Kamiakin was an influential chief of the Yakama Tribe, a reluctant signer of the 1855 Walla Walla Treaty creating the Yakama Reservation, and one of the key war leaders during the Northwest’s Indian Wars of 1855-1858.

Early Life

Kamiakin was born around 1800, the first-born son of a Palouse father, T’siyiyak, and a Yakama mother, Com-mus-ni, the daughter of a chief. Kamiakin was familiar at a young age with both his father’s Palouse country along the Snake River and his mother’s Yakama country along the Yakima River. He was immersed in a mix of tribal cultures, including Palouse, Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Spokane, Coeur d’Alene, and Cayuse.

Kamiakin was born around 1800, the first-born son of a Palouse father, T’siyiyak, and a Yakama mother, Com-mus-ni, the daughter of a chief. Kamiakin was familiar at a young age with both his father’s Palouse country along the Snake River and his mother’s Yakama country along the Yakima River. He was immersed in a mix of tribal cultures, including Palouse, Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Spokane, Coeur d’Alene, and Cayuse.

When he was about ten, the family went to live primarily in the Yakama country centered along Ahtanum Creek. (Note: In 1994 the then-named Yakima Tribe changed the spelling of its name back to the original form, the Yakama Tribe.)

Kamiakin helped tend the impressive herds of horses for which his clan was known. The clan’s life revolved around a “seasonal round,” which included wintering in the Kittitas and Ahtanum valleys; spring root gathering on nearby prairies; summer salmon fishing on the Columbia, Wenatchee, Snake, and Spokane rivers; and fall berry-gathering high in the Cascades, according to a definitive biography, Finding Chief Kamiakin: The Life and Legacy of a Northwest Patriot by Richard D. Scheuerman and Michael O. Finley. Because of his father’s Palouse background, young Kamiakin also became familiar with the basalt-ringed lakes of Eastern Washington’s channeled scablands, including Sprague Lake and Rock Lake.

As an adolescent, Kamiakin “acquired his tah, or tutelary spirit,” during a vision quest ordeal high on the slopes of Mt. Rainier. Kamiakin never gave details of this experience — to do so was not allowed — but he later said it was “the severest feat of his life.”

Young Adulthood

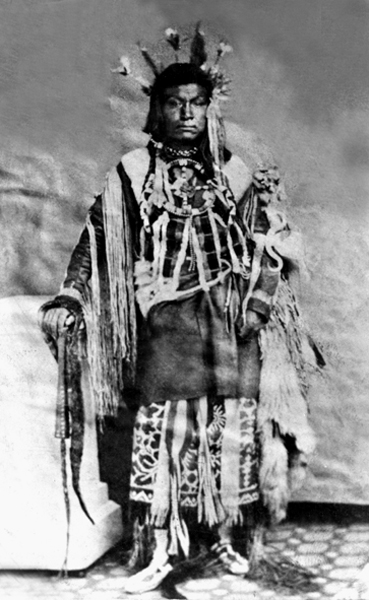

As Kamiakin entered adulthood, he emerged as a natural leader. A number of early fur traders and explorers singled him out for his imposing appearance. The first written mention of Kamiakin came in an 1841 diary kept by an army explorer, Lt. Robert E. Johnson, who was part of Charles Wilkes’ United States Exploring Expedition.

Johnson described Kamiakin as “one of the most handsome and perfectly formed Indians they had met with.” However, Johnson also recorded that Kamiakin refused to sell them any horses and was “gruff and surly.” Fur trader Angus McDonald described Kamiakin as “a fine well-formed and powerful Indian, standing five feet eleven in his moccasins” and “about two hundred pounds, muscular and sinewy.”

At the age of about 25, Kamiakin married Sunk-hay-ee, the daughter of Chief Teias of the Kittitas Valley band. A few years later, he also married Kem-ee-yowah, daughter of the Klickitat Chief Tenax. Kamiakin was the grandson of a chief, the nephew of a chief and the son-in-law of two chiefs — and before long he was considered a chief himself, at least of his band, and an influential person among the other Yakama bands. As early as about 1840, Kamiakin was acknowledged as a key leader of “the greater portion of the Yakamas,” extending up and down the Yakima Valley.

Kamiakin’s Gardens and Irrigation System

Kamiakin and his family established a home camp on a stretch of Ahtanum Creek about 12 miles east of present day Yakima. They still observed the regular “seasonal rounds,” but Kamiakin also obtained some cattle and discovered that cows fattened up as nicely as horses on Yakima Valley grass. He also became known for adopting agriculture early. In fact, Kamiakin deserves credit for a key Yakima Valley agricultural innovation: irrigation.

Kamiakin was growing potatoes, corn, and peas as early as 1845. He and his brothers planted those crops — and later squash and pumpkin — in the fertile bottomlands along the creek. They must have realized what generations of farmers have since learned: Water from the sky was scarce east of the Cascades, but abundant in the glacial-fed streams. So Kamiakin and his band dug an irrigation ditch, a half-mile long, from a spring near the forks of the creek to the garden plots. Early pioneers called it “Kamiakin’s Ditch.”

In at least one winter, those gardens helped feed the missionary priests that had come to live among them (by some accounts, the priests helped construct the canal).

Kamiakin and the Catholic Missionaries

Kamiakin had first invited missionaries into his country in 1847. He had met Marcus and Narcissa Whitman at Walla Walla not long after they arrived in 1836. He had invited some of their fellow Presbyterian missionaries to come to the Yakima Valley. They declined and the ensuing massacre put an end to that idea. So Kamiakin invited two Oblate Catholic missionaries, Eugene Casimir Chirouse and Charles Marie Pandosy, in 1848.

Not all of the Yakamas were in favor of allowing white priests in — many people were “skeptical” and some were downright “fearful.” Yet Kamiakin believed that the missionaries had a “compelling” message and he was convinced a mission would have advantages for his people both spiritual and practical.

The priests built a modest chapel called St. Joseph’s Mission on Simcoe Creek, and by 1852, they moved the mission to Ahtanum Creek, probably to be closer to Kamiakin’s camp. Winthrop described the new St. Joseph’s Mission as a “hut-like structure of adobe clay … plastered on a frame of sticks.” Kamiakin soon grew close to Father Pandosy and often attended morning and evening prayers and went to religious instruction.

In fact, Kamiakin was soon insisting that his people honor the Sabbath. By 1855, about 400 Yakamas were baptized at the little mission, including Kamiakin’s children. Father Pandosy described one of Kamiakin’s children, called by her Christian name of Catherine, as “A playful, joyful happy child, who likes to play tricks beyond all imagination and sensible limits … the true daughter of Kamiakin by her temper, pride, anger and sulking.”

Yet there remained one notable holdout among the baptized: Kamiakin himself. The sticking point was monogamy. The priests insisted on it, but Kamiakin, in keeping with centuries of tribal custom, did not want to give up four of his five wives.

By most accounts, Kamiakin and the priests had a mutual respect for each other. The writings of another priest, Louis-Joseph d’Herbomez, who arrived in 1851, give particular insight into the character of Kamiakin, now in his 50s. After Chirouse “helped himself” to some of Kamiakin’s horses and other supplies without asking, Kamiakin refused for a time to eat meals or even talk to the priests. Yet he didn’t hold a grudge long; d’Herbomez was soon back in good favor with Kamiakin, and rode two hours with him to visit one of Kamiakin’s children, who was ill.

It was a mostly peaceful and friendly time on the Ahtanum, but it was about to change forever.

The First Settlers arrive

In 1853, the first wagon train of settlers came through the Yakima country bound for Naches Pass. Some settlers were not merely passing through; one had even established a claim on traditional Yakama grounds.

Kamiakin rode to Fort Dalles on the Columbia River and asked the commander to remove the settler. The commander complied. It would prove to be one of the few times that Kamiakin would get satisfaction from American authorities.

More white travelers soon came through the Yakima Valley on the way to the Puget Sound country. In 1853, a transcontinental railroad survey team led by Captain George McClellan (later to become famous as a Civil War general), crossed the Cascades and arrived at Kamiakin’s camp on the Ahtanum. McClellan later described Kamiakin as “generous and honest” and “friendly and well-disposed.” George Gibbs, the party’s ethnographer and geologist, said Kamiakin “displayed an honesty not often found.”

Kamiakin closely questioned the party about their intentions. McClellan assured him that they were merely seeking a route through, not into, the Yakima Valley and that Americans had no interest in settling this grassland country. However, this glossed over one of the long-term goals of the railroad survey.

Survey overseer Isaac I. Stevens, soon to become territorial governor, was already convinced that extinguishing Indian title to the lands east of the Cascades was an essential step, not only for the railroad, but also for the future of the territory.

Kamiakin was only partially reassured by the party’s words, and decided to confer with Owhi, his uncle and fellow chief in the Kittitas Valley. Owhi decided to accompany the survey party north to get a better handle on their intentions. Owhi eventually concluded that they could let the Americans have their road, as long as they promised not to stray off it. Kamiakin, for his part, remained wary. He had his doubts about whether the Americans could be trusted.

This survey party spread Kamiakin’s fame throughout the region. Father d’Herbomez wrote shortly afterward: “They took a portrait of Kamiakin to send it to the President of the United States. We have made Kamiakin known as the most powerful chief in the country, being at the same time feared and loved by his subjects. These gentlemen happened to notice it and intended to make him recognized as the big chief of the whole country.”

Yet Father Pandosy, speaking candidly to his friend Kamiakin, warned him that his chiefly powers would prove no match for the encroaching Americans.

“Others will come with each year until your country will be overrun with them,” he told Kamiakin. “Your lands will be seized and your people driven from your homes. It has been so with other tribes; it will be so with you. You may fight and delay for a time this invasion, but you cannot avert it. I have lived many summers with you and baptized a great many or your people into the faith. I have learned to love you. I cannot advise you or help you. I wish I could.”

This disheartening message probably confirmed what Kamiakin already suspected. Kamiakin sought more advice from chief trader Angus McDonald at Fort Colvile. The trader warned Kamiakin that killing one white man was no more effective than killing an ant, because there would be hundreds more to pour up out of the nest; that the whites would eventually overrun the country.

Kamiakin prepares to meet with the white chiefs

Buy Sun Dancer See More Art by Tom Perkinson |

Shortly afterward, a rumor spread among the tribes that Govenor Stevens was going to trek over the Cascades and offer to buy tribal land — but if refused, he would simply seize it. Kamiakin could see only one effective strategy: to unite the region’s tribes. Kamiakin was in a particularly good position to form such an alliance, because of his lifetime connections with the Palouse, Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Spokane, and other tribes spread over what is now Washington and Oregon.

According to early biographer A.J. Splawn, Kamiakin, Kamaikin convened a multi-tribal council on the Grande Ronde River to discuss a unified strategy. They agreed to meet with Stevens and hear what he had to say, but they resolved to refuse to cede or sell any of their lands. They planned to draw up a map of each tribe’s boundaries and then insist that all of these lands be retained as permanent reservations.

When a small governmental envoy led by James Doty and Andrew Jackson Bolon arrived at the St. Joseph’s Mission in 1855, Kamiakin was in no mood to be welcoming. Doty said he wanted to purchase all of their country and give back only a portion for permanent reservations.

At first, Kamiakin was, in the words of Doty, “either silent or sulky.” When Owhi and some other chiefs arrived, Kamiakin finally came into the lodge, ominously bearing arms. During the meeting, he spoke only twice, first to say that if Stevens wanted a treaty council, it should be held in Walla Walla Valley — possibly because Kamiakin wanted the backing of the tribes in that region. Second, he said he did not want any of Doty’s gifts of tobacco and cloth. Doty protested that the gifts were simply “to indicate our friendship.” Kamiakin later said he believed that whites gave such gifts and later claimed that Indian lands were purchased by them.He made a point later of saying he had never accepted from the Americans the value of a grain of salt without paying for it.

The envoys departed after securing a commitment from Kamiakin and the other chiefs to meet Stevens in the Walla Walla Valley in May 1855. Doty came away convinced that Kamiakin was the “head chief” of all of the Yakama bands and could represent them and also the Palouse tribe at the council. Scheuerman and Finley call this a “serious misconception,” since Kamiakin was chief of only one of many Yakama bands and would never claim to speak for all of them. Kamiakin was, after all, only half-Yakama. Even Doty recognized — and attempted to use to his advantage — the fact that there was a “considerable amount of family rivalry existing between Kamiakin and his wife’s people.” Father Pandosy wrote, prior to the Stevens council, that the bulk of the Yakama “were generally well disposed towards the Whites, with the exception of Kam-i-ah-kin.”

Walla Walla Treaty Council

When Stevens convened the Walla Walla Treaty Council in late May 1855 near Mill Creek, more than a thousand Indians were in attendance. Yet Kamiakin’s idea of a united front soon crumbled. The day before the council opened, Kamiakin asked all of the leaders to plan strategy, but most of the Nez Perce refused to come because they wanted to pursue their own strategy. A Nez Perce chief said he also didn’t want the “Cayuse troubles on our hands.”

As the treaty council dragged on for days, Kamiakin remained mostly silent, probably reflecting both his skepticism about the council and also his desire not to put himself above his uncle Owhi and the other Yakama chiefs. Stevens couldn’t quite figure Kamiakin out.

“He is a peculiar man, reminding me of the panther and the grizzly bear,” wrote Stevens. “His countenance has an extraordinary play, one moment in frowns, the next in smiles, flashing with light and black as Erebus the same instant.” Kamiakin simply did not trust the government to keep promises forever, or even into the next generation. And he knew the stakes couldn’t be higher.

“With more far-reaching wisdom than the rest, he probably saw that this surrender of their lands and intrusion of the white men, would be the final step in destroying the nation,” said Lt. Lawrence Kip, who fought against Kamiakin in later battles.

One observer noted that Kamiakin was the “greatest impediment” to ceding lands and “nothing could move Kamiakin.” At one point, Stevens even offered Kamiakin a $500 annual salary for 20 years. After many tedious days of meetings, Kamiakin’s patience wore thin. On June 9, 1855, Kamiakin arrived at Stevens’ tent and told him he was “tired of talking, tired of waiting,” and was heading home.

Stevens immediately launched into a hard sell. He told Kamiakin that as the leader of his people he couldn’t leave without a decision on a treaty. Accounts differ about what was actually said on this fateful day. Doty, recording the events, said simply that Stevens was persuasive and convinced Kamiakin to sign. Yet Andrew Pambrun, interpreting for Kamiakin, later said that Stevens held up the treaty and said that if Kamiakin and the other chiefs didn’t sign, “you will walk in blood knee deep.”

William C. McKay, a Stevens assistant, said that an exasperated Kamiakin told Stevens that if he so badly wanted his “mark” (signature) on a piece of paper, then the governor could take it, “if it will do you any good; it is no use to me.”

Both Pambrun and McKay later told a dramatic story about Kamiakin’s barely suppressed emotions when he finally walked up and made his X.

“All the chiefs signed, Kamiakin was the last and as he turned to take his seat, the priest (Chirouse) hunched me and whispered, look at Kamiakin, we will all get killed,” wrote Pambrun in his memoirs. “He was in such a rage that he bit his lips until they bled profusely.”

The treaty ceded 17,000 square miles of traditional tribal land in exchange for a 2,000 square-mile reservation — which did not even include Kamiakin’s camp on the north bank of the Ahtanum. Nor did any of the other reservations created in the council include such crucial fishing areas as Celilo Falls and Kettle Falls on the Columbia River.

Pambrun was under no illusion that these treaties meant peace. In fact, he was surprised that war didn’t break out right at the treaty grounds.

“Everything appeared to be tranquil, but only apparently so,” wrote Pambrun. “I expected an immediate outbreak but from one cause or another, did not occur until autumn, but their plans were not then well matured.”

Going to War

Kamiakin returned to his Ahtanum camp and again tried to unite the tribes. He invited leaders in to discuss a plan, and the St. Joseph’s missionaries reported seeing bands of Palouse and Nez Perce heading over to Kamiakin’s camp “to plot, to get ready.”

Meanwhile, gold had been discovered in the Colville country and parties of miners were already crossing the Yakama reservation land in what the Indians considered violation of the treaty (although the treaty would not be ratified by Congress until 1859).

Kamiakin’s words show that he was now resolved to fight. He told his fellow chiefs that if they didn’t stop the white intruders, they were fated to be a “degraded people.” He proposed sending men to the mountain passes to head off miners and other intruders. But if the miners persisted and if soldiers came, “we will fight.”

In August 1855, Owhi’s son Qualchan and a party of warriors attacked and killed six miners in the Yakima Valley after one miner sexually assaulted Owhi’s niece.

Then in September 1855, a band of Yakamas came upon their own contentious Indian agent, Bolon, who was quitting the country and heading back to Fort Dalles. They traveled peacefully together for a time. But at camp that evening, the Indians wrestled Bolon to the ground and cut his throat. The Indian wars were on; they would last until 1858.

Battle of Toppenish Creek

Kamiakin was not present at either incident, yet the frontier press spread stories calling Kamiakin the prime instigator. On October 1, 1855, Major Granville O. Haller marched toward the Yakima Valley from Fort Dalles with two companies of troops. Kamiakin heard the news two days later and sent for Owhi and Qualchan and their bands of fighters.

About 300 Indians under Kamiakin and other leaders rode south and encountered Haller’s men not far from Toppenish Creek. Fierce fighting ensued, but the Battle of Toppenish Creek remained in the balance until 200 men under Qualchan arrived and drove back the outnumbered soldiers. Five soldiers died along with an unknown, but probably fewer, number of Indians.

Haller retreated that night back to The Dalles. Kamiakin, now about 55, took part in the attack. Splawn wrote that Kamiakin’s “stentorian voice could be heard above the noise of battle, urging his braves to stand.”

Kamiakin saw the Battle of Toppenish Creek as evidence that he was pursuing the right course.

“If we had not fought,” Kamiakin said to Owhi, “they would have kept coming, but we have driven them away.”

Yet Kamiakin had neither the time nor the inclination to celebrate a victory. Within weeks, a new force of nearly 500 soldiers — mostly Oregon Volunteers — assembled at Fort Dalles and marched north to put down the Yakamas. Kamiakin found himself criticized from all sides. The whites blamed him for inciting Indians to violence and leading a belligerent Indian confederation. His own tribe, under great stress, divided into factions, with some blaming Kamiakin for leading them into an unwinnable war, and others blaming him for signing the treaty.

It was in this fraught atmosphere that Kamiakin sat down with Father Pandosy and dictated an open letter to the oncoming soldiers and to America in general. On November 11, 1855, the soldiers found the letter on Pandosy’s table — right before they burned the mission to the ground and plundered Kamiakin’s irrigated gardens. Both Kamiakin and Pandosy had already fled north.

In this remarkable letter, Kamiakin makes a heartfelt plea for peace — “we are quiet, friend of America” — but also gives vent to his boiling frustrations. He said the governor has “thrown us out of our native country among a strange land among a people who is our enemy,” referring to the 14 disparate bands to be jammed together on a Yakama reservation. He said that if Stevens had asked for only “a piece of land” in each tribal homeland, “we would have given willingly what he would have asked us and we would have lived with all others as brothers.” Instead, the Americans wanted them to “die of famine little by little.”

“It is better,” said Kamiakin, “to die at once.” He said that American authorities have “hanged us without knowing if we are right or wrong” but never hanged Americans who killed Indians. As for the slain miners, Kamiakin said they had first shot his people because the Indians “did not want to give them their wives.”

As for Bolon, the Indian agent had insulted his people and threatened to send soldiers to destroy them. Still, said Kamiakin, they had been willing to allow Bolon to leave peacefully — until Bolon “went on talking with too much harshness” and threatened them yet again.

Then Kamiakin makes one last heartbreaking attempt to forestall war.

“If the soldiers and the Americans after having read the letter and taken knowledge of the motives which bring us to fight, want to retire or treat in a friendly [manner], we will consent to put arms down and to grant you a piece of land in every tribe, as long as you do not force us to be exiled from out native country,” said Kamiakin. “Otherwise we are decided to be cut to pieces.”

Then Kamiakin defiantly — and desperately — resolves that the men guarding the camps will kill their own wives and children “rather than see them fall into the hands of Americans to make them their toys.”

When Major Gabriel Rains found and read Kamiakin’s letter, he certainly did not want to “retreat or retire.” His written response was ferocious. He accused Kamiakin of unprovoked murder, said his “foul deeds were seen by the eye of the Great Spirit” and said his people would be cursed to be “fugitives and vagabonds.”

“We will not be quiet, but war forever until not a Yakima breathes in the land he calls his own,” wrote Rains. “The river only will we let retain this name, to show all people that here the Yakimas once lived.”

Resistance from Idaho to Puget Sound expand the Indian Wars

Battles and skirmishes ensued on both sides of the Cascades, although it is unclear whether Kamiakin was involved in any of them. The army and the press believed that Kamiakin was roaming the country stirring up resistance among tribes from Idaho to Puget Sound. Lt. Kip, in his account of the Indian Wars, said Kamiakin “occupied the same position with them that Tecumpsah formerly did” with the Eastern tribes. Some of this was probably true.

At one point, Kamiakin was reported to be camped between the Columbia and Snake Rivers with over 1,000 warriors from the Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Cayuse and Palouse tribes. In April 1856, Kamiakin led 150 warriors in a fight at Satus Creek in which an officer was killed. The rest of the detachment drove “the notorious Chief Kamiakin” northward, but they were “in no condition to hunt him down,” according to the official report.

Colonel George Wright was sent to the Yakima Valley in April 1856 to stamp out the resistance, and to find Kamiakin and get him to parley. In the Naches Valley, he saw large numbers of Indians on the ridges. Through messengers, he asked Kamiakin to come and make peace. Kamiakin met with Owhi and the other chiefs that night and the fracture in the Yakama tribe became clear. Splawn said there was “vast amount of jealousy” about Kamiakin’s accumulation of power. Owhi angrily upbraided Kamiakin for his inability to find an answer to their problems. Owhi said, “I have asked you … and you do not know!”

So Owhi decided to come up with his own answer. He said if Wright would agree to quit fighting, so would he. He and several other chiefs, including Qualchan, rode to Wright’s camp the next day and pledged peace. Yet Wright was still uneasy that Kamiakin and his brothers Skloom and Showaway were not involved in this agreement.

“I sent word to Kamiakin that if he did not come over and join this treaty, I would pursue him with my troops,” wrote Wright. “And no Indian can remain a chief here in this land if he does not make his peace with me.”

The Second Walla Walla Council

Kamiakin left the Yakima Valley — rarely, if ever, to return. In May 1856, he rode northeast to talk to Spokan and Coeur d’Alene leaders. Then in September 1856, Govenor Stevens decided to hold a Second Walla Walla Council and he hoped to lure Kamiakin there. Before the council opened, Kamiakin sent back word of his terms: The return of all the Indian lands ceded in 1855 and the expulsion of all white settlers. These terms were, of course, unacceptable to Stevens.

“It is useless to talk,” Kamiakin said. “Govenor Stevens knows my heart already, everyone knows that I am for war.”

The Second Walla Walla Council opened amidst tensions and rumors that Kamiakin and his Yakama warriors were nearby. The atmosphere was so “unmistakedly hostile” that Stevens decided to move his camp closer to the protection of Lt. Colonel Edward Steptoe and his Army camp on Mill Creek.

While making that move, a remarkable and accidental meeting took place. Pambrun, who was there, described it like this:

“We had proceeded but a short distance when Kamiakin and his warriors came in sight, making a fine show, accoutered in all the Indian war paraphernalia, … When the Indians came within a few hundred yards, the Governor ordered me to go and meet them and learn their intentions.”

Pambrun’s horse stampeded and sent him racing helplessly through the startled Indians, who apparently regarded this as an “act of bravado.” A tense moment ensued, broken by Kamiakin.

“The wily Kamiakin, seeing our attitude, cooled down, and wished to shake hands (with the governor), but I remonstrated, telling the governor, it would not do at all, as the Indians would be mingling with our teamsters and herders and perhaps stampeding our animals. In fact, there was no knowing what the consequences would be from such indiscretion, the Indians numbering at least five to one of our fighting force.”

The governor was talked out of shaking hands and made do with telling Kamiakin that he would be glad to shake hands once they got settled into camp. But the moment was lost and Kamiakin never showed up at the camp. The council ended in futility soon afterwards, and Stevens and his party were attacked by Qualchan and other young warriors as they departed for Olympia. The governor had to return under army escort.

The Steptoe Episode

Kamiakin, his family and his band of mostly Yakama and Palouse warriors, camped mostly at a spot on the Palouse River. He made occasional treks to the Spokane and Coeur d’Alene country and to the Snake River country, but he avoided any place where he might confront whites.

Kamiakin made some conciliatory gestures, including releasing unharmed an army cattle herder captured by some Yakama warriors. The released cattle herder relayed an overture of peace from Kamiakin. Yet this didn’t prevent newspapers west of the Cascades from continuing to portray Kamiakin as the mastermind of the entire uprising.

They even called him “General Kamiakin” for his part in an earlier bloody attack at The Cascades army post on the Columbia, even though there is no evidence Kamiakin was there. Stevens, in a letter to a New York newspaper, also accused Kamiakin of attacking “substantial and quiet citizens” at The Cascades and other places.

An 18-month lull in the Indian Wars encompassed all of 1857 and the first part of 1858. It came to an end in May 1858 when Lt. Colonel Steptoe marched north from Fort Walla Walla with 157 soldiers and two howitzers. It was designed as a show of strength to punish sporadic raids and was seen as deliberate provocation by the Spokanes and Coeur d’Alenes. They paraded in front of Steptoe’s troops on Pine Creek near what is now called Steptoe Butte. In a parley, Steptoe claimed his visit was entirely peaceful.

Kamiakin’s band had been root-digging in the Coeur d’Alene country at the time and he arrived with his warriors that night to participate in a council of chiefs. Kamiakin believed that his coalition of tribes was finally having an effect and that the soldiers would peacefully retreat in the face of such opposition. Yet Kamiakin was upbraided by an angry Palouse chief for “voicing caution at the moment of triumph.”

The next day, May 17, 1858, the Steptoe Battle or the Battle of Tohotonimme commenced when Steptoe moved toward Pine Creek. Fierce fighting continued all day, ending only when the outnumbered Steptoe finally retreated under cover of darkness. Seven of Steptoe’s men died and he had to abandon his howitzers. There were some reports that Kamiakin took part in the battle, but he went unmentioned in the most significant accounts. Yet that didn’t prevent the newspapers on the coast from blaming the “disaster” on the “cunning treachery of Kamiakin.”

Battle of Four Lakes and Battle of Spokane Plains

The result of this Indian victory, however, was an immediate resolve by the army to force “complete submission” of the tribes. Once again, it was Colonel George Wright who was sent to do the job. He marched north from Fort Walla Walla in August 1858 with at least 800 soldiers, many equipped with new, deadly long-range rifles.

Kamiakin and Palouse chief Tilcoax held together a confederation of tribes, perhaps grown overconfident from the Steptoe victory. They confronted Wright’s force at the Battle of Four Lakes between present-day Cheney and Spokane on September 1, 1858. Kamiakin and his Yakama and Palouse warriors commanded the center of the line. Wright’s lethally accurate rifles and cannons cut up and scattered the Indians, some of whom were still fighting with bows and arrows.

Kamiakin and the surviving Indians fled north about six miles, pursued by Wright. There, on September 5, 1858, the decisive Battle of Spokane Plains commenced. Again the soldier’s firepower decimated the Indians. At one point in the day, Kamiakin was seated on his horse, with his wife Colestah by his side, when a howitzer shell exploded in the tree overhead. A falling limb struck Kamiakin and knocked him from his horse, severely injuring him. His wife helped evacuate him to the family camp on the Spokane River.

The victorious Wright soon demanded that Kamiakin, Owhi, and Qualchan, come to his camp and submit to surrender terms. Owhi and Qualchan complied. Kamiakin never showed up, either because of his injuries or his deep suspicion of Wright’s intentions. Qualchan was summarily hanged, and Owhi was later shot trying to escape.

The Indian Wars are over.

Kamaikin and his family, now outcasts, trekked eastward toward the Rockies. The tribes in the Pend Oreille country wanted nothing to do with them. They continued over the Bitterroots into Montana and probably spent some time north of the Canadian border. They stopped at the St. Ignatius Mission in the Flathead country, but were not welcomed there, either. The family slogged far up the Bitterroot Valley to near what is now Darby, Montana, but found a chilly welcome there. The tribes feared whites would take revenge on anybody harboring the notorious Kamiakin. Yet there they remained, mostly shunned.

During the winter of 1859, Father Pierre Jean DeSmet (1801-1873) of the Sacred Heart Mission in Coeur d’Alene country, went on an expedition over the Bitterroots to find Kamiakin. What he found was a desolate and starving camp.

“Kamiakin, the once powerful chieftain, who possessed thousands of horses and a large number of cattle, has lost all, and is now reduced to the most abject poverty,” wrote DeSmet.

DeSmet had been given the go-ahead by authorities to propose a peace plan, in which Kamiakin and the other influential refugee chiefs would be allowed to return to their tribes to ease the transition to the reservations.

After meeting with Kamiakin, who professed a “path of peace,” DeSmet was more convinced than ever that Kamiakin’s return would have a “most salutary effect among the Indian tribes.”

In May 1859, Kamiakin made the trek to Walla Walla to discuss this with government officials. He had to use borrowed horses — his own were in poor condition. Yet while camped outside of Walla Walla, he heard rumors that local whites planned to lynch him. So Kamiakin slipped out of camp and was soon back in the Bitterroots. The family later moved to a spot near Lake Coeur d’Alene.

Last Efforts to Win Kamiakin Over

The government made another attempt in 1860. A Yakama Indian agent found Kamiakin and offered him full amnesty, a farm and a $500 annual income. The agent needed “firm Indian leadership to bring order to the new reservation.” Kamiakin declined on the grounds that he did not recognize the treaty.

Another agent, W. B. Gosnell, made similar overtures after becoming convinced that Kamiakin’s character had been misunderstood. He wrote that although Kamiakin went to war, “his whole course was marked by a nobleness of mind that would have graced the General of a civilized nation.” He said that Kamiakin “never harmed women and children of settlers, or waylaid the lone traveler, but has been in many instances their protector.”

In 1860, he and his family went back to familiar land along the Palouse River, between today’s St. John and Endicott, where they were still able to follow their seasonal rounds of root-digging, berry-gathering and salmon fishing.

Kamiakin lived there in relative peace until about 1865. He planted potatoes and corn and his sons marked out a race course. He became friendly with the Sacred Heart Mission priests and his five youngest children were baptized in 1861. In 1865, he and Colestah had a new son, but Colestah soon became ill and died.

Life at Rock Lake

Kamiakin grieved so deeply that his sons encouraged him to make a new camp at Rock Lake, a deep blue lake in the channeled scablands north of the Palouse River. He and his family established camp on a flat near the Rock Creek outlet. They fished and bathed in the lake, planted big gardens and maintained a herd of cattle.

Yet increasing numbers of white settlers were beginning to arrive in the country and some settled near Rock Lake. In 1870, Kamiakin told an Indian agent that “he and his people had been deceived, lied to and tricked in that treaty by the white men, who were rapidly coming from the East” and taking their country.

In 1872, a Rock Lake rancher and his son stormed into Kamiakin’s camp, damaged their gardens and ordered them to move. Kamiakin appealed to authorities, who upheld Kamiakin’s claim. Local ranchers were ordered to “accept Kamiakin’s presence.”

In 1865, young cowboys Willis Thorp and Andrew J. Splawn rode cold, wet and exhausted through the Palouse country after a cattle drive. They came upon a lone wigwam with an old man, a woman and some children. They asked for help and directions, and the old Indian accompanied them 18 miles to a store in Sprague and chatted amiably with them the entire way. When the cowboys said they were headed to the Yakima Valley, the old man’s eyes “flashed fire.” He had once lived above the mission at Ahtanum, he said. He asked the young men what the country was like now; who they knew.

At the store, the trader called him by name: Kamiakin. Splawn immediately recognized the name and asked if he was the chief of the Yakamas.

“For a moment he was silent; then with proud mien, he stood erect and said: ‘Yes.’ Once, he said, his horses could be counted by the thousands and his cattle grazed many hills. He had fought for his country until his warriors were all dead or had left him,” wrote Splawn.

Then he rode off, head bowed. Splawn, 50 years later, was moved to write a comprehensive biography of the man he met long ago at that store.

Last Years of a Hero

Kamiakin, now in his 70s. realized that his family could not stay at Rock Lake forever. He advised his children to move to the newly established Colville Reservation, under the leadership of an old friend, Chief Moses.

Yet Kamiakin stayed put. Then in July 1876, the old chief became ill. He lost weight and was bedridden for weeks. In April 1877, he took a turn for the worse. One day he woke up and said, “I always have dreamed and seen things and could read people’s minds. Now I know there is a heaven. I can see it.”

The man who had held out against baptism for decades finally asked for priest. A priest came from the Sacred Heart Mission at DeSmet and finally baptized Kamiakin under the Christian name Matthew. The next day, Kamiakin died.

Yet even in death, he was not allowed to sleep peacefully. A year later, a scientist and relic-hunter named Charles H. Sternberg came to Rock Lake, learned about Kamiakin’s gravesite, and, under cover of darkness, dug up Kamiakin’s body and stole his head. Kamiakin’s family discovered the desecration later. They re-buried Kamiakin’s bones in a secret spot on the other side of Rock Lake. Yet his skull was never found.

His reputation, however, grew in death. Splawn wrote his biography of Kamiakin in 1917 and subtitled it “The Last Hero of the Yakimas.”

“From the standpoint of an Indian, he was a hero and patriot,” wrote Splawn, “who did his duty to his people as he saw it.” Splawn calls him the “Tecumseh of the Pacific Coast” and “one of the best of the great American Indians of history.”

Today, three schools are named after him: Kamiakin High School in Kennewick, Chief Kamiakin Elementary in Sunnyside and Kamiakin Junior High in Kirkland. Perhaps even more fittingly, pioneers also gave a variation of his name to a high outcropping in the Palouse country, Kamiak Butte. From its summit, a visitor can look out over miles and miles of the land that Kamiakin struggled for.

Further Reading:

Ka-mi-akin, the last hero of the Yakimas

Indians of the Pacific Northwest: A History (The Civilization of the American Indian Series)

A Little War of Destiny: The Yakima/Walla Walla Indian War of 1855-56