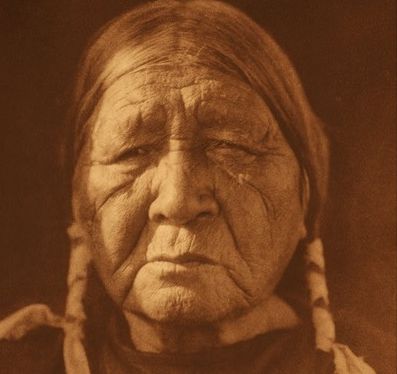

Sanapia, whose Christian name was Mary Poafpybitty, was born in the spring of 1895 in a tepee pitched near Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Her family had travelled to Fort Sill to obtain rations. Because she was unsure of the actual date of her birth, Sanapia later adopted an arbitrary date of May 20, 1895. The sixth of eleven children born to her Comanche father David Poafpybitty and Comanche-Arapaho mother Chappy Poafpybitty, Sanapia grew up with five older brothers, three younger brothers, and two younger sisters.

Sanapia, whose Christian name was Mary Poafpybitty, was born in the spring of 1895 in a tepee pitched near Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Her family had travelled to Fort Sill to obtain rations. Because she was unsure of the actual date of her birth, Sanapia later adopted an arbitrary date of May 20, 1895. The sixth of eleven children born to her Comanche father David Poafpybitty and Comanche-Arapaho mother Chappy Poafpybitty, Sanapia grew up with five older brothers, three younger brothers, and two younger sisters.

Sanapia’s mother refused to accept white culture and would not even speak English in a white man’s presence. Sanapia’s father, however, became a Christian. After he embraced Christianity, he turned his back on his Comanche heritage, and although he never directly attacked the old Comanche beliefs, he ignored or withdrew from them. But Sanapia did not recall any instances of her father interfering with her mother’s Indian healing or peyote practices.

Sanapia was also raised with the help of her maternal grandmother, who made sure Sanapia learned the old ways and old stories. As a result, Sanapia was exposed to the Christian ideas of her father, her uncle’s peyote practices, and her mother’s vision quests as an eagle doctor.

Eagle doctors identified the eagle as their source of power. According to Sanapia’s account of the origin of eagle doctors, a stingy old woman’s grandson turned himself into an eagle after his grandmother refused to give him food. He then flew into the sky and dropped a feather with the promise that whoever found it would have his help whenever he or she needed it to help other people.

Training as an Eagle Doctor is a long, drawn out process and involves many principles

At the age of seven, Sanapia began attending Cache Creek Mission School in southern Oklahoma. Her attendance at the school marked her first prolonged contact with white society. During her summer vacations, she learned to identify herbal medicines as part of her training to become a medicine woman.

At the age of 14, Sanapia left school. She spent the next three years studying with her mother and uncle, acquiring the knowledge of an eagle doctor. Sanapia also learned the rituals associated with the collection of certain plants and methods for turning the plants into usable medicine. She was taught to administer the medicines and to diagnose and treat illnesses. She also had long talks with her mother and uncle about the proper deportment of a doctor. By the time she was 17, she had all the skills, basic knowledge, and supernatural powers she would need to become a medicine woman.

During her training, Sanapia was watched over by her mother, her maternal uncle, her grandmother, and her paternal grandfather. Each of these individuals had to give Sanapia his or her blessing before she would be allowed to practice. While her mother assumed responsibility for Sanapia’s training as a doctor, her maternal grandmother and paternal grandfather taught her the proper system of values, morals, and ethics. Her uncle named her “Sanapia,” which means “Memory Woman” so she would never forget her duties.

The eagle doctor’s powers were believed to be concentrated in the doctor’s hands and mouth. In the first phase of power transmission, Sanapia’s mother transferred live coals into her daughters’ hand without burning her. Then her mother drew two eagle feathers across Sanipia’s mouth. In the second phase, her mother inserted an “eagle egg” into Sanapia’s stomach. In the next phase, Sanapia acquired her medicine song. The culmination of Sanapia’s training as an eagle doctor was her participation in a vision quest—four days and nights of solitary meditation.

After Sanapia’s mother explained to her what was involved in the vision quest, including encounters with supernatural spirits, Sanapia was too frightened to go through with it. Although she spent the days of the quest sitting on the hill where her mother had sent her, she returned to her house at night and slept under the front porch. In the morning, she would go back to the hill without her mother or uncle knowing what she had done. Sanapia later attributed her suffering as a young woman to this deception.

However, according to Comanche beliefs, a great healer must first suffer great pain themselves, before they can alleviate the pain of others. Also, eagle doctors do not begin to practice medicine in earnest until after menopause, so that they might mature and gain the knowledge and wisdom that comes with life’s lessons.

Sanapia’s Personal Trials

Having completed her training, Sanapia was considered ready for marriage. Her husband, a friend of her brother, was picked out by her mother. While Sanapia had no objections to the marriage, she was not in love with her spouse. After giving birth to a son, Sanapia left her husband at the urging of her mother. Within a year she was married again, to a husband she stayed with her until his death in the 1930s. Her second marriage produced a son and daughter.

Following the death of her second husband, Sanapia drank excessively, engaged in promiscuous sex, and exhibited violent tantrums. She also acquired a taste for gambling. Informants attributed Sanapia’s behavior at this time to her grief at the loss of her husband. Sanapia later referred to this time as her “roughing-it-out” period. During this phase of her life, one of Sanapia’s sisters asked her to heal her sick child. The child recovered, and Sanapia took the recovery as a sign that she should begin doctoring.

Some time around 1945, Sanapia married for the third time. She abandoned her problematic behavior and began doctoring seriously. Doctors were expected to lead exemplary lives, and any bad behavior was thought to bring disgrace on the doctor and on her medicine; in the worst case, it could even cause the doctor’s death.

The doctor was expected to be always accessible and was not permitted to refuse to treat anyone. The doctor was not supposed to boast of her powers; to do so would be to deny that the doctor’s power was a gift. The doctor was not allowed to approach a patient with the offer of a cure but was to wait for the patient to come to her. The amount of payment for services rendered was always left up to the patient.

After Sanapia began her healing practice, she began to have “real” dreams, which she distinguished from ordinary dreams by their power to change her behavior. These dreams frequently dealt with the peyote ritual. But Sanapia considered the power of peyote subordinate to the power possessed by the spirits of her mother and uncle. She considered peyote a gift of the Christian God to the Indian people.

Ghosts are the spirits of evil persons who can cause sickness

Sanapia felt that ghosts were probably the spirits of evil persons who had died and who were destined to wander the earth forever. The ghosts were believed to be jealous of the living. (The spirits of good people who had died were believed to reside in another realm.) According to Comanche beliefs, ghosts had the power to deform their victims by causing facial contractions or hand and arm paralysis. Ghosts were believed to attack people when the victims were outside and alone at night. According to Sanapia, ghost sickness was called “stroke” by white people, but she nevertheless made a distinction between the two ailments and would not treat a stroke victim.

According to David E. Jones, writing in Sanapia: Comanche Medicine Woman, a more closely drawn analysis suggests that ghost sickness actually corresponds to Bell’s Palsy, a paralysis of the muscles on one side of the face. Bell’s palsy, which results from an inflammation of the facial nerve, has a sudden onset that typically occurs at the time of awakening. The modern treatment may involve facial massage. Although Bell’s palsy is the most common cause of facial paralysis, its cause is unknown.

In treating ghost sickness, Sanapia initially had her patient bathe in a stream. Following prayers in which she asked the eagle to help heal her patient, Sanapia “smoked” the patient with cedar smoke. She then chewed recumbent milkweed and applied it to the parts of the patient’s body that exhibited the ghost sickness. She then began sucking on the contorted part of the patient’s face to draw out the sickness.

If the patient had not responded to three treatments by the end of the first day, Sanapia called a peyote meeting, and the patient was given a tea made from the peyote plant. The tea was also applied to the patient’s face, head, and hands. Applications of sweet sage and charcoal from the peyote drum followed.

Sanapia’s last resort was to invoke the intercession of the medicine eagle. To do so, she sang her medicine song repeatedly until she felt the spirits had come to her. At that point, she returned to the patient and continued doctoring, using only her medicine feather and smoke. She did not touch the patient at this point, for fear that she might kill him. By this time, the treatment would have lasted three days.

Sanapia’s pharmacopoeia consisted of both botanical and non-botanical medicines.

Botanical cures I Sanapia’s medicine kit included red cedar to dispel the influence of ghosts; sneezeweed to treat heart palpitations, low blood pressure and congestion; mescal bean for ear problems; rye grass for the treatment of cataracts; prickly ash to treat fever; iris for colds, upset stomachs and sore throats; gray sage for insect bites; sweet sage for use in the sucking ceremony; recumbent milkweed for ghost sickness, broken bones, and menstrual cramps; and broomweed for treatment of skin rashes. Peyote was Sanapia’s medicine of general use; it was employed in the treatment of any type of illness, and she kept several peyote buttons with her at all times.

Non-botanical medicines included crow feathers to protect against ghosts; slivers of glass to make incisions; a piece of cow horn used in sucking sickness from the bodies of her patients; charcoal from a peyote drum to retard the spread of pain and swelling; white otter fur and porcupine quills to treat infants; fossilized bone to treat wounds and infections; a Bible to help in her quest for power; a medicine feather from a golden eagle to fan her patients; beef fat to treat burns; mouth wash to kill poisons that entered her mouth while sucking, and red paint for treating ghost sickness.

According to the doctoring tradition of her people, the medicine power needed to be transferred to someone willing and worthy of the responsibility. It is unclear whether or not Sanapia forwarded her power to a successor. Perhaps out of a concern that she would be unable to pass her power on to the next generation, Sanapia allowed anthropologist David E. Jones to record the details of her life and the medicine tradition beginning in 1967.

Sanapia died in 1984 in Oklahoma and was buried in the Comanche Indian cemetery near Chandler Creek, Oklahoma. She is believed to be the last of the Comanche eagle doctors.