| Henry Standing Bear (Mato Najen), Lakota Sioux Intancan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dakota, Lakota, Nakota "Allies or Friends" |

|

|

| |

Henry Standing Bear (Mato Najen), Lakota Sioux Intancan |

Artifact Replicas|Jewelry|Clothing|Figurines|On Sale|New ProductsHenry Standing Bear (Mato Najen), Lakota Sioux IntancanAUTHOR: John Swanson Intancan is the Lakota word for leader. Mato Najen, also known as Chief Henry Standing Bear, was one of the latter day Intancans of the Lakota people. His life spanned the Battle of the Little Big Horn, the Wounded Knee Massacre, and the Indian Reorganization Act. He stood as a proud and progressive leader as his culture was forcibly transformed. It was his leadership which ensured that the Lakota people, and all Native people, would be forever honored by the largest mountain carving on earth. “My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know that the red man had great heroes too.” (1)Those words, written by Chief Henry Standing Bear, rang true to sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski. More than sixty years of work in removing more than eight million tons of stone have helped the red man’s hero emerge from Thunderhead Mountain in the Black Hills of South Dakota. The Crazy Horse Memorial, originally conceived by Chief Henry Standing Bear, now hosts over one million visitors a year. Who was Chief Henry Standing Bear and how did he come to be the Intancan who initiated Crazy Horse Memorial?Henry Standing Bear was born along the Missouri River near Pierre, South Dakota. The year of his birth was probably 1874, although there is no known record of it. Henry used to say that he was born “when the corn was growing green and the rivers were starting to run”.(2) He was Brule Lakota, the son of Chief George Standing Bear and his second wife, Roaming Nation. Roaming Nation’s mother was a sister to Worm, Crazy Horse’s father. Consequently, Henry was a maternal cousin to Crazy Horse.(3) Henry Standing Bear’s genealogy is complex.His father had three wives. Of Henry’s own five marriages, three ended in divorce and two of his wives died. He fathered six children during those five marriages and he outlived all but one. A partial compilation of Henry’s family tree, including the connection to Crazy Horse, is shown below. (4) Worm (Father of Crazy Horse) Rattling Stone Woman (also known as One Horse, was a sister of Worm) George Standing Bear -- Roaming Nation -------- (Daughter of Rattling Stone Woman and 2nd wife of George Standing Bear) Children:At age 14, Henry was one of the youngest and first of the Indian children to attend Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.(5) It was at Carlisle that Henry truly began his education in the ways of the white world. The skills he learned to succeed in the white world would be instrumental in his life’s work to help his people adjust to, and accept, the white man, despite his imperialistic ways. Carlisle contributed to Henry’s attitude and belief system about Indian and white relations.Even during childhood, Henry was eager to learn the white man’s ways. Choosing an english nameWhen Mato Najen went to school, he was elated at the prospect of having a new name, like the white boys. The teacher gave him a pointer, and whirled a big wheel filled with many names for boys. He pointed as he was told, as the wheel slowed to a stop, and found he was indicating “Henry”, and so he was called from then on. For a long time he even supposed there was something mystic about this rite, and so, a sort of divinity in the name.(6) Communication skills are integral to leadership and Henry developed them well at Carlisle. According to the Indian Helper, the newsletter of the Carlisle Indian School, Henry excelled in declam and debate. In one instance, Henry led the debate about the question of whether or not the breaking up of Indian reservations, and the giving to the Indians individual holdings of land, constituted the most important step in their regress toward civilization and citizenship.(7) The content of his argument is not known but, according to Bob Lee, Henry felt strongly throughout his life about the concept of land ownership. He was appalled by the policies which prohibited him from selling his vast acreage of land to further support his work for the social progress of his people.(8) Henry was persistent about things he cared about and his education was no exception. In writing to Captain Pratt, founder and director of Carlisle, after his graduation, Henry stated, “If you had seen our agency when you came you would have said, “How could my boys and girls return and stay home? I found all my horses in a starving state and all my cattle totally gone. They were taken to the badlands during the trouble and were killed by the hostiles. Those were the cattle for which I would have money to put myself though school or college. I am at present an assistant teacher, but will leave soon. I can’t live here any longer. I am very anxious to get more education and will fight for it.”(9) Henry’s way was to fight with his pen. He wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to request the financing his family could not provide. The Commissioner reportably denied Henry’s request on the grounds that, if funds were used to support Henry’s higher education, all Indian boys would expect the same. It was the epitome of a left handed complement if, indeed, it was even sincere.(10) Henry eventually found a way to attend night school in Chicago and also worked there for the Sears Roebuck Company.(11) Although he taught school and lived most of his adult life on the reservation, he spent considerable time working and living in the white world. Henry Standing Bear made many trips to Washington D.C., serving as an interpreter to advocate for, and protect the rights of, his people. He worked for a time for a theatrical company on the east coast. He even spent a year working with his half brother Luther in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows. Henry Standing Bear handled Indian Affairs for Senator Francis Case when Case was a representative. At the time of his death, Henry was an active member of the South Dakota Indian Affairs Commission. (12) Henry knew his way around the white culture and used that knowledge to promote his ideas and dreams. By 1927, Henry found one of his feet in the traditional Lakota world and the other in the established culture of white America. He knew the “old ways” would most likely never return. His acceptance of white leaders was exemplified in a speech he made while adorning President Calvin Coolidge with a traditional Lakota headdress and giving him the Indian name “Leading Eagle”. He stated, “We have nothing to give but our national respect. Our fathers and chiefs, Sitting Bull, Spotted Tail, and Red Cloud, may have made their mistakes, but their hearts were brave and strong; their purposes honest and noble. They have gone to their Happy Hunting Ground, and, we call on you, as our new High Chief, to take up their leadership.” (13) The Crazy Horse Memorial was his dreamThe carving of Crazy Horse Memorial began in 1947 when, after nearly ten years of persistent persuasion from Chief Henry Standing Bear, Korzcak Ziolkowski agreed to come to South Dakota to carve the monument. But in the summer of 1935, Henry was understandably frustrated about the Crazy Horse project when he wrote in a letter to James H. Cook, long time friend of Red Cloud, “I am struggling hopelessly with this because I am without funds, no employment, and no assistance from any Indian or White.”(14) His frustration had been at least five years in the making by then and Henry was down, but not out. Two years earlier, during the summer of 1933, Henry learned of a monument to Crazy Horse to be constructed at Fort Robinson. In letters to James H. Cook, Standing Bear offered his support and willingness to be a part of the project in Nebraska. He also informed Cook that he and others had formed the Crazy Horse Memorial Association to promote the carving of Crazy Horse’s head someplace in the Black Hills. He expressed his concern that the two projects must work for the benefit of each, and not compete with each other.(15) Henry believed it should be the relatives of Crazy Horse who should put up a memorialto him. In the Lakota culture, it would be considered especially appropriate for relatives of Crazy Horse to be the ones who should initiate his memorial.(16) Did Henry get his idea of a Crazy Horse monument from Mt. Rushmore?It’s a good bet he did. Dennis Compos, Henry Standing Bear’s grandson said, “It was his dream. After they put Mount Rushmore there in the Black Hills, the Black Hills being our sacred land, my grandfather got the idea.”(17) His half bother Luther was to have first surfaced the idea in one of his books, all of which were written at the time of the Rushmore carving. Henry even lobbied Gutzon Borglum to have Crazy Horse carved on Mt. Rushmore itself.(18) It is obvious that Borglum turned him down. Undaunted by Borglum’s rejection, Standing Bear continued his quest to get a monument carved, regardless of the sculptor. When writing to Ziolkowski in 1939 to request his sculpting services, he said, “We do not believe that Borglum is the only living man that can do that kind of work”.(19) Ziolkowski was intrigued by Standing Bear’s request. So much so that he spent three weeks with Henry on Pine Ridge in the spring of 1940 discussing the matter and learning about Crazy Horse and the traditional Indian way of life. Naturally, the idea of land ownership was part of the discussions. According to Korczak, “Standing Bear grew very angry when he spoke of the broken treaty of 1868. That was the one I’d read about in which the President promised the Black Hills would belong to the Indians forever. I remember how his old eyes flashed out of that dark mahogany face, then he would shake his head and fall silent for a long while.” (20) While Henry’s anger about the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 seemed to linger, it also appears he had come to accept that the Black Hills were no longer Indian country. In his letter to James Cook in 1935, Henry adds a qualifying adjective to the Lakota ownership of Paha Sapa. He wrote, “Perhaps I have told you that I had originated an idea that an image of the head of Crazy Horse be carved on a rock in the Black Hills as a memorial to the early ownership of the Black Hills by the Sioux Nation and a memorial to Crazy Horse who fought for that country.” (21) Henry knew he must be pragmatic if his dream were to materialize. There was a great deal of mutual respect between Henry Standing Bear and Korczak Ziolkowski and together they agreed on a plan for the monument. Henry’s quiet dignity and pride was never as evident as the day he witnessed the inaugural blast on the mountain in 1948. Henry died in 1953 and was buried in the Episcopal Cemetery at Pine Ridge. His only living descendent was his daughter, Bessie Trumbull. She and others close to Henry pursued the idea of removing his remains from Pine Ridge and reburying him at Crazy Horse Memorial.(24)Korczak’s response to this idea was positive, although he was cautious about verifying the family connection to the request. (25) As he had learned from Henry, the request to honor someone in the Native culture must come from his family. After all, one of the main reasons Chief Standing Bear was the Intancan for the cause of memorializing Crazy Horse was that Henry was his maternal cousin. As Korczak put it, “Standing Bear explained that the Indian has a concept of honoring their great heroes that’s totally different from the white man’s. It was difficult for me to understand at first." "It seems with the Indians, only a relative of a great man has the right to honor that man or build a memorial to him. Other people who are not relatives have no right to honor that great man because somehow those people might have evil motives, want to get something out of it. It is rather beautiful in a way. We white people do the opposite. Relatives do not seek to build a memorial to a great man. We get a group of citizens together, and have them do it. We go through the back door. The Indian uses the direct approach. He says: that man was my ancestor, and he was a great man, so we should honor him – I would not lie or cheat because I am his blood.” (26) Lone Eagle, a life long friend of Henry’s, remembered the conversation in which Henry had expressed his desire to be buried at Crazy Horse Memorial. He recalled, “The Chief was silent for several moments as would indicate his unassuming and retiring nature, and after some time, stated that after the great Spirit should call him to the Happy Hunting Ground, he would never wish for a greater honor that to be laid to rest in the great memorial that had been his dream for many, many years. I told the Chief that if I outlived him that I would do all in my power to have his wish fulfilled. He, in his retiring way, bowed his head and was silent again for several moments – he then reached over and put his hand on my shoulder and smiled and I could see that he was pleased beyond all words.” (27) Although the parties involved in Henry’s reburial all seemed to be in agreement, it remains unclear whether he is or isn’t buried at Crazy Horse Memorial. According to Bob Lee, a member of the Crazy Horse Memorial Association Board, the request to have Henry buried at the mountain may have been the first of its kind, but certainly not the last. Joyce Swan, former publisher of the Rapid City Journal and longtime member of the Crazy Horse Memorial Association Board, wished to be buried at the memorial and his wish was granted. (28) Chief Henry Standing Bear is known as the originator of Crazy Horse Memorial for good reason. He had a strong education and language skills which allowed him to write letters, make speeches, and persuade a sculptor to take on the monumental task. He had a deep affection for his people and for the human race as a whole. His wisdom manifested itself in a common courtesy for all men, regardless of race. He was unassuming and kind and honest. Charlatans were his arch enemy. He was sincere in his approach to honor Crazy Horse and his family lineage gave him the right to do so. As Bob Lee put it, “A lot of white men could have learned much about dignity, integrity, and nobility from Henry Standing Bear”. (29) In corresponding with Henry during the summer of 1934, James H. Cook wrote, “At present, the people at Pine Ridge do not appear to have a great leader among their own race. In time, they will – I predict”. (30) Cook’s prediction may have been prophetic as Chief Henry Standing Bear was a most notable Intancan among his own race for most of the twenty years that followed. Many of the people who visit Crazy Horse Memorial may never know much about Henry Standing Bear. It would not, however, exist without his leadership, his integrity, and his persistence. He had honored and challenged his people with a quiet dignity which remains unshaken by the daily blasts which carve his dream in stone. End Notes: 1. Robb DeWall, Crazy Horse and Korczak (Korczak’s Heritage, 1982), 50. 2. A. R. Ziolkowski to Geraldine Zapata, August 7, 1997. 3. Richard G. Hardorff, The Death of Crazy Horse (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 113. 4. Will G. Robinson to Korczak Ziolkowski, June 26, 1956. 5. Bob Lee, “Ridin’ the Range”, Rapid City Journal, October 25, 1953. 6. A. R. Ziolkowski to Geraldine Zapata, August 7, 1997. 7. Barbara Landis, “References to Standing Bear family in Carlisle Indian School newspapers.” (2005). http://home.epix.net/landis/standingbear.html. 8. Bob Lee, “Ridin’ the Range”, Rapid City Journal, October 25, 1953. 9. Barbara Landis, “References to Standing Bear family in Carlisle Indian School newspapers.” (2005). http://home.epix.net/landis/standingbear.html. 10. Luther Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1933), 240. 11. “Henry Standing Bear Obituary”, Custer County Chronicle, October 22, 1953. 12. Ibid. 13. John Taliaferro, Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Questto Create Mount Rushmore (New York: Public Affairs, 2002), 223. 14. Henry Standing Bear to James H. Cook, September 19, 1935. 15. Henry Standing Bear to James H. Cook, August 4, 1933. 16. A. R. Ziolkowski to Geraldine Zapata, August 7, 1997. 17. Casey Logan, “Local man’s grandfather inspired monument”, Northwest Florida Daily News, May 22, 1998. 18. John Taliaferro, Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to Create Mount Rushmore (New York: Public Affairs, 2002), 328. 19. Henry Standing Bear to Korczak Ziolkowski, November 7, 1939. 20. Robb DeWall, Crazy Horse and Korczak (Korczak’s Heritage, 1982), 55. 21. Henry Standing Bear to James H. Cook, September 19, 1935. 22. Henry Standing Bear to Korczak Ziolkowski, November 7, 1939. 23. A. R. Ziolkowski to Geraldine Zapata, August 7, 1997. 24. State of South Dakota. Custer County. Bessie Trumbull’s Affidavit of Consent to Remove and Re-bury the Remains of Chief Henry Standing Bear, August 23, 1955. 25. Korczak Ziolkowski to Bessie Trumbull, April 22, 1956. 26. Robb DeWall, Crazy Horse and Korczak (Korczak’s Heritage, 1982), pg53. 27. Lone Eagle to Korczak Ziolkowski, February 20, 1956. 28. Bob Lee, interviewed by author, July 23, 2005. 29. Bob Lee, “Ridin’ the Range”, Rapid City Journal, October 25, 1953. 30. James H. Cook to Henry Standing Bear, August 29, 1934. Bibliography Cook, James H. Letter to Henry Standing Bear, 29 August 1934. Custer County Chronicle, 22 October 1953. DeWall, Robb. Crazy Horse and Korczak: The story of an epic mountain carving. Korczak's Heritage, 1982. Hardorff, Richard G. The Death of Crazy Horse: A Tragic Episode in Lakota History. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1998. Landis, Barbara. References to Standing Bear family in Carlisle Indian School newspapers.2005. http://home.epix.net/landis/standingbear.html. Lee, Bob. Interviewed by author, 23 July 2005. Lone Eagle. Letter to Korczak Ziolkowski, 20 February 1956. Northwest Florida Daily News, 22 May 1998. Rapid City Journal, 25 October 1953. Robinson, Will G. Letter to Korczak Ziolkowski, 26 June 1956 Standing Bear, Henry. Letter to Korczak Ziolkowski, 7 November 1939. Standing Bear, Henry. Letter to James Cook, 4 August 1933. Standing Bear, Henry. Letter to James Cook, 19 September 1935. Standing Bear, Luther. Land of the Spotted Eagle. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1933. State of South Dakota. County of Custer. Bessie Trumbull’s Affidavit of Consent to Remove and Re-bury the Remains of Chief Henry Standing Bear. 23 August 1955. Taliaferro, John. Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to Create Mount Rushmore. New York: Public Affairs, 2002. Ziolkowski, A. R. Letter to Geraldine Zapata, 7 August 1997. Ziolkowski, Korczak. Letter to Bessie Trumbull, 22 April 1956.

A Fine Sioux War Bonnet, Sewn with Twenty-Nine Eagle Feathers Giclee Print Buy at AllPosters.com Framed Mounted |

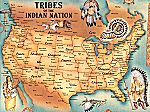

What's New in the Gallery Store: Native American Tribes by States Poster  25 new fringed leather jackets  Zuni Style inlaid stone jewelry More New Products |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||