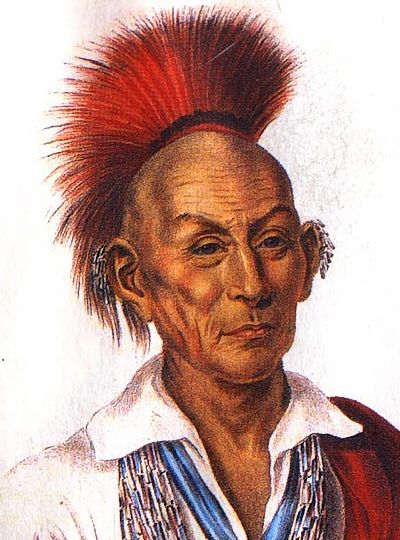

Black Hawk became a war chief because of his prowess as a war leader. Although Black Hawk was never a civil chief, he killed his first man by the time he was 15 years old and was appointed a chief because of his abilities to lead war parties. Before his 18th birthday he had led war parties to victory.

Black Hawk became a war chief because of his prowess as a war leader. Although Black Hawk was never a civil chief, he killed his first man by the time he was 15 years old and was appointed a chief because of his abilities to lead war parties. Before his 18th birthday he had led war parties to victory.

The civil or ceremonial chief of the Sauk tribe was Quashquame. Quashquame is best known as the leader of the 1804 delegation to St. Louis that ceded lands in western Illinois and northeast Missouri to the U.S. government under the supervision of William Henry Harrison. This treaty was disputed, as the Sauk argued the delegation was not authorized to sign treaties and the delegates did not understand what they were signing.

Black Hawk, a frequent visitor to Quashquame’s village, lamented this treaty in his autobiography. The Sauk and Meskwaki delegation had been sent to surrender a murder suspect and make amends for the killing, not to conduct land treaties. The treaty was a primary cause of Sauk displeasure with the U.S. government and caused many Sauk, including Black Hawk, to side with the British during the War of 1812.

Near the end of his captivity in 1833, Black Hawk told his life story to Antoine LeClaire, a government interpreter. Edited by the local reporter J.B. Patterson, Black Hawk’s account was the first Native American autobiography published in the United States.

The Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, or Black Hawk, Embracing the Traditions of his Nation, Various Wars In Which He Has Been Engaged, and His Account of the Cause and General History of the Black Hawk War of 1832, His Surrender, and Travels Through the United States.

Also Life, Death and Burial of the Old Chief, Together with a History of the Black Hawk War was published in 1833 in Cincinnati, Ohio. The book immediately became a best seller.

Death and Burial

After that tour, Black Hawk was transferred back to his nation. He lived with the Sauk along the Iowa River and later the Des Moines River in what is now southeast Iowa. He died on October 3, 1838 after two weeks of illness, and was buried on the farm of his friend James Jordan on the north bank of the Des Moines River in Davis County.

In July 1839, his remains were stolen by James Turner, who prepared his skeleton for exhibition. Black Hawk’s sons Nashashuk and Gamesett went to Governor Robert Lucas of Iowa Territory, who used his influence to bring the bones to security in his offices in Burlington. With the permission of the Chief’s sons, the remains were held by the Burlington Geological and Historical Society. When the Society’s building burned down in 1855, Black Hawk’s remains were destroyed.

An alternative story is that Lucas passed Black Hawk’s bones to a Burlington physician, Enos Lowe, who left them to his partner, Dr. McLaurens. Eventually workers found the bones left by McLaurens after he moved to California. They buried the remains in a potter’s grave in Aspen Grove Cemetery in Burlington.