographer

Sleeping Wolf – Sleeping wolf (proper name Gui-k̉ ati, ‘Wolf lying down’). Second chief of the Kiowa, a delegate to Washington in 2872 , and a prominent leader in the outbreak of 1874-75. He was shot and killed in a quarrel with one of his own tribe in 1877. The name is hereditary in the tribe and has been borne by at least 5 successive individuals, the first of whom negotiated the permanent peace between the Kiowa and Comanche about 1790.

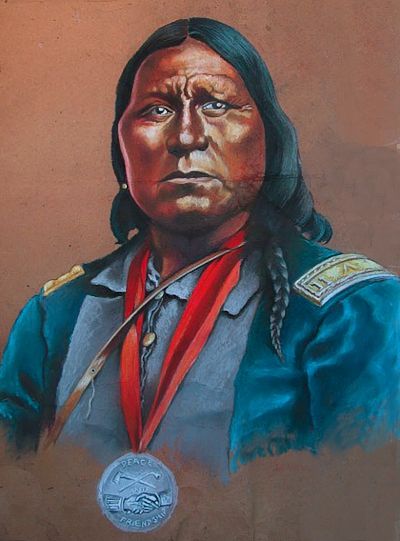

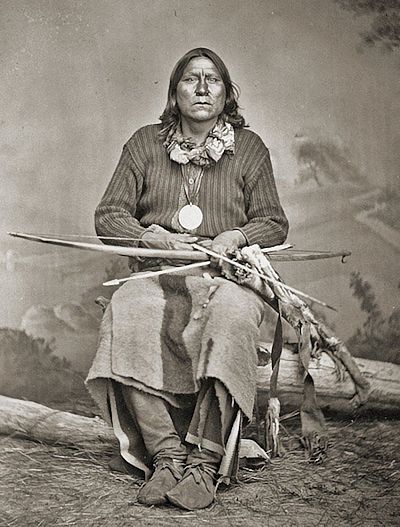

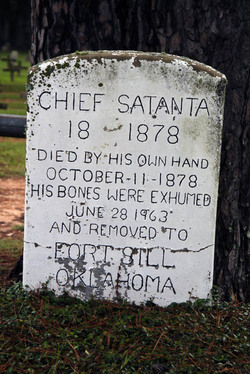

Satanta (properly Set-taiñ’-te, ‘White Bear’) – The most famous Kiowa chief, born about 1830; died in prison, Oct. 11, 1878. For about 15 years before his death he was recognized as second chief in his tribe, the first rank being accorded to his senior, Setängyä, or Satank, and later to Lone Wolf, although probably neither of these equaled him in force and ability.

His eloquence in council gained for him the title of “Orator of the Plains,” while his boldness and directness and keen humor made him a favorite with army officers and commissioners in spite of his known hostility to the white man’s laws and civilization.

He was one of the signers of the Medicine Lodge treaty of 1867, by which his tribe agreed to go on a reservation, his being the second Kiowa name attached to the document.

The tribe, however, delayed coming in until compelled by Custer, who seized Satanta and Lone Wolf as hostages for the fulfillment of the conditions.

For boastfully avowing his part in a murderous raid into Texas in 1871, he, with Setangya and Big Tree, was arrested and held for trial in Texas. Setangya was killed while resisting the guard.

The other two were tried and sentenced to life imprisonment in the Texas State penitentiary. Two years later they were released, conditional upon the good behavior of their people, but in the fall of 1874, the Kiowa having again gone on the warpath, Satanta was rearrested and taken back to the penitentiary where he finally committed suicide (or died trying to escape) by throwing himself from an upper story of the penitentiary hospital.

Quotes from Kiowa Chief Santana

Set’aide (White Bear) – Prominent war chief in the 1800s.

Setangya (Set-äbgyä, ‘Sitting Bear’) – A noted Kiowa chief and medicine man, and leader of the principal war society of the tribe. commonly known to the whites as Satank. He was born in the Black Hills region about the year 1810, his paternal grandmother having been a Sarsi woman.

He became prominent at an early age, and is credited with having been a principal agent in negotiating the final peace between the Kiowa and the Cheyenne about 1840. His name heads the list of signers of the noted Medicine Lodge treaty of 1867.

In 1870 his son was killed by the whites while raiding in Texas. The father went down into Texas, gathered the bones into a bundle and brought them back, carrying them about with him upon a special horse until himself was killed about a year later. On May 17, 1871, in company with Settainte he led an attack on a wagon train in Texas, by which 7 white men lost their lives.

On making public boast of the deed to the agent at Ft Sill, in the present Oklahoma, shortly afterward, he and two others were arrested by military authority to be sent to Texas for trial.

Setangya, however, refused to be a prisoner, and deliberately inviting death, sang his own death song, wrenched the fetters from his wrists, and drawing a concealed knife sprang upon the guard and was shot to death by the troops surrounding him. He was buried in the military cemetery at Ft Sill.

Sitting Bear (Set-Tank, Set-Angia, Setangya, also called Satank) (ca. 1800—1871) – Kiowa War chief and medicine man, participated in the Warren Wagon Train Raid.

Silver Horn (1860–1940) – Artist and calendar keeper.

Lois Smoky – Bead artist and painter, one of the Kiowa Six.

Monroe Tsatoke – Painter, one of the Kiowa Six.

Terry Tsotigh – Flutist.

Tsau lau te (Cry of the Wild Goose) – Son of Chief Satanta, Kiowa

Red Warbonnet (d. 1849) – Traditionalist.

White Horse (Tsen-tainte) (d. 1892) – chief

Chris Wondolowski – US professional soccer player.

Kiowa Tribes:

Article Index:

Dohasan is the hereditary name of a line of chiefs of the Kiowa for nearly a century. It has been borne by at least four members of the family.

The first of whom there is remembrance was originally called Pá-do‛gâ′-i or Padó‛gå, ‘White-faced-buffalo-bull’, and this name was afterward changed to Dohá, or Doháte. He was a prominent chief.

Lone Wolf the Younger (Mamadayte)

Born 1843, Oklahoma, USA – Died Aug. 11, 1923, Hobart, Kiowa Co, Oklahoma

Wife: Akeiquodle (1850 – 1938)

Daughter: Sarah Ahtape Lone Wolf Kauahquo (1886 – 1958)

Lone Wolf was appointed Chief of the Kiowa in 1883 and served 40 years until his death in 1923. Prior to becoming chief, he was a fierce warrior named Mamadayte who survived the Battle of Washita, in which General Custer surprised and overcame Black Kettle, Chief of the Cheyenne.

On Dec 23 1873, the only son of Chief Lone Wolf the Elder, 19 year old Tau-Ah-Kia, was killed in South Texas. Riding iwith him at Mitchell Co. Texas was a boyhood friend, Mo-ma-day who retrieved his fallen friend, Tau-Ah-Kia, and buried him according to Kiowa Custom.

On Dec 23 1873, the only son of Chief Lone Wolf the Elder, 19 year old Tau-Ah-Kia, was killed in South Texas. Riding iwith him at Mitchell Co. Texas was a boyhood friend, Mo-ma-day who retrieved his fallen friend, Tau-Ah-Kia, and buried him according to Kiowa Custom.

In 1874 in Greer County, Lone Wolf II, with a band of Comanche warriors, fought Major William’s men under command of Col. G. F. Buel, in his last battle with the United States. Auxiliary chiefs were Gotebo, Komalty, Ahtape, and Spotted Bird.

In 1879, he was adopted by the elder Chief Lone Wolf based on his bravery in battle. The town of Lone Wolf, Texas in Mitchell Co. Texas is named after Lone Wolf I (GUI-PAH-GO). The town of Lone Wolf, Oklahoma is named after Lone Wolf II (MO-MA-DAY).

Chief Lone Wolf I was a signer of Treaty of Little Arkansas. QUO-PAH-KO, which is engraved on the younger Lone Wolf’s gravestone, refers to the band of Kiowa Indians who were present for the signing of this treaty.

Chief Lone Wolf I was a signer of Treaty of Little Arkansas. QUO-PAH-KO, which is engraved on the younger Lone Wolf’s gravestone, refers to the band of Kiowa Indians who were present for the signing of this treaty.

Lone Wolf I died of malaria the same year and lies buried in an unmarked grave on the north side of Long Horn Mountain east of Kiowa County, Oklahoma.

In boyhood Lone Wolf II saw U. S. soldiers forbid the Sundance and the Kiowa warriors withdrawn from the banks of the Wichita River. Their medicine lodge was deserted and their sacred Sundance tree left standing alone. That aborted Sundance held in 1884 is still known to the Kiowas as “The day the forked poles were left standing.” The Chief saw a way of life end and a new way of life beginning to take root.

In 1901, while serving as the Kiowa Chief, he filed a lawsuit on behalf of several tribes, opposing opening Indian Territory to white settlement. In his suit filed at El Reno , Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock 187 US 553 (1903), which was decided by the Supreme Court. He charged that Native American tribes were being defrauded of their land by acts of Congress, in violation of the Medicine Lodge Treaty. Clinton F. Ervin, Judge of the Territorial Federal court tore up the application and denied the request of the Kiowa Chief.

In 1901, while serving as the Kiowa Chief, he filed a lawsuit on behalf of several tribes, opposing opening Indian Territory to white settlement. In his suit filed at El Reno , Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock 187 US 553 (1903), which was decided by the Supreme Court. He charged that Native American tribes were being defrauded of their land by acts of Congress, in violation of the Medicine Lodge Treaty. Clinton F. Ervin, Judge of the Territorial Federal court tore up the application and denied the request of the Kiowa Chief.

Lone Wolf then made a trip to Washington, D.C. to see President McKinley hoping to stop the opening of the lottery, but the president declined to intervene. The Kiowas were given one hundred sixty acre allotments along the Elk Creek bottom lands. He saw his domain that originally covered Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas and parts of Old Mexico shrink to a mere 160 acre allotment.

Even though he lost the law suit, a landmark case, he led his people in adapting peacefully to the white man’s culture. He was the last of the recognized chiefs of the Kiowa. After his death there were no real chiefs.

The Democrat newspaper in Chief Hobart, Oklahoma published Lone Wolf II’s obituary in 1923, giving the details of his death at age 76.

Satanta’s (often misspelled as Santana) name actually was Set-tainte, which means White Bear Person. One of the leading Kiowa chiefs in the 1860s and ’70s, Satanta was a fearsome warrior, but also a skilled orator and diplomat. Satanta negotiated numerous times with the American government and signed such treaties as the Little Arkansas (1865) and Medicine Lodge (1867). He fought a protracted war to protect his tribe’s land before settlers, miners and others finally overwhelmed it.

Birth of Satanta

Satanta was born in 1830, somewhere on Kiowa lands, probably in what is now Kansas or Oklahoma. He was the son of Red Tepee, keeper of the Tai-me (Kiowa medicine bundles). Those days were the zenith of Plains Indianpower and cultural flowering ~ez_mdash~ the last of the free days.

Satanta was born in 1830, somewhere on Kiowa lands, probably in what is now Kansas or Oklahoma. He was the son of Red Tepee, keeper of the Tai-me (Kiowa medicine bundles). Those days were the zenith of Plains Indianpower and cultural flowering ~ez_mdash~ the last of the free days.

During his boyhood, Satanta was called Guatonbain (Big Ribs).

Death of the buffalo, and demise of the free Plains Indians

The buffalo supplied food, clothing, and hides for the Kiowa teepees. For untold generations, the Plains natives had hunted the tatonka, taking just enough animals to live.

With the white man’s invasion, settlers crossed Kiowa lands unrestricted and indiscriminately killed the bison. They hunted the buffalo just for their hides, killing entire herds and leaving vast areas of grassland littered with the rotting flesh of hundreds of animals. The slaughter also served as a weapon against the Plains Indians, used by the government and military, to starve them into submission as a first step toward the near-genocide and subjugation of a free people.

In the 1860s and 1870s, the Kiowa waged ongoing resistance to protect their land and way of life. Even as they sought peace at the treaty table, white soldiers went out and slaughtered the buffalo for sport.

The fate of the Plains natives, whether they were Lakota (Sioux), Arapaho, Comanche, or Kiowa, was the same. The white soldiers increasingly swept them up and relegated them to small, hardscrabble reservations. The government tried to ensure that the Indians would remain on the worthless land by increasingly killing off the remaining buffalo and forcing the proud Indian nations to become dependent on government handouts.

Satanta’s early career

Satanta was entrusted with a war shield when he was still a young man, which he used while raiding in Texas and Mexico. Satanta did his best to stem the loss of life, freedom, and sovereignty of his Kiowa brethren, and proved willing to use diplomacy. When negotiating with the Europeans did not work, he was not afraid to use warfare as means to secure his ends. During the early days of the Civil War, Satanta conducted numerous raids along the Santa Fe Trail.

He developed a reputation as an outstanding warrior, and in his twenties, became a chief. Promotion to the position took place according to the traditional values of the warrior nations: courage in battle and deep-seated devotion to the Kiowa nation. Satanta led his Kiowa warriors in raids on the Cheyenne and Ute nations, even extending his forays into Texas and Mexico.

By the 1860s, Satanta, like Chief Lone Wolf (Guipago) and Chief Kicking Bird (Teneangope), had risen to a position of leadership among the Kiowa. At that time, the principal Kiowa chief was Chief Dohäsan (Little Mountain). In 1865, Satanta participated, along with those men, in the negotiations that led to the Treaty of the Little Arkansas River. Like most treaties of its type, the agreement failed to ensure peace on the frontier. The Native Americans viewed that treaty, like all the treaties with the soldiers, as just another attempt to pacify Native Americans while continuing to appropriate their lands.

At the time, General William T. Sherman was commander of the U.S. forces in the West; he detested the Indians and treated them accordingly. His field subordinates were General Philip Sheridan and Lt. Colonel George A. Custer.

The raids that Satanta led, in response to the army’s predations and the federal government~ez_rsquo~s actions, won him even more recognition. The wasichu continued to flood across Kiowa lands, and tribesmen, unhappy with the provision that reduced their domain to a small reservation, continued to raid settlements and harass settlers.

Satanta competes to replace principle chief Dohäsan

The unstable situation worsened significantly with Dohäsan’s death in 1866. He had been a strong chief and maintained the closeness of the Kiowa clans for many years. With Dohäsan gone, Kiowa unity dissolved. Several subchiefs competed to fill the void, including Satanta, who favored armed resistance, Chief Lone Wolf (Guipago) and Chief Kicking Bird (Tene-angopte) who favored peace. Their fierce competition to prove who would best replace Chief Dohäsan, set off a wave of raids against the U.S. Army and white settlers across the southern plains during the fall of 1866 and into 1867.

The unstable situation worsened significantly with Dohäsan’s death in 1866. He had been a strong chief and maintained the closeness of the Kiowa clans for many years. With Dohäsan gone, Kiowa unity dissolved. Several subchiefs competed to fill the void, including Satanta, who favored armed resistance, Chief Lone Wolf (Guipago) and Chief Kicking Bird (Tene-angopte) who favored peace. Their fierce competition to prove who would best replace Chief Dohäsan, set off a wave of raids against the U.S. Army and white settlers across the southern plains during the fall of 1866 and into 1867.

Satanta’s exploits gained him prestige, and he was made one of the tribe’s representatives at the Medicine Lodge Treaty council in October 1867. The area called Medicine Lodge was located in Kansas, where the Medicine River and Elm Creek join.

More than 5,000 Indians – Kiowa, Comanche, Kiowa Apache, Cheyenne, and Arapaho – attended the meeting. The 7th Calvary was on hand to protect the white negotiators. Although Satanta agreed that Kiowas should live on reservations, the natives delayed the relocation, so Colonel Custer kept Satanta as a hostage until the tribe completed the move.

The treaty was signed in October, but did not last. As the deluge of settlers into their lands continued, the Kiowa resumed their raids. General Sheridan was ordered to devise a plan to break the Kiowas’ will. Sheridan’s winter campaign of persecution in 1868-1869 was brutal and bloody. The U.S. military under Colonel Custer not only killed warriors, but also women and children, and destroyed native horses and homes.

Demoralized by Custer’s indiscriminate tactics, Satanta and Guipago decided to surrender. The two chiefs approached the colonel on December 17, under a flag of truce, to discuss surrender. Custer ignored the truce and arrested the two chiefs. For the following three months, Custer tried to get permission to hang them. In early 1869, they were freed, owing to the efforts of Tene-angopte, who promised that the Kiowa would quit raiding and return to the reservation.

In 1871, Satanta, with assistance from Chief Big Tree (Adoeete) and Chief Satank (Sitting Bear), led a large party of Kiowas off the reservation, then joined forces with a Comanche party, ostensibly to hunt buffalo in Texas. They spotted a wagon train traveling along the Butterfield Trail. Hoping to steal guns and ammunition, the warriors attacked the 10 freight trains and killed seven teamsters. The warriors let the remaining drivers escape while they looted the wagons.

Upon their return to the reservation, the Indian agent, informed about the Texas raid, asked if any of his Indians had participated. Amazingly, Satanta announced that he had led the raid, and that their poor treatment on the reservation justified it. Shocked, the agent turned them over to General Sheridan, who sent the three chiefs to Jacksboro, Texas, on June 8, 1871. They would stand trial for murder.

On the way to Jacksboro, Satank, an elder of the Koitsenko and Crazy Dog warrior societies, was killed while attacking a guard. Satanta and Adoeete were convicted of murder and sentenced to hang. At his trial, Satanta warned what might happen if he were hanged. Edmund J. Davis, governor of Texas, fearful that the Kiowa would never let the death of Satanta go unanswered, commuted his and Adoette’s sentences to life imprisonment.

Transferred to the prison at Huntsville, Texas, Satanta and Adoeete remained there for two years. Following their conviction, government agents promised the Kiowa people that if they played good Indian, the two would be released. For two years, the Kiowa remained on the reservation and caused no problems. Governor Davis, pressured by federal agents to parole Chief Satanta and Adoeete, released them on August 19, 1873.

In response to perceived maltreatment by the government and its agents, the Kiowa and Comanche resumed their armed resistance. Settlers in Oklahoma and the Texas panhandle fell under constant harassment by those armed parties as the Kiowa and Comanche tried to stop the slaughter of the tatonka (Buffalo).

Satanta’s Latter Days

Like all early Native Americans, Satanta witnessed and lived through the defeat and near-extermination of the Native American way of life, and the imprisonment on reservations at the hands of the white man.

Like all early Native Americans, Satanta witnessed and lived through the defeat and near-extermination of the Native American way of life, and the imprisonment on reservations at the hands of the white man.

After he removed himself as war chief, owing to age and health problems, Satanta’s council continued to be viable. Even in retirement, Satanta was often present to assist during attacks by federal soldiers. Satanta, along with Chief Adoeete, was again taken into custody and imprisoned for violating their parole.

Chief Adoeete was held in the guardhouse at Fort Sill while Chief Satanta was returned to the Huntsville State Prison on September 17, 1874. Satanta never again stepped out of that prison.

He died on October 11, 1878, in an escape attempt, by jumping out of a second-story window of the prison hospital. He was interred in the prison cemetery until 1963, when permission was granted to remove his remains and rebury them at Fort Sill, next to his friend and wartime companion Satank.