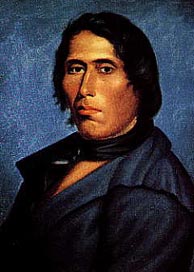

Last Updated: 19 years Tenskwatawa was one of a set of triplets born a few years after Tecumseh. One triplet, Sauwaseekau, was killed at the Battle of Fallen Timbers; the second, Kumskaukau, may have died young, for there are no records of his life; and the third, who would eventually be known as Tenskwatawa, was a fussy baby who was given the name Lalawethika – He Makes a Loud Noise

Later in life, he would be known as the Shawnee Profit.

Unlike Tecumseh, Lalawethika was a clumsy child who was woefully unskilled in hunting and would never become a warrior – a serious social handicap for a young man in Shawnee society. Lalawethika lost his right eye in an early hunting accident and, as he grew older, developed a fondness for whiskey and quickly degenerated into severe alcholism.

Despite his flaws, Lalawethika was devoted to Tecumseh, and the older brother acted as his protector.

Like other great events in the Upper Country, it began with a prophet’s vision. Tenskwatawa was mired in a life of alcohol and despair when, in 1805 he fell into a deep trance. Awakening, he began to preach a compelling message from the Great Spirit.

The ways of the white men, he proclaimed, were an evil that corrupted all they touched. Not only did whites continue to devour Indian lands – another 48 million acres had been ceded through bribery or coercion since the 1795 Treaty of Fort Greenville – but their very presence brought spiritual decay. Dependent on the white world’s tools, enthralled by its trinkets, and poisoned by its whiskey, Indian people were losing their very soul.

Tenskwatawa called for a total rejection of white culture – its clothing and technology, its alchol, and its religion. He also denounced the selling of land. No one really owned the land, he reminded his listeners, since by ancient tradition it belonged to everyone in common as a gift from the Great Spirit.

Along with this bracing message, the Shawnee Prophet echoed another powerful refrain: the vision of an intertribal confederacy that would embrace all Indians everywhere. The person who came closest to making it happen was the Prophet’s brother, Tecumseh.

Tecumseh stood six feet tall and cast a shadow that reached across the nation. A spellbinding orator, regally handsome, wise in council and courageous in battle, he was perhaps the greatest native leader to step forward since the European invasion began in 1492. He led the Shawnee forces during Little Turtle’s War, and he would not accept defeat: his signature is missing from the greenville treaty. He was a man of learning – he studied the Bible and world history — and compassion. More than once he intervened to prevent the torture of prisoners, a common practice among both natives and whites.

More importantly, Tecumseh thought of himself as an Indian first and a Shawnee second. Like his brother, he was inspired by a vision of Indian Unity. The tribes must put aside their age-old feuds, he argued and join together in a great military confederation – a single Indian nation embracing all of eastern North America, from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

The whites are already nearly a match

The whites are already nearly a match

for us all united, and too strong for any one

tribe alone to resist. Unless we support

one another with our collective forces, they

will soon conquer us, and we will be driven

away from our native country and

scattered as leaves before the wind…

~~~Techumseh, Shawnee~~~

In pursuit of that vision, the two brothers set up headquarters in 1805 in an area just outside the now-abandonedFort Greenville. Intended as a place where native people could live free of white influence, it proved a powerful magnet for the Shawnee, Ottawa, Huron, Winnebago, Potawatomi, Ojibwa, and others. The place came to be called Prophet’s Town.

The combination of the two brothers, one a political activist and the other a religious zealot, was powerful, and the size of their following grew. Tecumseh began to visit various tribes throughout the Northwest, filling the ears of all who would listen about the danger the whites posed to their land. Tecumseh was realistic about the Native Americans’ chances of reclaiming land in the East, but he hoped to stop white expansion at the border agreed to in the Greenville Treaty. Despite Harrison’s recent land purchases in Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, Tecumseh pointed out the questionable nature of such transactions and dismissed the United States’ claims.

Tenskwatawa traveled as well, although not as extensively, going to Black Hoof’s village on the Auglaise River and preaching several sermons where he made a number of converts. The Delawares, hearing of Tenskwatawa’s condemnation of rival religious leaders and Indians who followed white ways as witches, invited him to come to their villages on the White River and help them purify themselves.

One old woman accused of witchcraft was roasted over a slow fire for four days, and four others were tortured and put to death. Tenskwatawa moved on to some Wyandot villages on the Sandusky River, where more witches were found, but fortunately for the, their chief forbade their persecution. ( Unlike Tenskwatawa, Tecumseh was always adamently opposed to any use of torture.)

Harrison quickly learned of Tecumseh’s travels to various tribes, but as he had not yet learned the nature of Tecumseh’s visits, he was not unduly alarmed. When he heard of Tenskwatawa’s witch trials, however, he sent a message reprimanding them for listening to what Harrison maintained was a false prophet.

Eager to expose Tenskwatawa as a fraud, Harrison advised the Delawares to demand some sign of divinity from the new prophet, adding, “If he is really a prophet, ask of him to cause the sun to stand still – the moon to alter its course – the rivers to cease to flow – or the dead to rise from their graves.”

Harrison’s strategy backfired when Tenskwatawa accepted the challenge, announcing that he would cause the sun to stand still on June 16, 1806, at Greenville. A large crowd showed up at the appointed place and time and observed a miracle – a dramatic total solar eclipse.

The Americans protested that Tenskwatawa had somehow learned from some whites or an almanac when an eclipse was to take place, but many of the Indians who had been wavering were now convinced that he did have incredible supernatural powers. Pilgrims began to swarm to Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh’s village as stories circulated that the Prophet could heal wounds and diseases and perform many other miraculous feats.

Although most of the visitors came to see Tenskwatawa, Tecumseh was able to further his political agenda, selecting his main lieutenants from among the pilgrims. While Tenskwatawa remained occupied by his religious activities, Tecumseh began to organize the community and to capitalize on the flow of people.

Many pilgrims were converted to both Tenskwatawa’s religion and Tecumseh’s politics and preached both these messages when they returned to their own tribes.

Tecumseh’s success was a cause of concern for the U. S. government, as a main objective of the Americans from the beginning of their struggle with the Indians had been to keep them divided.

In April 1807, a messanger was sent to Tecumseh from a low-ranking federal agent warning him that he and his followers needed to vacate Greenville immediately, as they had settled there in violation of the Fort Greenville Treaty.

Tecumseh informed the messenger that if the president of the United States wanted to negotiate with him, he had better send someone of higher rank. The agent sent numerous messages to Harrison expressing his suspicions of the two brothers, but Harrison did not agree that they were a threat. He had demanded explanations of the brothers’ activities in the past, but both had managed to convince him that they were simply pious, clean-living, politically neutral religious leaders.

Harrison had even complimented Tecumseh in a letter written to the secretary of war, stating that he seemed to be a “bold, active, sensible man daring in the extreme and capable of any undertaking.”