The French and Indian War began in 1754 as British and French forces clashed in the wilderness of North America. Two years later, the conflict spread to Europe where it became known as the Seven Years’ War.

In many ways an extension of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), the conflict saw a shifting of alliances with Britain joining with Prussia while France allied with Austria.

The first war fought on a global scale, it saw battles in Europe, North America, Africa, India, and the Pacific. Concluding in 1763, the French & Indian / Seven Years’ War cost France the bulk of its North American territory.

The Situation in North America

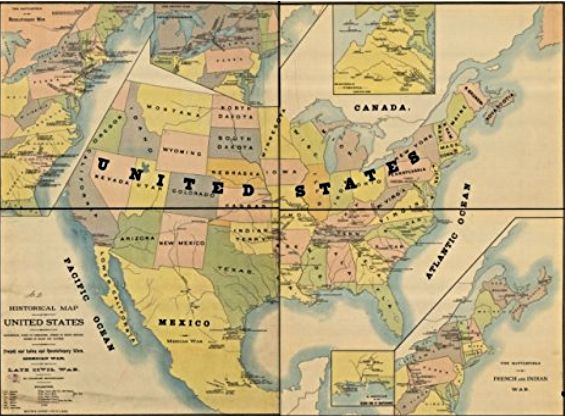

Buy this 1890 Historical map of the United States indicating battlefields, names of

commanders, number of troops engaged, number of killed and captured during French and

Indian and Revolutionary wars, Mexican War, and the late Civil War.Known as King George’s War in the North American colonies, the conflict had seen colonial troops mount a daring and successful attempt to capture the French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island. The return of the fortress was a point of concern and ire among the colonists when peace was declared.

While the British colonies occupied much of the Atlantic coast, they were effectively surrounded by French lands to the north and west. To control this vast expanse of territory extending from the mouth of the St.Lawrence down to the Mississippi delta, the French built a string of outposts and forts from the western Great Lakes down to the Gulf of Mexico.

The location of this line left a wide area between the French garrisons and the crest of the Appalachian Mountains to the east. This territory, largely drained by the Ohio River, was claimed by the French but was increasingly filling with British settlers as they pushed over the mountains.

This was largely due to the burgeoning population of the British colonies which in 1754 contained around 1,160,000 white inhabitants as well as another 300,000 slaves. These numbers dwarfed the population of New France which totaled around 55,000 in present-day Canada and another 25,000 in other areas.

Caught between these rival empires were the Native Americans, of which the Iroquois Confederacy was the most powerful. Initially consisting of the Mohawk, Seneca, Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga, the group later became the Six Nations with the addition of the Tuscarora.

United, their territory extended between the French and British from the upper reaches of the Hudson River west into the Ohio basin. While officially neutral, the Six Nations were courted by both European powers and frequently traded with whichever side was convenient.

The French Stake Their Claim

In an effort to assert their control over the Ohio Country, the governor of New France, the Marquis de La Galissonière, dispatched Captain Pierre Joseph Céloron de Blainville in 1749 to restore and mark the border.

Departing Montreal, his expedition of around 270 men moved through present-day western New York and Pennsylvania. As it progressed, he placed lead plates announcing France’s claim to the land at the mouths of several creeks and rivers.

Reaching Logstown on the Ohio River, he evicted several British traders and admonished the Native Americans against trading with anyone but the French. After passing present-day Cincinnati, he turned north and returned to Montreal.

Despite Céloron’s expedition, British settlers continued to push over the mountains, especially those from Virginia. This was backed by colonial government of Virginia who granted land in the Ohio Country to the Ohio Land Company. Dispatching surveyor Christopher Gist, the company began scouting the region and received permission from the Native Americans to fortify the trading post at Logstown.

Aware of these increasing British incursions, the new governor of New France, the Marquis de Duquesne, sent Paul Marin de la Malgue to the area with 2,000 men in 1753 to built a new series of forts.

The first of these was built at Presque Isle on Lake Erie (Erie, PA), with another twelve miles south at French Creek (Fort Le Boeuf). Pushing down the Allegheny River, Marin captured the trading post at Venango and built Fort Machault. The Iroquois were alarmed by these actions and complained to British Indian agent Sir William Johnson.

The British Response

As Marin was constructing his outposts, the lieutenant governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, became increasingly concerned. Lobbying for the building of a similar string of forts, he received permission provided that he first assert British rights to the French. To do so, he dispatched young Major George Washington on October 31, 1753.

Traveling north with Gist, Washington paused at the Forks of the Ohio where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers came together to form the Ohio. Reaching Logstown, the party was joined by Tanaghrisson (Half King), a Seneca chief who disliked the French.

The party ultimately reached Fort Le Boeuf on December 12 and Washington met with Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre. Presenting an order from Dinwiddie requiring the French to depart, Washington received a negative reply from Legarduer. Returning to Virginia, Washington informed Dinwiddie of the situation.

First Shots Are Fired

Prior to Washington’s return, Dinwiddie dispatched a small party of men under William Trent to begin building a fort at the Forks of the Ohio. Arriving in February 1754, they constructed a small stockade, but were forced out by a French force led by Claude-Pierre Pecaudy de Contrecoeur in April. Taking possession of the site, they began constructing a new base dubbed Fort Duquesne.

After presenting his report in Williamsburg, Washington was ordered to return to the forks with a larger force to aid Trent in his work. Learning of the French force en route, he pressed on with the support of Tanaghrisson. Arriving at Great Meadows, approximately 35 miles south of Fort Duquesne, Washington halted as he knew he was badly outnumbered.

Establishing a base camp in the meadows, Washington began exploring the area while waiting for reinforcements. Three days later, he was alerted to the approach of a French scouting party.

Assessing the situation, Washington was advised to attack by Tanaghrisson. Agreeing, Washington and approximately 40 of his men marched through the night and foul weather. Finding the French camped in a narrow valley, the British surrounded their position and opened fire.

In the resulting Battle of Jumonville Glen, Washington’s men killed 10 French soldiers and captured 21, including their commander Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville.

After the battle, as Washington was interrogating Jumonville, Tanaghrisson walked up and struck the French officer in the head killing him.

Anticipating a French counterattack, Washington fell back to Great Meadows and built a crude stockade known as Fort Necessity. Though reinforced, he remained outnumbered when Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers arrived at Great Meadows with 700 men on July 1.

Beginning the Battle of Great Meadows, Coulon was able to quickly compel Washington to surrender. Allowed to withdraw with his men, Washington departed the area on July 4.

The Albany Congress

While events were unfolding on the frontier, the northern colonies were becoming increasingly concerned about French activities. Gathering in the summer of 1754, representatives from the various British colonies came together in Albany to discuss plans for mutual defense and to renew their agreements with the Iroquois which were known as the Covenant Chain.

In the talks, Iroquois representative Chief Hendrick requested the re-appointment of Johnson and expressed concern over British and French activities. His concerns were largely placated and the Six Nations representatives departed after the ritual presentation of presents.

The representatives also debated a plan for uniting the colonies under a single government for mutual defense and administration. Dubbed the Albany Plan of Union, it required an Act of Parliament to implement as well as the support of the colonial legislatures. The brainchild of Benjamin Franklin, the plan received little support among the individual legislatures and was not addressed by Parliament in London.

British Plans for 1755

Though war with France had not been formally declared, the British government, led by the Duke of Newcastle, made plans for a series of campaigns in 1755 designed to reduce French influence in North America.

While Major General Edward Braddock was to lead a large force against Fort Duquesne, Sir William Johnson was to advance up Lakes George and Champlain to capture Fort St. Frédéric (Crown Point).

In addition to these efforts, Governor William Shirley, made a major general, was tasked with reinforcing Fort Oswego in western New York before moving against Fort Niagara. To the east, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Monckton was ordered to capture Fort Beauséjour on the frontier between Nova Scotia and Acadia.

Braddock’s Failure

Designated the commander-in-chief of British forces in America, Braddock was convinced by Dinwiddie to mount his expedition against Fort Duquesne from Virginia as the resulting military road would benefit the lieutenant governor’s business interests.

Assembling a force of around 2,400 men, he established his base at Fort Cumberland, MD before pushing north on May 29. Accompanied by Washington, the army followed his earlier route towards the Forks of the Ohio. Slowly plodding through the wilderness as his men cut a road for the wagons and artillery, Braddock sought to increase his speed by rushing forward with a light column of 1,300 men.

Alerted to Braddock’s approach, the French dispatched a mixed force of infantry and Native Americans from Fort Duquesne under the command of Captains Liénard de Beaujeu and Captain Jean-Daniel Dumas. On July 9, 1755, they attacked the British in the Battle of the Monongahela.

In the fighting, Braddock was mortally wounded and his army routed. Defeated, the British column fell back to Great Meadows before retreating towards Philadelphia.

To the east, Monckton had success in his operations against Fort Beauséjour. Beginning his offensive on June 3, he was in position to begin shelling the fort ten days later. On July 16, British artillery breached the fort’s walls and the garrison surrendered.

The capture of the fort was marred later that year when Nova Scotia’s governor, Charles Lawrence, began expelling the French-speaking Acadian population from the area.

In western New York, Shirley moved through the wilderness and arrived at Oswego on August 17. Approximately 150 miles short of his goal, he paused amid reports that French strength was massing at Fort Frontenac across Lake Ontario. Hesitant to push on, he elected to halt for the season and began enlarging and reinforcing Fort Oswego.

As the British campaigns were moving forward, the French benefited from knowledge of the enemy’s plans as they had captured Braddock’s letters at Monongahela.

This intelligence led to French commander Baron Dieskau moving down Lake Champlain to block Johnson rather than embarking on a campaign against Shirley.

Seeking to attack Johnson’s supply lines, Dieskau moved up (south) Lake George and scouted Fort Lyman (Edward). On September 8, his force clashed with Johnson’s at the Battle of Lake George. Dieskau was wounded and captured in the fighting and the French were forced to withdraw.

As it was late in the season, Johnson remained at the southern end of Lake George and began construction of Fort William Henry. Moving down the lake, the French retreated to Ticonderoga Point on Lake Champlain where they completed construction of Fort Carillon. With these movements, campaigning in 1755 effectively ended.

What had begun as a frontier war in 1754, would explode into a global conflict in 1756.

War in the Wilderness – 1754-1755

In the early 1750s, the British colonies in North America began pushing west over the Allegheny Mountains. This brought them into conflict with the French who claimed this territory as their own.

In an effort to assert a claim to this area, the Governor of Virginia dispatched men to build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio. These were later supported by militia led by Lt. Col. George Washington.

Encountering the French, Washington was forced to surrender at Fort Necessity.

Angered, the British government planned aggressive campaigns for 1755. These saw a second expedition to the Ohio badly defeated at the Battle of the Monongahela, while other British troops won victories at Lake George and Fort Beauséjour.

In 1748, the War of the Austrian Succession came to a conclusion with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. During the course of the eight-year conflict, France, Prussia, and Spain had squared off against Austria, Britain, Russia, and the Low Countries.

When the treaty was signed, many of the underlying issues of the conflict remained unresolved including those of expanding empires and Prussia’s seizure of Silesia.

In the negotiations, many captured colonial outposts were returned to their original owners, such as Madras to the British and Louisbourg to the French, while the trading rivalries that had helped cause the war were ignored. Due to this relatively inconclusive result, the treaty was considered by many to a “peace without victory” with international tensions remaining high among the recent combatants.

1756-1757: War on a Global Scale

While the British had hoped to limit the conflict to North America, this was dashed when the French invaded Minorca in 1756. Subsequent operations saw the British ally with the Prussians against the French, Austrians, and Russians.

Quickly invading Saxony, Frederick the Great (left) defeated the Austrians at Lobositz that October. The following year saw Prussia come under heavy pressure after the Duke of Cumberland’s Hanoverian army was defeated by the French at the Battle of Hastenbeck.

Despite this, Frederick was able to rescue the situation with key victories at Rossbach and Leuthen. Overseas, the British were defeated in New York at the Siege of Fort William Henry, but won a decisive victory at the Battle of Plassey in India.

Changes in Command

In the wake of Major General Edward Braddock’s death at the Battle of Monongahela in July 1755, command of British forces in North America passed to Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts.

Unable to come to an accord with his commanders, he was replaced in January 1756, when the Duke of Newcastle, heading the British government, appointed Lord Loudoun to the post with Major General James Abercrombie as his second in command.

Changes were also afoot to the north where Major General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, Marquis de Saint-Veran arrived in May with a small contingent of reinforcements and orders to assume overall command of French forces. This appointment angered the Marquis de Vaudreuil, governor of New France (Canada), as he had designs on the post.

In the winter of 1756, prior to Montcalm’s arrival, Vaudreuil ordered a series of successful raids against the British supply lines leading to Fort Oswego. These destroyed large quantities of supplies and hampered British plans for campaigning on Lake Ontario later that year.

Arriving in Albany, NY in July, Abercrombie proved a highly cautious commander and refused to take action without Loudoun’s approval. This was countered by Montcalm who proved highly aggressive. Moving to Fort Carillon on Lake Champlain he feinted an advance south before shifting west to conduct an attack on Fort Oswego.

Moving against the fort in mid-August, he compelled its surrender and effectively eliminated the British presence on Lake Ontario.

Shifting Alliances

While fighting raged in the colonies, Newcastle sought to avoid a general conflict in Europe. Due to changing national interests on the Continent, the systems of alliances that had been in place for decades began to decay as each country sought to safeguard their interests.

While Newcastle wished fight a decisive colonial war against the French, he was hampered by the need to protect the Electorate of Hanover which had ties to the British royal family. In seeking a new ally to guarantee the safety of Hanover, he found a willing partner in Prussia.

A former British adversary, Prussia wished to retain the lands (namely Silesia) it had gained during the War of the Austrian Succession. Concerned about the possibility of a large alliance against his nation, King Frederick II (the Great) began making overtures to London in May 1755.

Subsequent negotiations led to the Convention of Westminster which was signed on January 15, 1756. Defensive in nature, this agreement called for Prussia to protect Hanover from the French in exchange for the British withholding aid from Austria in any conflict over Silesia.

A long-time ally of Britain, Austria was angered by the Convention and stepped up talks with France. Though reluctant to join with Austria, Louis XV agreed to a defensive alliance in the wake of increasing hostilities with Britain.

Signed on May 1, 1756, the Treaty of Versailles saw the two nations agree to provide aid and troops should one be attacked by a third party.

In addition, Austria agreed not to aid Britain in any colonial conflicts. Operating on the fringe of these talks was Russia which was eager to contain Prussian expansionism while also improving their position in Poland. While not a signatory of the treaty, Empress Elizabeth’s government was sympathetic to the French and Austrians.

War Is Declared

While Newcastle worked to limit the conflict, the French moved to expand it. Forming a large force at Toulon, the French fleet began an attack on British-held Minorca in April 1756.

In an effort to relieve the garrison, the Royal Navy dispatched a force to the area under the command of Admiral John Byng. Beset by delays and with ships in ill-repair, Byng reached Minorca and clashed with a French fleet of equal size on May 20.

Though the action was inconclusive, Byng’s ships took substantial damage and in a resulting council of war his officers agreed that the fleet should return to Gibraltar.

Under increasing pressure, the British garrison on Minorca surrendered on May 28. In a tragic turn of events, Byng was charged with not doing his utmost to relieve the island and after a court-martial was executed. In response to the attack on Minorca, Britain officially declared war on May 17, nearly two years after the first shots in North America.

Frederick Moves

As war between Britain and France was formalized, Frederick became increasingly concerned about France, Austria, and Russian moving against Prussia. Alerted that Austria and Russia were mobilizing, he did likewise.

In a preemptive move, Frederick’s highly disciplined forces began an invasion of Saxony on August 29 which was aligned with his enemies.

Catching the Saxons by surprise, he cornered their small army at Pirna. Moving to aid the Saxons, an Austrian army under Marshal Maximilian von Browne marched towards the border. Advancing to meet the enemy, Frederick attacked Browne at the Battle of Lobositz on October 1. In heavy fighting, the Prussians were able to compel the Austrians to retreat.

Though the Austrians continued attempts to relieve the Saxons they were in vain and the forces at Pirna surrendered two weeks later.

Though Frederick had intended the invasion of Saxony to serve as a warning to his adversaries, it only worked to further unite them.

The military events of 1756 effectively eliminated the hope that a large-scale war could be avoided. Accepting this inevitability, both sides began re-working their defensive alliances into ones that were more offensive in nature.

Though already allied in spirit, Russia officially joined with France and Austria on January 11, 1757, when it became the third signatory of the Treaty of Versailles.

British Setbacks in North America

Largely inactive in 1756, Lord Loudoun remained inert through the opening months of 1757. In April he received orders to mount an expedition against the French fortress city of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island. An important base for the French navy, the city also guarded the approaches to the Saint Lawrence River and the heartland of New France.

Stripping troops from the New York frontier, he was able to assemble a strike force at Halifax by early July. While waiting for a Royal Navy squadron, Loudoun received intelligence that the French had massed 22 ships of the line and around 7,000 men at Louisbourg.

Feeling that he lacked the numbers to defeat such a force, Loudoun abandoned the expedition and began returning his men to New York.

While Loudoun was shifting men up and down the coast, the industrious Montcalm had moved to the offensive. Gathering around 8,000 regulars, militia, and Native American warriors, he pushed south across Lake George with the goal of taking Fort William Henry.

Held by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Munro and 2,200 men, the fort possessed 17 guns. By August 3, Montcalm had surrounded the fort and laid siege. Though Munro requested aid from Fort Edward to the south it was not forthcoming as the commander there believed the French had around 12,000 men.

Under heavy pressure, Munro was forced to surrender on August 9. Though Munro’s garrison was paroled and guaranteed safe conduct to Fort Edward, they were attacked by Montcalm’s Native Americans as they departed with over 100 men, women, and children killed. The defeat eliminated the British presence on Lake George.

Defeat in Hanover

With Frederick’s incursion into Saxony the Treaty of Versailles was activated and the French began making preparations to strike Hanover and western Prussia. Informing the British of French intentions, Frederick estimated that the enemy would attack with around 50,000 men.

Facing recruitment issues and war aims that called for a colonies-first approach, London did not wish to deploy large numbers of men to the Continent. As a result, Frederick suggested that the Hanoverian and Hessian forces that had been summoned to Britain earlier in the conflict be returned and augmented by Prussian and other German troops.

This plan for an “Army of Observation” was agreed to and effectively saw the British pay for an army to defend Hanover that included no British soldiers. On March 30, 1757, the Duke of Cumberland, son of King George II, was assigned to lead the allied army.

Opposing Cumberland were around 100,000 men under the direction of the Duc d’Estrées. In early April the French crossed the Rhine and pushed towards Wesel. As the d’Estrées moved, the French, Austrians, and Russians formalized the Second Treaty of Versailles which was an offensive agreement designed to crush Prussia.

Outnumbered, Cumberland continued to fall back until early June when he attempted a stand at Brackwede. Flanked out of this position, the Army of Observation was compelled to retreat. Turning, Cumberland next assumed a strong defensive position at Hastenbeck.

On July 26, the French attacked and after an intense, confused battle both sides withdrew. Having ceded most of Hanover in the course of the campaign, Cumberland felt compelled to enter into the Convention of Klosterzeven which de-mobilized his army and withdrew Hanover from the war.

This agreement proved highly unpopular with Frederick as it greatly weakened his western frontier. The defeat and convention effectively ended Cumberland’s military career. In an effort to draw French troops away from the front, the Royal Navy planned attacks on the French coast.

Assembling troops on the Isle of Wight, an attempt was made to raid Rochefort in September. While the Isle d’Aix was captured, word of French reinforcements in Rochefort led to the attack being abandoned.

Frederick in Bohemia

Having won a victory in Saxony the year before, Frederick looked to invade Bohemia in 1757 with the goal of crushing the Austrian army. Crossing the border with 116,000 men divided into four forces, Frederick drove on Prague where he met the Austrians who were commanded by Browne and Prince Charles of Lorraine.

In a hard fought engagement, the Prussians drove the Austrians from the field and forced many to flee into the city.

Having won in the field, Frederick laid siege to the city on May 29. In an effort to recover the situation, a new Austrian 30,000-man force led by Marshal Leopold von Daun was assembled to the east. Dispatching the Duke of Bevern to deal with Daun, Frederick soon followed with additional men.

Meeting near Kolin on June 18, Daun defeated Frederick forcing the Prussians to abandon the siege of Prague and depart Bohemia.

Prussia Under Pressure

Later that summer, Russian forces began to enter the fray. Receiving permission from the King of Poland, who was also the Elector of Saxony, the Russians were able to march across Poland to strike at the province of East Prussia.

Advancing on a broad front, Field Marshal Stephen F.Apraksin’s 55,000-man army drove back Field Marshal Hans von Lehwaldt smaller 32,000-man force. As the Russian moved against the provincial capital of Königsberg, Lehwaldt launched an attack intended to strike the enemy on the march. In the resulting Battle of Gross-Jägersdorf on August 30, the Prussians were defeated and forced to retreat west into Pomerania.

Despite occupying East Prussia, the Russians withdrew to Poland in October, a move which led to Apraksin’s removal.

Having been ousted from Bohemia, Frederick was next required to meet a French threat from the west.

Advancing with 42,000 men, Charles, Prince of Soubise, attacked into Brandenburg with a mixed French and German army. Leaving 30,000 men to protect Silesia, Frederick raced west with 22,000 men. On November 5, the two armies met at the Battle of Rossbach which saw Frederick win a decisive victory. In the fighting, the allied army lost around 10,000 men, while Prussian losses totaled 548.

While Frederick was dealing with Soubise, Austrian forces began invading Silesia and defeated a Prussian army near Breslau. Utilizing interior lines, Frederick shifted 30,000 men east to confront the Austrians under Charles at Leuthen on December 5.

Though outnumbered 2-to-1, Frederick was able to move around the Austrian right flank and, using a tactic known as oblique order, shattered the Austrian army.

The Battle of Leuthen is generally considered Frederick’s masterpiece and saw his army inflict losses totaling around 22,000 while only sustaining approximately 6,400. Having dealt with the major threats facing Prussia, Frederick returned north and defeated an incursion by the Swedes.

In the process, Prussian troops occupied most of Swedish Pomerania. While the initiative rested with Frederick, the year’s battles had badly bled his armies and he needed to rest and refit.

Far Away Fighting

While fighting raged in Europe and North America it also spilled over to the more faraway outposts of the British and French Empires making the conflict the world’s first global war.

In India, the two nations’ trading interests were represented by the French and English East India Companies. In asserting their power, both organizations built their own military forces and recruited additional sepoy units. In 1756, fighting began in Bengal after both sides began reinforcing their trading stations.

This angered the local Nawab, Siraj-ud-Duala, who ordered military preparations to cease. The British refused and in a short time the Nawab’s forces had seized the English East India Company’s stations, including Calcutta.

After taking Fort William in Calcutta, a large number of British prisoners were herded into a tiny prison. Dubbed the “Black Hole of Calcutta,” many died from heat exhaustion and being smothered.

The English East India Company moved quickly to regain its position in Bengal and dispatched forces under Robert Clive from Madras. Carried by four ships of line commanded by Vice Admiral Charles Watson, Clive’s force re-took Calcutta and attacked Hooghly.

After a brief battle with the Nawab’s army on February 4, Clive was able to conclude a treaty which saw all British property returned. Concerned about growing British power in Bengal, the Nawab began corresponding with the French. At this same time, the badly outnumbered Clive began making deals with the Nawab’s officers to overthrow him.

On June 23, Clive moved to attack the Nawab’s army which was now backed by French artillery.

Meeting at the Battle of Plassey, Clive won a stunning victory when the conspirators’ forces remained out of the battle. The victory eliminated French influence in Bengal and the fighting shifted south.

French and Indian War, 1758-1763

Indian Tribes Involved in the French and Indian War