In the 20th century, at least nine American Indians have been among those warriors to be distinguished by receiving the United States’ highest military honor: the Medal of Honor. Given for military heroism “above and beyond the call of duty,” these warriors exhibited extraordinary bravery in the face of the enemy and, in two cases, made the ultimate sacrifice for their country.

The Medal of Honor is the highest U.S. military decoration awarded to individuals who, while serving in the U.S. armed services, have distinguished themselves by conspicuous gallantry and courage at the risk of life, above and beyond the call of duty.

Each recommendation for this decoration must incontestably prove that the act of bravery or self-sacrifice involved obvious risk of life and, if the risk hadn’t been taken, there would be no just grounds for censure. The award is made in the name of congress and is presented by the President of the United States. Originally authorized by congress in 1861, it’s sometimes called the “Congressional Medal of Honor.”

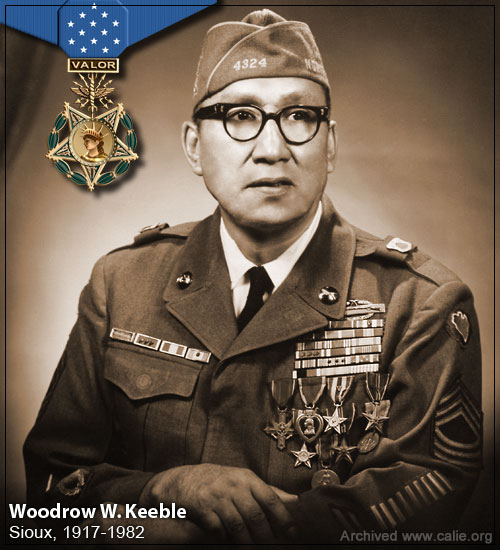

Woodrow W. Keeble (Sioux)

Master Sergeant Woodrow Wilson Keeble (1917-1982) was a U.S. Army National Guard veteran of both World War II and the Korean War. He was a full-blooded member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservation, a Sioux Native American tribe.

Master Sergeant Keeble, a highly-decorated U.S. war veteran, didn’t receive his Medal of Honor until some 16 years after his death. On March 3, 2008, in honor of Master Sgt. Keeble’s gallantry during his service in the Korean War, Kurt Bluedog, Keeble’s great nephew, and Russ Hawkins, a step-son, accepted the award honoring Keeble, the first full-blooded Sioux Indian to receive the Medal of Honor.

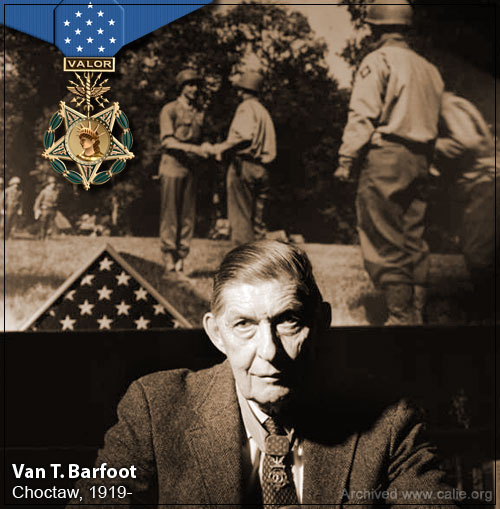

Van T. Barfoot (Chocktaw)

Van T. Barfoot is a Choctaw from Mississippi, and was a Second Lieutenant in the Thunderbirds. On 23 May 1944, during the breakout from Anzio to Rome, Barfoot advanced through a minefield, took out three enemy machine gun emplacements with hand grenades and expert fire from his Thompson submachine gun,and captured 17 German soldiers. Later that same day, he picked up a bazooka, took on and destroyed one of the three advancing Mark VI tanks that German commanders ordered in to spearhead their fierce heavy-armored counter attack on Barfoot’s platoon position in an unsuccessful effort to retake their lost machinegun positions.

As the tank crew members dismounted their disabled tank, Sgt. Barfoot killed three of the German soldiers outright with his tommy gun. Barfoot then continued further into enemy terrain and destroyed a recently abandoned German fieldpiece with a demolition charge placed in the breech. While returning to his platoon position, Sgt. Barfoot, though greatly fatigued by his Herculean efforts, assisted two of his seriously wounded men 1,700 yards to a position of safety. Barfoot is also credited with capturing and bringing back 17 German prisoners of war (POWs) to his platoon position that day.

Mr. Barfoot served in the WW2, Korean and Vietnam wars…then his neighborhood association told the 90-year-old warrior to take down his flag pole. His local neighborhood association quibbled over how the famous 90-year-old war hero chose to fly the American flag outside his suburban Virginia home.

It seems the rules stated a flag may be flown on a house-mounted bracket, but, for decorum, items such as Barfoot’s 21-foot flagpole were socially unsuitable. Barfoot had been previously denied a permit for a flagpole — he erected it anyway despite the permit issue — and then he ended up facing court action unless he took it down.

After the story made national TV news headlines, the neighborhood association rethought its position and agreed to indulge the old hero.

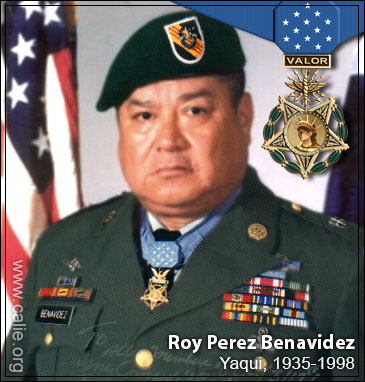

Roy P. Benavidez (Yaqui)

Master Sergeant (then Staff Sergeant) Roy P. Benavidez United States Army, who distinguished himself by a series of daring and extremely valorous actions on 2 May 1968 while assigned to Detachment B56, 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces, Republic of Vietnam.

Master Sergeant (then Staff Sergeant) Roy P. Benavidez United States Army, who distinguished himself by a series of daring and extremely valorous actions on 2 May 1968 while assigned to Detachment B56, 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces, Republic of Vietnam.

On the morning of 2 May 1968, a 12-man Special Forces Reconnaissance Team was inserted by helicopters in a dense jungle area west of Loc Ninh, Vietnam to gather intelligence information about confirmed large-scale enemy activity. This area was controlled and routinely patrolled by the North Vietnamese Army. After a short period of time on the ground, the team met heavy enemy resistance, and requested emergency extraction.

Three helicopters attempted extraction, but were unable to land due to intense enemy small arms and anti-aircraft fire. Sergeant Benavidez was at the Forward Operating Base in Loc Ninh monitoring the operation by radio when these helicopters returned to off-load wounded crewmembers and to assess aircraft damage.

Sergeant Benavidez voluntarily boarded a returning aircraft to assist in another extraction attempt. Realizing that all the team members were either dead or wounded and unable to move to the pickup zone, he directed the aircraft to a nearby clearing where he jumped from the hovering helicopter, and ran approximately 75 meters under withering small arms fire to the crippled team.

Prior to reaching the team’s position he was wounded in his right leg, face, and head. Despite these painful injuries, he took charge, repositioning the team members and directing their fire to facilitate the landing of an extraction aircraft, and the loading of wounded and dead team members.

He then threw smoke canisters to direct the aircraft to the team’s position. Despite his severe wounds and under intense enemy fire, he carried and dragged half of the wounded team members to the awaiting aircraft. He then provided protective fire by running alongside the aircraft as it moved to pick up the remaining team members.

As the enemy’s fire intensified, he hurried to recover the body and classified documents on the dead team leader. When he reached the leader’s body, Sergeant Benavidez was severely wounded by small arms fire in the abdomen and grenade fragments in his back. At nearly the same moment, the aircraft pilot was mortally wounded, and his helicopter crashed.

Although in extremely critical condition due to his multiple wounds, Sergeant Benavidez secured the classified documents and made his way back to the wreckage, where he aided the wounded out of the overturned aircraft, and gathered the stunned survivors into a defensive perimeter. Under increasing enemy automatic weapons and grenade fire, he moved around the perimeter distributing water and ammunition to his weary men, reinstilling in them a will to live and fight.

Facing a buildup of enemy opposition with a beleaguered team, Sergeant Benavidez mustered his strength, began calling in tactical air strikes and directed the fire from supporting gunships to suppress the enemy’s fire and so permit another extraction attempt. He was wounded again in his thigh by small arms fire while administering first aid to a wounded team member just before another extraction helicopter was able to land.

His indomitable spirit kept him going as he began to ferry his comrades to the craft. On his second trip with the wounded, he received additional wounds to his head and arms before killing his adversary. He then continued under devastating fire to carry the wounded to the helicopter.

Upon reaching the aircraft, he spotted and killed two enemy soldiers who were rushing the craft from an angle that prevented the aircraft door gunner from firing upon them. With little strength remaining, he made one last trip to the perimeter to ensure that all classified material had been collected or destroyed, and to bring in the remaining wounded. Only then, in extremely serious condition from numerous wounds and loss of blood, did he allow himself to be pulled into the extraction aircraft.

Sergeant Benavidez’s gallant choice to voluntarily join his comrades who were in critical straits, to expose himself constantly to withering enemy fire, and his refusal to be stopped despite numerous severe wounds, saved the lives of at least eight men. His fearless personal leadership, tenacious devotion to duty, and extremely valorous actions in the face of overwhelming odds were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect the utmost credit on him and the United States Army.

A Navy ship was named after him and a GI Joe doll was modeled after him.

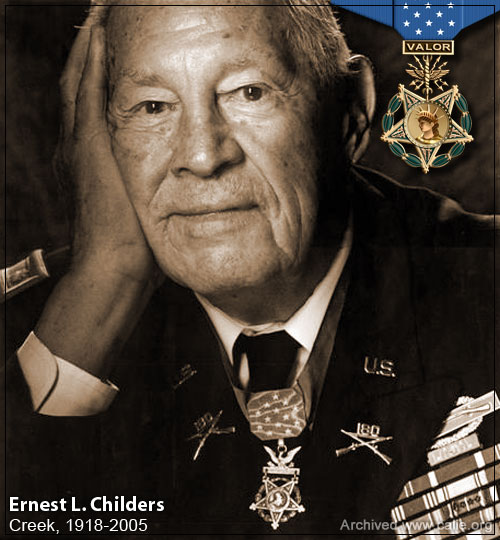

Ernest Childers (Creek)

A Creek American Indian from Oklahoma, and a First Lieutenant with the 45th Infantry Division, Childers received the Medal of Honor for heroic action in 1943 when, up against machine gun fire, he and eight men charged the enemy. Although suffering a broken foot in the assault, Childers ordered covering fire and advanced up the hill, single-handedly killing two snipers, silencing two machine gun nests, and capturing an enemy mortar observer.

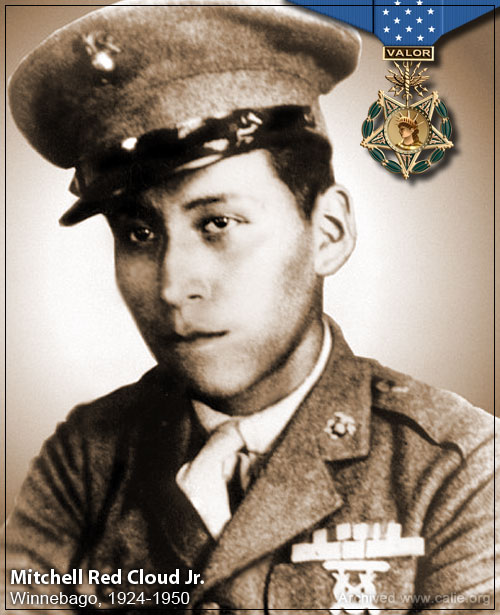

Mitchell Red Cloud Jr. (Winnebago)

A Winnebago from Wisconsin, and a Corporal in Company E., 19th Infantry Regiment in Korea. On 5 November 1950, Red Cloud was on a ridge guarding his company command post when he was surprised by Chinese communist forces. He sounded the alarm and stayed in his position firing his automatic rifle and point-blank to check the assault.

This gave his company time to consolidate their defenses. After being severely wounded by enemy fire, he refused assistance and continued firing upon the enemy until he was fatally wounded. His heroic action prevented the enemy from overrunning his company’s position and gained time for evacuation of the wounded.

Charles George (Cherokee)

Charles George was a Cherokee from North Carolina, and Private First Class in Korea when he was killed on 30 November 1952.

During battle, George threw himself upon a grenade and smothered it with his body. In doing so, he sacrificed his own life but saved the lives of his comrades.

For this brave and selfless act, George was posthumously award the Medal of Honor in 1954.

Ernest Edwin Evans (Cherokee-Creek)

A Cherokee/Creek from Oklahoma, during the Battle for Leyte Gulf, 24-26 October 1944, Commander of the USS Johnston, he formed a part of the screen for escort aircraft carriers of the SEVENTH Fleet which on 25 October encountered off Samar the Center Force of the Japanese Fleet after it had transited San Bernardino Strait during the night of 24-25 October.

The USS Johnston waged a gallant fight against heavy Japanese fleet units but was sunk by the enemy ships. Lieutenant Commander Evans was awarded the Navy Cross, later recalled and replaced by the Medal of Honor, awarded posthumously by United States Congress.

In addition to the Medal of Honor, the Bronze Star Medal, Purple Heart Medal and Presidential Unit Citation Ribbon, Commander Evans had the China Service Medal, American Defense Medal, Fleet Clasp, and was entitled to the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with six engagement stars, the World War II Victory Medal, and the Philippine Defense and Liberation Ribbons with one star.

A U.S. Navy destroyer war ship, the USS Evans (DE-1023), was named in honor of Commander Evans.

Jack C. Montgomery (Cherokee)

A Cherokee from Oklahoma, and a First Lieutenant with the 45th Infantry Division Thunderbirds. On 22 February 1944, near Padiglione, Italy, Montgomery’s rifle platoon was under fire by three echelons of enemy forces, when he single-handedly attacked all three positions, taking prisoners in the process.

As a result of his courage, Montgomery’s actions demoralized the enemy and inspired his men to defeat the Axis troops.

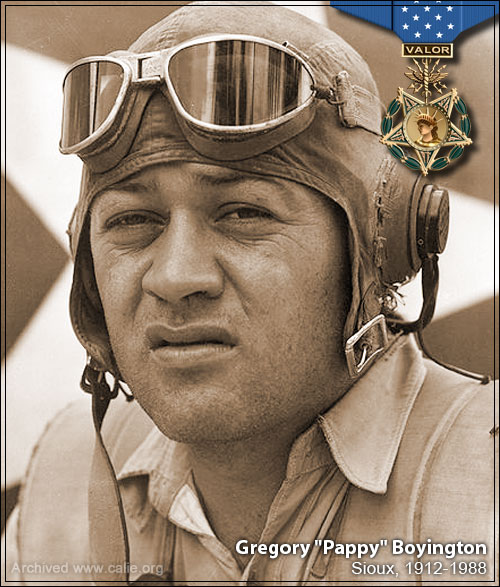

Pappy Boyington (Sioux)

Pappy Boyington was a highly decorated American combat pilot who was a United States Marine Corps fighter ace during World War II. He received both the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross.

Pappy Boyington served as a fighter pilot in both the US Navy and the Marines, and achieved the rank of Colonel in the Marines.

Boyington was initially a P-40 Warhawk combat pilot with the legendary “Flying Tigers” (1st American Volunteer Group) in the Republic of China Air Force in Burma at the end of 1941 and part of 1942; during the military conflict between China and Japan, and the beginning of World War II.

Boyington was shot down during a WWII combat mission and declared missing in action. He had been picked up by a Japanese submarine and became a prisoner of war. According to Boyington’s autobiography, he was never accorded official P.O.W. status by the Japanese and his captivity was not reported to the Red Cross. He spent the rest of the war, some 20 months, in Japanese prison camps.