Chief Black Kettle (Mo’ohtavetoo’o) (born ca. 1803, killed November 27, 1868) was a leader of the Southern Cheyenne after 1854. He was known as a peacemaker who accepted numerous treaties to protect his people. He survived the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. He and his wife were among those killed in 1868 at the Battle of Washita River, in a US Army attack on their camp by George Armstrong Custer. They were shot in the back.

Motavato (pronounced Moke-ta-ve-to) was born near the Black Hills of South Dakota sometime about 1803. Nothing is known about his early life until he had moved south in 1832, and joined the Southern Cheyenne who roamed in a vast territory in western Kansas and eastern Colorado.

Motavato (pronounced Moke-ta-ve-to) was born near the Black Hills of South Dakota sometime about 1803. Nothing is known about his early life until he had moved south in 1832, and joined the Southern Cheyenne who roamed in a vast territory in western Kansas and eastern Colorado.

Decades later, after having displayed strong leadership skills, he became chief of the Wuhtapiu group of Cheyenne in 1861. He was also made a chief of the Council of Forty-Four, the central government of all the villages of the Cheyenne tribe.

Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1851

Black Kettle first signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1851. But, the US government was unwilling to control white expansion into the Great Plains, especially after the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush began in 1859. European Americans displaced the Cheyenne from their lands in violation of the treaty, and consumed important resources of water and game. Increasing competition led to armed conflict between the groups.

Treaty of Fort Wise

Black Kettle was a pragmatist who believed that US military power and the number of immigrants were overwhelming. In 1861 he and some of the Arapaho surrendered to the commander of Fort Lyon under the Treaty of Fort Wise, believing he could gain protection for his people.

The treaty was highly unfavorable to the Southern Cheyenne, ceding to the United States most of the lands designated to them by the Fort Laramie treaty. The new reservation was less than one-thirteenth the size of their former reservation.

A significant proportion of Cheyennes opposed this treaty on the grounds that only a minority of Cheyenne chiefs had signed, and without the consent or approval of the rest of the tribe. Many Cheyenne warriors, including the Dog Soldiers would not accept this treaty. They began to attack white settlers and raid farms and wagon trains.

Chief Black Kettle and the Arapaho chiefs led their bands to the new Sand Creek Reservation, a small corner of southeastern Colorado about 40 miles from Fort Lyon. This reservation land was not arable and was located over 200 miles away from the buffalo herds, their major source of meat.

Chief Black Kettle and the Arapaho chiefs led their bands to the new Sand Creek Reservation, a small corner of southeastern Colorado about 40 miles from Fort Lyon. This reservation land was not arable and was located over 200 miles away from the buffalo herds, their major source of meat.

The beginning of the American Civil War in 1861 led to the organization of military forces in Colorado Territory. In March 1862, the Coloradans defeated the Texas Confederate Army in the Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico. Following the battle, the First Regiment of Colorado Volunteers returned to Colorado Territory and were mounted as a home guard under the command of Colonel John Chivington. Chivington and Colorado territorial governor John Evans adopted a hard line against the Indians.

Treaty of Fort Weld

As the Civil War progressed in the east, the number of soldiers in the area was greatly decreased and without protection, the Indians accelerated their attacks. However, the area settlers were enraged and soon formed a volunteer militia which led to the Colorado War of 1864-1865, and one of the most infamous incidents of the Indian Wars – the Sand Creek Massacre.

By the summer of 1864, the situation was at boiling point. Southern Cheyenne Dog Soldiers, along with allied Kiowa and Arapaho bands, raided American settlements for livestock and supplies. Sometimes they took captives, generally only women and children, to adopt into their tribes to replace lost members. In July 1864, Indians killed a family of settlers, an attack which the whites called the Hungate massacre after the family. Pro-war whites displayed the scalped bodies in Denver. Colorado governor John Evans believed tribal chiefs had ordered the attack and were intent on a full-scale war.

Evans issued a proclamation ordering all “Friendly Indians of the Plains” to report to military posts or be considered “hostile.” He sought and gained from the War Department authorization to establish the Third Colorado Cavalry. John Chivington led the unit, composed of “100-daysers,” whose limited term was specifically for fighting against the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

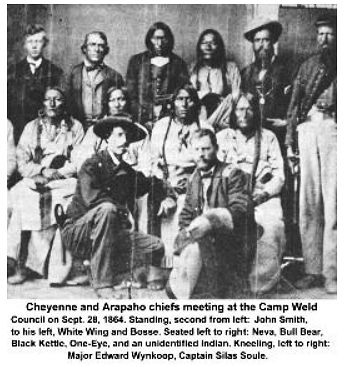

Black Kettle decided to accept Evans’ offer, and entered negotiations. On September 28, he concluded a peace settlement at Fort Weld outside Denver. The agreement assigned the Southern Cheyenne to the Sand Creek reservation and required them to report to Fort Lyon, formerly Fort Wise. Black Kettle believed the agreement would ensure the safety of his people. After he went to the reservation, the commanding officer at the fort was replaced by one who was an ally of Chivington.

Sand Creek Massacre

Ambitious, Chivington felt pressure from Governor Evans to use the Third Colorado Cavalry before their terms expired at the end of 1864. On November 28, Chivington arrived with 700 men at Fort Lyon.

At dawn on November 29, Chivington attacked the Sand Creek reservation. Following Indian agent instructions, Black Kettle flew an American flag and a white flag from his tipi, but the signal was ignored. At one point, he stood in the middle of the encampment waving the white flag above his head.

The Colorado forces killed 163 Cheyenne by shooting or stabbing. They burned down the village encampment and all their winter food supplies perished along with it. About 20 old men were killed, but most of the victims were women and children. Most of the warriors had been out hunting that day.

For months afterward, members of the militia displayed trophies in Denver of their battle, including body parts they had taken for souvenirs.

Though Black Kettle miraculously escaped harm at Sand Creek, his wife was shot several times. He later returned to rescue his severely injured wife, and she survived the multiple gunshot wounds, only to be killed at the Washita Massacre four years later.

Always a peaceful man, Black Kettle continued to counsel peace, even as other Cheyenne struck back with continued raids on wagon trains and nearby ranches.

Black Kettle’s band moves to Kansas

By October 1865, he and other Indian leaders had arranged an uneasy truce on the plains, signing a new treaty that exchanged the Sand Creek Reservation for two reservations in southwestern Kansas, though these did not include their former Kansas hunting grounds.

As Black Kettle led his band to Kansas, many refused to follow, and instead, headed north to join the Northern Cheyenne in Lakota territory. Yet others, ignored the treaty altogether and continued to roam over their ancestral lands. These roaming braves, referred to as Dog Soldiers, soon allied themselves with the Cheyenne war chief, Roman Nose.

The relationship between the two groups is a subject of historical dispute. According to Little Rock, second-in-command of Black Kettle’s village, most of the warriors came back to Black Kettle’s camp after their attacks. White prisoners, including children, were held within his encampment. By this time Black Kettle’s influence was waning, and it is unclear whether he could have stopped the younger warriors’ actions.

The U.S. Government, angered by the Cheyenne’s refusal to obey the treaty soon sent in General William Tecumseh Sherman to force them onto their assigned lands. However, Roman Nose and his followers struck back by continuing to attack so many westward bound pioneers that it soon halted all traffic across western Kansas for a time.

Treaty of Little Arkansas River

Black Kettle moved south and continued to negotiate with US officials. He achieved the Treaty of Little Arkansas River on October 14, 1865. By this document, the US promised “perpetual peace” and lands in reparation for the Sand Creek massacre. However, its practical effect was to dispossess the Cheyenne yet again and require them to move to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Black Kettle’s influence continued to wane.

There, the Indians were promised that they would receive annual provisions of food and supplies.

Medicine Lodge Treaty

Black Kettle was once again among the leaders who signed the treaty – the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867.

However, once he moved his band to the new reservation, the promised provisions were never given and by year’s end, even more of the Cheyenne braves had joined with Roman Nose.

Washita River Massacre

As these renegade Cheyenne continued to raid farms in Kansas and Colorado, General Philip Sheridan once again launched a campaign against the Cheyenne encampments. Seventh Cavalry Commander, George Armstrong Custer, taking the lead in one campaign followed the tracks of a small raiding party to a Cheyenne village on the Washita River.

Well within the boundaries of the Cheyenne reservation, it was Black Kettle’s village. Though a white flag flew above Black Kettle’s tipi, Custer ordered an attack on the village at dawn on November 27, 1868. Both Black Kettle and his wife would die, along with approximately 150 warriors and an estimated 20 or more women and children. The rest of the camp (52 people)were taken as prisoners. The village and all their winter supplies were burned. They slaughtered about 800 Indian horses.

Dying with Black Kettle were the Cheyenne’s hopes of sustaining themselves as an independent people. By the next year, all had been driven from the plains and confined to reservations.

Black Kettle is buried in the Indian Cemetery in Colony, Oklahoma.