Jackson Sundown, a nephew of Chief Joseph, was with him on the flight of the Nez Perce in 1877. He was the first native American to win a World Championship Bronc Rider title in 1916, at the age of 53, more than twice the age of the other competitors who made it to the final round. He is also the oldest person to ever win a rodeo world championship title. He was posthumously inducted into the Pendleton Round-Up Hall of Fame in 1972, into the National Cowboys of Color Museum and Hall of Fame in 1983, and the American Indian Athletes Hall of Fame in 1994.

Jackson Sundown, a nephew of Chief Joseph, was with him on the flight of the Nez Perce in 1877. He was the first native American to win a World Championship Bronc Rider title in 1916, at the age of 53, more than twice the age of the other competitors who made it to the final round. He is also the oldest person to ever win a rodeo world championship title. He was posthumously inducted into the Pendleton Round-Up Hall of Fame in 1972, into the National Cowboys of Color Museum and Hall of Fame in 1983, and the American Indian Athletes Hall of Fame in 1994.

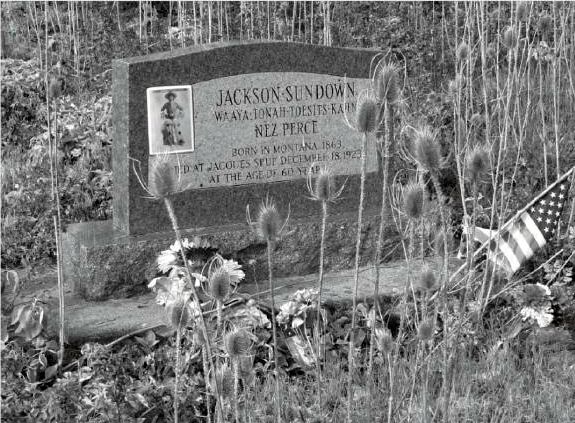

Jackson Sundown (Born 1863-Died December 18, 1923)

a.k.a. George Jackson and Buffalo Sundown,

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn (meaning “Earth Left by the Setting Sun”), also spelled We-ah-te-nato-ots-ha (meaning “Blanket of the Sun”)

Tribal Affiliation: Nez Perce

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn (Jackson Sundown) from an early age worked with and cared for horses. At the age of 14, he was appointed, along with Sam Tilden (Suhm-Keen), to care for and watch over the horses at night on the Nez Perce flight which is called the Nez Perce War of 1877. At the Battle of the Big Hole, he was sleeping in his mother’s tipi when the battle broke out and when soldiers began gathering up prisioners, he hid under a buffalo robe. He was severely burned when a soldier set the tipi on fire.

When Joseph surrendered to General Miles in the Bear Paws of Montana, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn escaped with rifle wounds and made his way to Sitting Bull’s Sioux camp in Canada with White Bird’s group. It is said he escaped by hanging off the side of his horse, making it appear the horse was unmounted.

When he reached Canada, he was given asylum by Sitting Bull and the other Sioux warriors who defeated Custer in 1876. No one seems to know for sure, but it is reported by most historians that he stayed in Canada for two years and was considered a war criminal by the US.

After two or three years in Canada, he crossed back into the United States and made his way to the Flathead Reservation in Montana.

After two or three years in Canada, he crossed back into the United States and made his way to the Flathead Reservation in Montana.

Olive C. Wehr in “To Live On A Reservation ,” writes: “After two years, he stealthily rode to Nespelem, Wash., where Joseph and his surviving followers were confined to a small reservation away from their beloved hills of Wallowa. Joseph warned him not to go there, so Sundown went instead to the Flathead Reservation.”

This story can’t be right, because after Chief Joseph surrendered in 1877 he was first sent to prison at Fort Leavensworth, Kansas for eight months, and then exiled to Indian Territory in Oklahoma for a number of years. Chief Joseph wasn’t moved to Nespelem, Washington on the Colville Reservation until 1885. So either this part of his story isn’t true or the dates are mixed up.

Anyway, when he got to the Flathead Reservation, a Salish woman named Pewlosap (Annie to the whites) took him into her lodge and they lived together without a formal marriage. He had two daughters with his common law wife, Adaline and Josephine.

Adaline Redsky Sundown was born May 26, 1896 near Ronan, in what was then Missoula County and died in August of 1977 at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Polson, MT. She had been married four times to: Louie Hammer, Michel Parker (they had a son Joseph Larry “Itsteenicnukt” Parker, who could speak Salish; Nez Perce, German, Spanish, Russian, and Kootenai.), Pierre Isadore “Peter” Woodcock and finally Pierre Adams (they had a son Patrick Adams, who was a hoop dancer on the Bicentennial Train trip to Washington, D.C.).

Adaline Redsky Sundown was born May 26, 1896 near Ronan, in what was then Missoula County and died in August of 1977 at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Polson, MT. She had been married four times to: Louie Hammer, Michel Parker (they had a son Joseph Larry “Itsteenicnukt” Parker, who could speak Salish; Nez Perce, German, Spanish, Russian, and Kootenai.), Pierre Isadore “Peter” Woodcock and finally Pierre Adams (they had a son Patrick Adams, who was a hoop dancer on the Bicentennial Train trip to Washington, D.C.).

A note in a journal kept by the St. Ignatius Mission House dated Jan. 6, 1909 noted, “Some Nez Perces who are living like beasts have been ordered out of the Reservation, or to get married.”

On February 12, 1909, their records also recorded that a Flathead Indian named Baptist Kakaeshin or Baptiste Ka Kaeshin or Kakashe made an unauthorized trip to Washington to make known some crooked dealings occurring on the Flathead Reservation he did not agree with. He wanted to take Jackson with him as an interpreter. The Agent forbade this, “because he is a stranger and living in adultery.”

On February 12, 1909, their records also recorded that a Flathead Indian named Baptist Kakaeshin or Baptiste Ka Kaeshin or Kakashe made an unauthorized trip to Washington to make known some crooked dealings occurring on the Flathead Reservation he did not agree with. He wanted to take Jackson with him as an interpreter. The Agent forbade this, “because he is a stranger and living in adultery.”

Kakaeshin then agreed to have Joe Pierre interpret but when they got to Missoula, Pierre returned to the reservation and Sundown went with Kakaeshin, deliberately disobeying the Agent’s orders.

Their complaints were that the land north of the Flathead Reservation was not ceded to the U.S. government; the tribe had not consented to the allotment and opening of the reservation; [and that]William Q. Ranft was charging to get people enrolled; that Joe Dixon has forged the consent of tribal leaders on a petition to open the reservation to settlement.

Their complaints were that the land north of the Flathead Reservation was not ceded to the U.S. government; the tribe had not consented to the allotment and opening of the reservation; [and that]William Q. Ranft was charging to get people enrolled; that Joe Dixon has forged the consent of tribal leaders on a petition to open the reservation to settlement.

The BIA Agent’s report on the matters brought up states, “The treaty provides to cession of all land claims except reservation; …that the matter of making allotments and providing for the future support of the Indians has been frequently investigated by officials of the Department, and that it was thought to be best for the welfare of the Indians. BIA has no information on charges for enrollment, and will continue to protect the Indians.”

In regard to the Dixon Allotment Law, he says, “The law was not passed on the petition of the Indians. Congress had the power to make the law and did not ask the consent of the Indians. [The trip to Washington,] D.C. was not needed and normally the BIA does not recognize unauthorized delegations but …I have made an exception in your case out of respect to the advanced age of Baptiste, who has traveled this long distance at much discomfort to himself, no doubt.”

In regard to the Dixon Allotment Law, he says, “The law was not passed on the petition of the Indians. Congress had the power to make the law and did not ask the consent of the Indians. [The trip to Washington,] D.C. was not needed and normally the BIA does not recognize unauthorized delegations but …I have made an exception in your case out of respect to the advanced age of Baptiste, who has traveled this long distance at much discomfort to himself, no doubt.”

Shortly after that, according to the the St. Ignatius Mission House records, the new Indian Agent Fred Morgan announced to Father Taelman that Baptist KaKaeshe is no longer a judge, in punishment for having gone to Washington against the will of the former Agent, and he asks for a recommendation for his replacement. No mention is made about any punishment for Jackson Sundown.

In 1910, Sundown rejoined his tribe on the Nez Perce Indian Reservation in Lapwai, Idaho, where he took an allotment of land and built a cabin. He later married Cecelia Wapshela in 1912, and they built a home at Jacques Spur, Idaho.

In 1910, Sundown rejoined his tribe on the Nez Perce Indian Reservation in Lapwai, Idaho, where he took an allotment of land and built a cabin. He later married Cecelia Wapshela in 1912, and they built a home at Jacques Spur, Idaho.

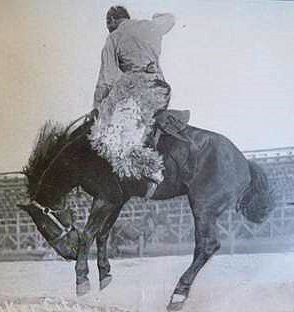

That first summer at Lapwai, when he was 47, at the age most rodeo cowboys are retiring from the circuit, Jackson took his first competition ride. At a rodeo in Culdesac, Idaho, on a dare he rode a notorious bronc, did a standing dismount and them calmly dusted off his blue serge suit. The croud went wild.

That’s where he got the idea to enter rodeo competitions as a way of earning some extra money.

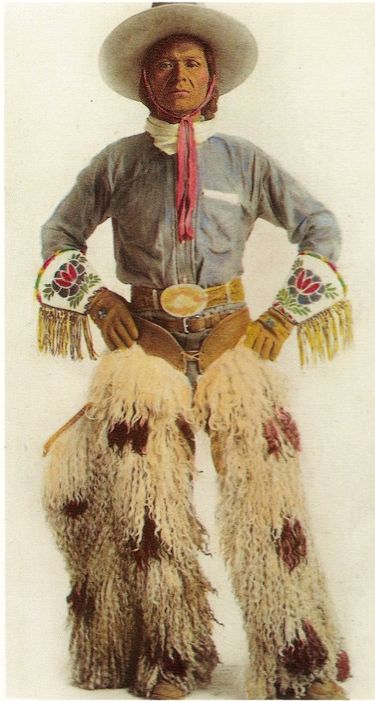

The six foot tall, lean and handsome cowboy didn’t look much like the other cowboys of his era. Aside from the fact that there weren’t many “men of color” competing in rodeos in that era, he didn’t dress like the other cowboys. He wore his long hair in the traditional Nez Perce pompadour, with braids that were tied together and held under his chin with a colorful bandana. He was partial to brightly colored shirts, wore huge angora wool chaps with spots on them, and his favorite shirt was also covered in spots. His gloves were colorfully beaded with a flower pattern. Instead of the usual western cowboy hat, he wore a high, wide brimmed “Indian Hat.” He was quickly a favorite of the rodeo fans.

He wore his long hair in the traditional Nez Perce pompadour, with braids that were tied together and held under his chin with a colorful bandana. He was partial to brightly colored shirts, wore huge angora wool chaps with spots on them, and his favorite shirt was also covered in spots. His gloves were colorfully beaded with a flower pattern. Instead of the usual western cowboy hat, he wore a high, wide brimmed “Indian Hat.” He was quickly a favorite of the rodeo fans.

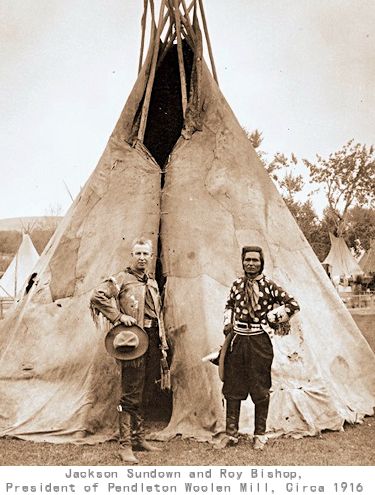

Roy Bishop, the president of the world famous Pendleton Woolen Mills, was so impressed with some of his clothing that he wove some of the patterns into his famous Pendleton blankets. The two men became lifelong friends.

Jackson won many all-around cash pots, which takes the highest average scores from all events, and was also a pretty good bull rider, though he was best known for bareback and saddle bronc horse riding.

By the next year, he had earned enough points to qualify for the Saddle Bronc Finals for the 1911 World Championship at the Pendleton Round-Up, which ended in controversy and protest.

He competed with George Fletcher, an African American, and John Spain, a European American.”

The Moscow Pullman Daily News reported that Sundown took third after falling from his horse which had slammed into one of the judges’ horses, but was not given a re-ride, which is usually given when there is interference with the ride.

Fletcher, who “thrilled the crowd with his first ride,” was ordered a re-ride by the judges, which “was as wild as the first,” and would be awarded second place.

Fletcher, who “thrilled the crowd with his first ride,” was ordered a re-ride by the judges, which “was as wild as the first,” and would be awarded second place.

Spain would be awarded the grand prize amid protests from the crowd claiming he had touched the horse with his free hand, which is an automatic disqualification in bronc riding events.

The town Sheriff Till Taylor is said to have taken Fletchers hat, torn it up and sold the pieces to the thousands of protestors. They handed Fletcher the proceeds and declared him “The Peoples Champion.”

Award-winning Western novelist Rick Steber chronicled the story in his book titled “Red White Black,” that forever changed the sport of rodeo, and the way the emerging West was to look at itself.

Ken Kesey, author of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” also wrote a book titled “Last Go Round,” that tells the story of the hustle and bustle around the 2nd annual Pendleton Round-Up rodeo in 1911.

In 1912 it is recorded that Jackson Sundown (at the age of 49) entered rodeo events in Canada and Idaho (Culdesac, Orofino, Kamiah and Grangeville). He continued to be a favorite with the crowds and more often than not, he was “in the money.”

In 1912 it is recorded that Jackson Sundown (at the age of 49) entered rodeo events in Canada and Idaho (Culdesac, Orofino, Kamiah and Grangeville). He continued to be a favorite with the crowds and more often than not, he was “in the money.”

By 1914 Sundown was having so much success as an all-around rodeo rider that other contestants pulled out of rodeos when they found out he was riding because they knew he would beat them. As a result the rodeo managers decided to hire Sundown to exhibition ride for $50.00 a day to entertain the crowds. He accepted this offer, which kept him in guaranteed money which was still a lot at the turn of the century, but cut him out of the chance to win the really big pots such as those at the Calgary Stampede, Pendleton, and other big rodeos.

In 1914 his regal bearing and presence attracted America’s most famous sculptor of that era, Alexander Phimster Proctor, who hired him to pose for many statues including one for Stanford University, the RCA Building in New York, as well as the heroic piece that now stands in front of the Colorado Capital building.

In 1915 at age 52, he again qualified for the World Championship competiton at the Pendleton Roundup. He placed third again that year, and decided to retire from rodeo, which had wrecked his body. Most rodeo cowboys had already retired by age 40, younger than he was when he first started competing. A discouraged Jackson said he was through with competitive riding where he felt he was not judged fairly, but Proctor talked him into “one more” and paid his entry fees for the 1916 Pendleton Roundup. His rides there are still called the most exciting and unbelievable in rodeo history.

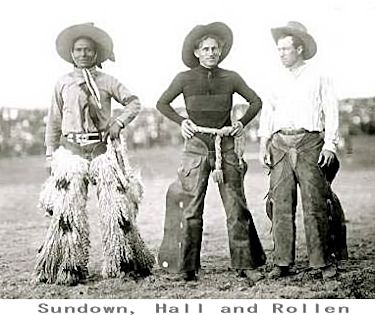

Pitted against him in the finals were two great bronc riders of the day, Rufus Rollen of Oklahoma and Bob Hall of Pocatello. Both men made epic rides, but the ride of Sundown eclipsed them both.

Pitted against him in the finals were two great bronc riders of the day, Rufus Rollen of Oklahoma and Bob Hall of Pocatello. Both men made epic rides, but the ride of Sundown eclipsed them both.

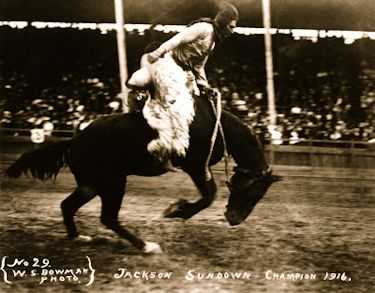

Sundown was twice the age of the other semi-finalists, but advanced after high scores in the saddle bronc and bareback horse riding competitions. His final ride is an event of great mythology to this day among American Indians and rodeo aficionados.

It is told that Sundown drew a very fierce horse named Angel that he had rode before. Angel twisted in circles before exploding into the air several times.

From the moment they left the gate, he spurred the horse from neck to flank continuously. Not for a moment did the punishment abate. They say the horse bucked so furiously that Sundown removed his hat and fanned the horse to get it to cool off, at which time he and the horse merged into one being.

A noisy crowd watched as the only full-blooded Indian ever to compete in the Pendleton Round-up Championship rode to victory. The very ground of the arena seemed to rock with the earth shaking leaps of the outlaw bronc. Sundown rode gloriously into the championship amid an ovation never before equaled. The throngs – White and Indians – cheered themselves hoarse. Sundown won the all-around event and became immortalized as both a cowboy and Indian hero.

When the 1916 World Champion Bronc Rider was awarded his handsome leather tool prize saddle and asked what he would like engraved on the silver plate, he replied Cecelia Wapshela, his wife’s name.

In 1923, Jackson Sundown died of pneumonia. He was buried at Slickpoo Mission Cemetery near Jacques Spur, Idaho. Sundown wasn’t even an American citizen when he died. Congress voted in 1924 to make American Indians citizens of the United States.

A stone monument placed on the grave of the Nez Perce warrior and legendary horseman reads: Jackson Sundown, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, Nez Perce, Born in Montana 1863, Died at Jacques Spur, December 18, 1923 at the age of 60 years, and has a picture of him in his wooly chaps.